Contemporary Censorship in New Zealand

New Zealand might not be the first country to come to mind when considering literary censorship. But its long, ongoing tradition of highly organized censorship throws up interesting questions around responsibility, taste, and expression.

New Zealand’s first censorship law was passed in 1892. During World War I, anti-war propaganda was made illegal, with punishments including fines, imprisonment, and hard labor.

Under the country’s current classification system, a publication is declared objectionable (effectively banned) if it’s considered to promote either extreme violence or certain sexual acts: coercion, exploitation of children, bestiality, necrophilia, use of urine, or use of excrement.

Other criteria can be applied on a case-by-case basis, including age restriction in the case of “highly offensive language.” In practice these ad hoc restrictions often apply to books intended for young readers.

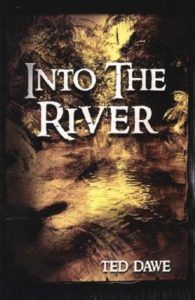

In 2015, Ted Dawe’s young adult novel Into the River was placed under an interim restriction order by the President of the Film and Literature Board of Review, which prevented its distribution until further consideration. According to PEN America, New Zealand only publishes about 20 YA novels a year, so there was no hiding this. Into the River follows a Māori boy who leaves his rural area to attend a boarding school with complicated social and sexual dynamics. A Christian advocacy group objected to these themes.

New Zealand also restricted Philip Nitschke’s The Peaceful Pill Handbook, which describes various euthanasia methods, for nearly a year, beginning in 2007. The book was criticized for discussing illegal acts. The chief censor of the Office of Film and Literature Classification ultimately allowed it to be sold to adults after certain pages were redacted.

The current chief censor, David Shanks, has called himself “the last censor in the western world.” He’s described how challenging it is to be continually exposed to violent and abusive material, and the need to be sensitive to common local concerns (such as suicide) and not necessarily the type of content that causes offense in other countries (such as profanity and nudity in the U.S.).

Shanks’s decision that has garnered the most attention was the ban on possessing or sharing the manifesto of the gunman who killed 51 people at two Christchurch mosques in March 2019. Shanks declared that this hate-spewing document went beyond (legally protected) hate speech, as it was designed to perpetuate terrorism. The New Zealand ban didn’t extend to countries such as Ukraine, where the manifesto was printed and sold.

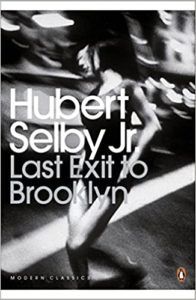

In general, the well-organized Register of Classification Decisions allows users to search restricted material. According to this database, in the last decade only a handful of books have been declared objectionable. These decisions were mostly due to sexual content involving children, although several drug handbooks have also been banned. More common are age limitations. Hubert Selby Jr.’s Last Exit to Brooklyn was restricted to 16+ (with an acknowledgment of its literary quality), while Melinda Gebbie and Alan Moore’s Lost Girls was restricted to 18+.

As for books that were complained about but failed to meet the censor’s bar for restriction: Parents with fraying nerves may be relieved to learn that Go the Fuck to Sleep was okayed.

And the censor’s description of Kate & Wills up the Aisle: A Right Royal Fairy Tale is delightfully dry: “It includes mildly sexual depictions as part of an irreverent satire…The satire degrades its subjects, but not to an extent or degree, or in a manner, that is likely to be injurious. The book’s cover bears an image of the Prince in uniform romantically crowning the Duchess, who wears lingerie…The book’s satire is likely to be offensive to some readers who are drawn to the book and expecting more conventional coverage on the British Monarchy.” The censor didn’t restrict Kate & Wills up the Aisle, but did recommend that distributors stick warning labels on it for the sake of royalty-lovers who don’t love humorous royalty-lovin’.