Why and How Censorship Thrives in American Prisons

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Censorship in prisons is the biggest First Amendment violation in America. Yet it remains one of the least talked about and least examined.

“[W]ith prisons, we’ve created an opaque system. Until recently, not many people witnessed the day-to-day activities inside of prison and thus our perceptions have been guided by the most outlying vignettes—fictional portrayals of prison life, like in Oz, or media coverage of riots and other violence. So when prison censors tell us that something is ‘necessary to maintain security,’ it’s easier to believe that security could be easily compromised and that these guards have the expertise to assess the risk correctly,” said Michelle Dillon, a representative of the Human Rights Defense Center (HRDC) and Books to Prisoners.

Paul Wright, Director of HRDC, is more direct about why there’s such tremendous censorship in prisons. “[W]e live in a fascist police state where the control of the population through armed state violence is paramount and that includes restricting the flow of ideas and writing and reading itself,”

“It is steadily increasing and this mirrors society at large with the exponential expansion literally and figuratively of the police state and the surveillance state and this ranges from the obvious (more cops, prosecutors, guards, more prisons, more jails, etc.) to the technological of having better, cheaper means to surveil, control even kill people,” he added.

As part of Banned Books Week in 2019, PEN America drafted a policy paper that goes deep into the realities of censorship in American prisons.

“It’s become increasingly clear to us how widespread and systemic this problem is, and how the national trend is towards more restrictions on the right to read, not less. We wanted to try to help re-orient the conversation—towards the necessity of upholding the right to read, and pushing back against these restrictions,” said James Tager, Deputy Director of Free Expression Policy and Research at PEN America. “One of the reasons we felt so strongly about the need for this report is to highlight how this is an issue of access to literature, not just a prison reform issue. We want readers and writers across the country to get upset about this.”

Key findings include the reality that books about race and civil rights are among the most likely to be banned; that there’s no meaningful insight into what and how books are banned (this job is often relegated to the mailroom and arbitrary decision making occurring therein); and what “content-neutral bans” are, as well as how being selective in the vendors from which incarcerated individuals can receive books further hinders access.

PEN America notes that, despite the fact those in prison can argue for their First Amendment rights—particularly when it comes to book bans and censorship—many do not because of the fear of retribution.

As more reports surface about the reality of prison censorship, and more organizations—nonprofits, newsrooms, legal, and others—step forward to advocate on behalf of the populations behind bars, more needs to be said and done about one of the biggest hindrances to change. Prison book donation policies across the U.S. vary by state, are inconsistent, and willfully create barriers that make even understanding the vastness of the problem incomprehensible.

The lack of open reporting, of open access to banned books lists, and the silence to those inside the system, as well as outside it, further harms this sensitive population who, as research continues to show, are less likely to experience recidivism when given access to books.

“This period is one of the first times when these restrictions are being examined by a wide audience; in other words, a lot of the conferred latitude has happened by simple lack of both internal and external oversight,” said Dillon.

Prison Book Censorship by State

A letter included in the book “Dear Books to Prisoners,” a compilation of letters sent from incarcerated individuals to prison book donation organizations, reads: “[It’s] the only chance of hope to escape the madness prisons are known for. I am free as I chase word by word, page by page! 500, 1000, even 2000 pages are never enough.”

Policies and Procedures Vary, are Inconsistent and Non-Transparent

Each U.S. state operates their prison systems independently, meaning that the policies about what they do and don’t allow in the mail for people who are incarcerated vary. The policies tend to be state-wide, and as outlined in the PEN America report: “[P]rison officials generally have broad latitude to ban books based on their content, including the prerogative to develop their own rationales for why a book should be blocked. They usually do so on one of several grounds:- Sexual content. nudity, or obscenity

- Depictions of violence or language perceived to encourage it

- Depictions of criminal activity or language perceived to encourage it

Authorized Distribution of Books in Prisons

Another challenge is the means by which books are allowed to reach the incarcerated. PEN calls these “content-neutral bans” and defines them as “often implemented as part of a ‘Secure Vendor’ program, by which the prison allows incarcerated people to purchase packages only from certain pre-approved vendors. Because these restrictions are based not on the content of certain books but instead aimed at restricting books-as-packages.” These, PEN states, are actually far more damaging than the blanket book bans.

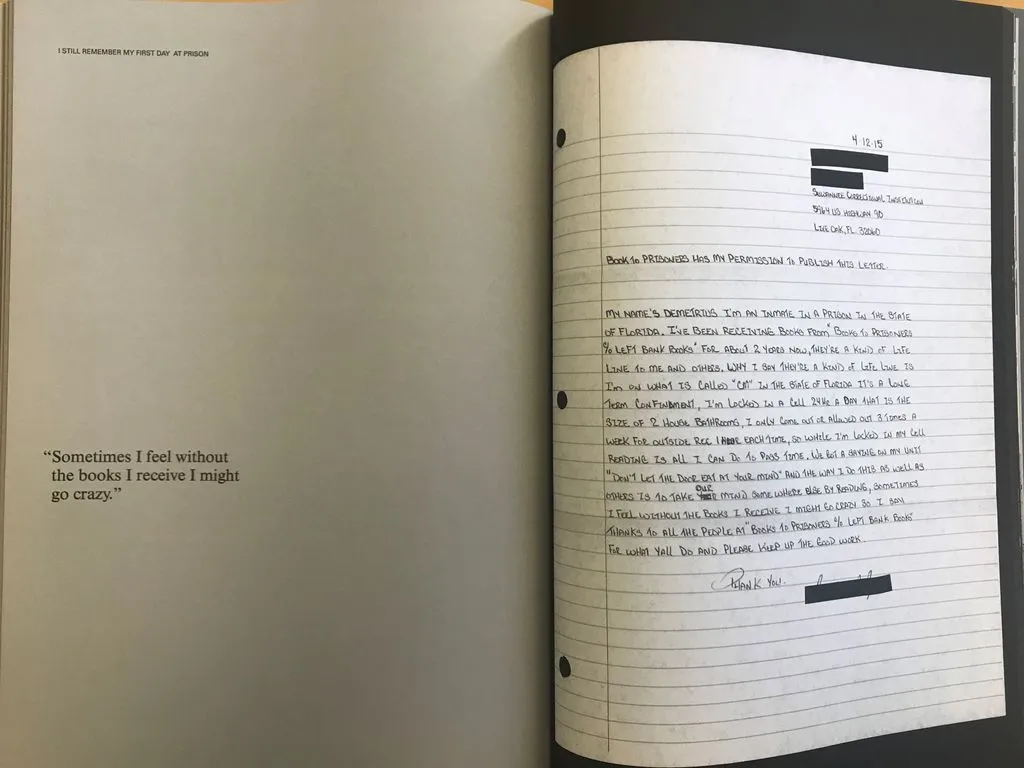

A letter published in “Dear Books to Prisoners” from Books to Prisoners. Demetrius shares what books have meant to him while incarcerated, with a pull quote on the left reading “Sometimes I feel without the books I receive I might go crazy.”

- Forcing incarcerated individuals to pay for books directly

- Being unable to receive books in the mail from friends and family

- Relying on third-party organizations like Books to Prisoners and Books Through Bars to supply books

- Permitting the incarcerated to only purchase books from specific vendors, which gives vendors a monopoly and opportunity to overcharge for their materials.

What are Prisoners Allowed To Have?: Restrictions on Material Quantity, Types

As a result of the lack of transparency about books being banned in prisons, the creators of the censored books are often unaware that their books have been restricted. Authors who write books for this population, hoping to offer them guidance, insight, education, and hope, frequently do not know their titles have been withheld, unless they seek out the banned book lists by state. Even then, with documentation inconsistent and frequently out of date, the reality of the situation can be unknown. Terri LeClercq, the author of Prison Grievances, which was banned in Kansas and Illinois until intervention, finds her book still unavailable in other state institutions. Written for those experiencing incarceration, LeClercq worked with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice while writing her book over the course of ten years. “After staff in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice reviewed my early draft and made very helpful suggestions (no censoring at all), I finally (10 years from beginning to publication) got it self-published and ready for sale. A lawyer friend here offered to buy a copy for each TDC unit. The very first book I sent to a correspondent was banned. I learned that because he said he didn’t get it. He checked the mail room, and they said it was on the banned list so they destroyed it,” she said, noting that ‘destroyed’ in this instance meant the book disappeared all together without explanation. It was not returned to her, and when she followed up, the mailroom reached out to the incarcerated correspondent, asking if he could afford the postage to return it to sender (“No one can, of course,” added LeClercq). “Having a 10-yr project, written directly for the very audience that was not allowed to get it, was a tremendous blow. I had had ups and downs in the project […] But this was the bottom of hell.” Her awareness of the situation—and her investment in helping those who are incarcerated know their rights—has led to further work on prison censorship. With the help of a student assistant, she pulled together a state-by-state list of the quantity and quality of books prisoners are allowed and where those books may be acquired.| Alabama | Prisoners are allowed to receive only 2 books per month in the mail |

| Alaska | prisoners allowed 5 books at a time, only new books |

| Arizona | Recently banned books on racism in justice system and imprisoned black men, unspecified specific restrictions on books |

| Arkansas | Unspecified restrictions on number of books per prisoner |

| California | Books must be soft-covered, prisoners allowed up to 10 books at a time, when they receive new ones they must return old ones |

| Colorado | Unspecified restrictions on number of books per prisoner |

| Connecticut | New books only, Unspecified restrictions on number of books per prisoner |

| Delaware | restrictions on size of books allowed, limits based on storage in facility |

| Florida | Limit to 4 personal books, 4 subscriptions |

| Georgia | unspecified limit on number of books |

| Hawaii | Books, magazines, food items, etc., may not be sent to an inmate |

| Idaho | Books must be soft-covered, publications can be new or used |

| Illinois | One prison recently removed 200 books on the subject of black history and empowerment, no limit of publications sent through mail, maximum of 5 publications per visit and cannot be wrapped, packaged, or otherwise contained in any way |

| Indiana | Prisoners can only receive publications from publishers |

| Iowa | All publications must be unused, sent directly from reputable publishing firm or book store |

| Kansas | Prisoners allowed up to 12 books and 10 magazines |

| Kentucky | Prisoners can receive publications from an authorized mail order distributor of published materials |

| Louisiana | Prisoners are not allowed to receive publications from family, no hard-cover books, each facility sets its own rule |

| Maine | Publications must be sent directly from publisher |

| Maryland | Prisoners are allowed 1.5 cubic feet of books and papers |

| Massachusetts | Publications must be sent directly from publisher, book club, book store, or through Prison book Program |

| Michigan | Publications must be new and sent through approved Internet vendor or publisher |

| Minnesota | Publications must be shipped through publisher |

| Mississippi | Paperbacks only, limited to 3 per month, subscriptions and newspapers sent from publisher, distributor, or vendor |

| Missouri | Limit of 6 books per package |

| Montana | Books must be soft-cover, limit of books depends on prisoner classification |

| Nebraska | Publications must be sent directly from publisher or bookstore with paid receipt |

| Nevada | New and soft-cover only |

| New Hampshire | Publications must be sent directly from publisher |

| New Jersey | Limit of 12 books, publications must be sent through publisher |

| New Mexico | Soft-cover books only; 3 books, 3 magazines, 2 religious books |

| New York | Publications should be sent through publisher |

| North Carolina | Publication restrictions based on security level of facility, pre-approved publications only, Minimum Custody: any reading material from any source; Medium or Close Custody: reasonable number directly from publisher or distributor; prisoners in a control status that prevents it cannot receive any publications |

| North Dakota | No used or previously read materials will be allowed to be sent |

| Ohio | Publications must be sent directly from publisher, a package must be limited to 1 box that does not exceed 30 pounds, box size must not exceed 12″ x 24″ x 28″ |

| Oklahoma | Publications must be sent directly from publisher, books preferably new, no specified limit to number of books |

| Oregon | Publications must be sent directly from publisher or distributor |

| Pennsylvania | Publications should be sent through publisher |

| Rhode Island | All packages must be delivered by USPS, only new paperback books |

| South Carolina | Up to 5 pages per envelope, prisoners in intake status or restricted housing are not allowed to receive publications, publications must be sent through publisher and paid for beforehand |

| South Dakota | Publications must be sent through publisher, limited to 5 small newspaper clippings and up to 10 extra sheets of paper |

| Tennessee | Publications must be sent through publisher |

| Texas | Publications must be sent through publisher, limited to space prisoner has |

| Utah | Books may only be purchased through prison commissary |

| Vermont | Soft-cover books only, prisoners can make requests to a supervisor or caseworker, publications must be sent through publisher |

| Virginia | Books larger than 11 inches by 14 inches are not allowed, Publications must be sent through publisher |

| Washington | Publications must be sent through publisher, only new paperback books |

| West Virginia | Publications must be sent through publisher, only new books |

| Wisconsin | Prisoners are allowed up to 25 publications at a time |

| Wyoming | Publications must be sent through publisher, hardback books and other publications are not allowed |

What Can Be Done?

“I put together a list of books I wanted and wrote letters to hundreds of organizations and famous people I read about in magazines asking if they would donate one of those books to the Patuxent library. Can you imagine how special that was to hear the library got a new book and realize it was one I asked for, and that someone donated it because of me?“I didn’t just live for that library. I lived because of that library. The Patuxent prison library saved me from crushing despair. It saved hundreds of other guys, too.”—Chris Wilson, formerly incarcerated author Because of better tools of communication, connection, and time, awareness of the depths of prison censorship is growing. This means that, thanks to the work of advocacy groups, on-going legal challenges, and reports like those done by PEN and similar groups and individuals, more information exists. And this information means that the average citizen can get a better handle on how they can act and stand up for the rights of those experiencing incarceration. “In my capacity with Books to Prisoners, we do this work for several reasons. Many of us are librarians, book store employees, and other pro-book people; we want to see the joy of reading spread as far as possible. We also do this because—especially as we work with these groups longer—we see the profound isolation and deprivation experienced by people in prisons and we want to remedy that in even this very small way. There are a variety of perspectives in books to prisoners programs, from those who see this as prisoner support and abolition work, to those who operate from the framework of rehabilitation and want to see prisoners gain access to tools for job training and higher education in order to “better themselves” and decrease recidivism,” said Dillon. She noted that the most commonly requested books include dictionaries, Spanish language learning, black history and fiction, how-to-draw, manga & comics, vocational training (including plumbing, etc., as well as how to start a business), genre fiction (fantasy, sci-fi, thrillers, and horror in particular), ancient history, mythology, occult, legal self-help, and games (sudoku, crosswords, D&D). What’s the average person to do? In what ways can the work continue to push forward?

Know Who Is In Charge of Prison Oversight In Your State

Step one is getting to know who is in charge of prison oversight and speaking up against these behaviors on a state level. “[T]hese actions and abuses continue because we continue electing politicians who endorse or appoint the people who do them. Governors are responsible for the prisons, sheriffs generally for the jails. If there is a political price to pay these practices may stop. […] it doesn’t take a huge amount of support or outcry to get prisoncrats or jail officials to back down on small limited issues. The reality is we have a police state with little in the way of accountability or transparency at any level, not just around censorship,” said Wright. Likewise, understand what the policies are within your state when it comes to book censorship. Reach out to your state’s DOC and ask for them. Ask about policies and procedures, as well as lists of titles and reasons. As noted, the chances of receiving an answer easily are slim to none; but collective action and effort move the needle. One way to make this process a little easier is to develop a series of email templates asking for information that can be copy and pasted. Keep those, as well as all correspondence, in a file for record keeping. As Wright notes, understand your state governor’s stance on prison oversight. Again, write letters. Know what policies local and state-level sheriffs follow and know the chain of command—who does the sheriff report to? That’s who to write to when answers don’t come back and/or you want to know more and are seeing nothing from the sheriff. We’ve seen the power of elections and the necessity in voting. This is not just true on the national level. In many ways, those state and local elections are equally, if not more, imperative.Donate (Time/Talent/Money) to Organizations Doing The Work

Dillon emphasizes that the fight begins locally. “The average citizen can start by connecting with a local prison book program, higher ed in prison, or other prison advocacy group, if there is one in your area. If there’s a prison book program that you can join, help answer requests for books; learn firsthand about the difficulties of providing books—the arbitrary returns, the proactive self-censorship to try to avoid assumed restrictions, the dedication of other activists. Use that community as a potential launching point to collaborate on a statewide campaign if you find that one is necessary (for example, we’re having issues with overall book access in Indiana and Michigan right now, and nearly every state could use a push to create better publication review committees and publicly available lists of censored materials).” Whatever talents you have, those can be put to use in protecting the First Amendment rights of people in prisons. “[A]re you a great graphic designer? Do you know state politicians who might be interested in talking about these issues? Can you write persuasive letters? This is a community fight, so find your community first,” Dillon added. Organizations like the HRDC are great places to donate money, particularly as they have long and successful track records of litigation. Their work has a traceable paper trail and leads to changes as seen in states like Washington. Snow says, “There are a couple dozen programs like ours across the country, all powered by donations and volunteers. I recommend this volunteering to anyone. The letters we get can be thoughtful, funny, or a small delight when someone asks for a book by your favorite author that you can fill, and the notes we get back are wonderful. Even if you don’t live near one of these groups to volunteer your time or drop off books, buying books from wishlists like ours is something that keeps us going.” “[T]here is something free that interested people can do: keep an eye on their state’s rules around sending books to prisons. Many states are trying to restrict packages just from vendors like Amazon, or even going to tablets that force inmates to buy the expensive technology and books that can be marked way up, even books in the public domain. We have had success pushing back, most recently in Maryland, but it will be an ongoing fight that people can help by contacting their representatives and Governors to let them know they don’t agree with policies like these,” added Snow.Be The Voice

“Public outrage has been instrumental in reversing recent policies across the country. It’s vitally important to help demonstrate to prison officials that the American people do not support overbroad and arbitrary restrictions on literature, or policies that severely limit access to books. Overall, people should absolutely be speaking with their elected officials about this,” says Trager. He adds that local reporters played a significant role in uncovering book bans and bringing them to the attention of the public—the endnotes of the PEN America report highlight the value that local media outlets have in making these acts of censorship known. “This is a story that is often first uncovered at a local level, sometimes well before it reaches more national attention,” he adds. When the realities of prison censorship come to light, it’s too easy for those without the knowledge or understanding of the depths of the problem to make light of the situation. But it’s not joke. Certainly, books can be weapons and can be tools used for transporting illegal substances into prisons. But these instances are exceptionally uncommon. What’s far more common is for the First Amendment rights of the incarcerated to be denied. It’s been proven that access to books reduces recidivism. People make mistakes and commit crime. They serve the punishment given to them by a judge and/or a jury. During this time, they have an opportunity to better themselves in whatever ways necessary so they’re prepared for life on the outside again, be it in six months, six years, or sixty years. For vulnerable populations within an already-vulnerable population—black men and women experiencing incarceration in particular—having access to materials about the prison system, racial justice, and their rights is crucial. Already unjustly targeted, they face further challenges in and out of the school-to-prison pipeline, due to bigotry, racism, classism, and denial of tools for rehabilitation. Listen to those in this community and rally in support of their rights. Trager adds, “We need to shine a light on how useful, inspiring, and dignity-enhancing book access is for those who are incarcerated. Pragmatically, access to literature has been shown to help reduce recidivism rates. But we need better protections to support the right to read and access to books in prisons. We need more meaningful review mechanisms, more transparent and clearly-defined rules over what constitutes grounds to ban a book, more consistent application of these rules from prison officials. We need a standard of review that recognizes and values the literary merit of a challenged book, training and regulations that explicitly incorporate First Amendment principles and affirms the basic right to read…all of these represent steps we should take to help ensure that the urge to censor is not running rampant in our prisons.”Further Reading

If you want to know more and go deeper, there is a range of incredible material available. Here’s a small selection of outstanding reading:- PEN America: Literature Locked Up report

- Censorship in Prisons and Jails: A War on the Written Word by Christopher Zoukis

- Why are books banned in prisons? by Terri LeClercq and Joanne Sweeny