Celebrating Pride and Queer Lit with HIDE

Hide is something special. A book about love that doesn’t take as its leads young star-crossed lovers, but two elderly men – Wendell Wilson, a taxidermist, and Frank Clifton, a World War II veteran. Through flashbacks we learn about how they fell in love, in a time when being gay was not accepted and could even be dangerous. This necessity of secrecy shapes their lives together. They are forced to put their love and desire before family, friends and opportunity.

Griffin captures the complexities of a relationship shared over decades, nurtured and hidden away from the hostility of society. We meet the characters in the midst of a tragedy. Wendell finds Frank collapsed in the garden, and through the book nurses him through his encroaching dementia. I felt Wendell’s frustration at Frank’s increasingly erratic behaviour, and shared the small joys of recollected past experiences and moments of lucidity. Their love is strange – to quote the title of the wonderful John Lithgow and Alfred Molina film that also touchingly addresses elderly love – and it is the difficult nature of the relationship that is so moving, fascinating and ultimately human.

Griffin captures the complexities of a relationship shared over decades, nurtured and hidden away from the hostility of society. We meet the characters in the midst of a tragedy. Wendell finds Frank collapsed in the garden, and through the book nurses him through his encroaching dementia. I felt Wendell’s frustration at Frank’s increasingly erratic behaviour, and shared the small joys of recollected past experiences and moments of lucidity. Their love is strange – to quote the title of the wonderful John Lithgow and Alfred Molina film that also touchingly addresses elderly love – and it is the difficult nature of the relationship that is so moving, fascinating and ultimately human.

Although there has been some progress since the post-war period, we can still do more to address past and present wrongs. I’m sure we would all like to think we live in a just, fair and equal community. But, there are many places where homosexuality is still ostracised, even persecuted. There have been some really worrying reports about gay purges in Chechnya recently.

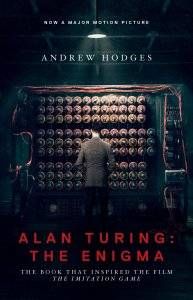

Even in the UK, according to Peter Tatchell, it was only in 2003 that all homophobic sexual offences legislation was repealed, and it has taken until this year for ‘Turing’s Law’ to be passed. (Named after Alan Turing, the genius mathematician who killed himself after being convicted of gross indecency.) The law allows for the posthumous pardoning of those wrongly criminalised for their sexual orientation. However, the language it is couched in suggests that people are being forgiven for past wrong doings, when actually it is the system and legislators who should be apologising for persecuting innocent men and women. To make it worse, if you have been convicted of one of these now redundant crimes and are still alive, you have to actively request a ‘disregard’. This again takes away the responsibility from the state and places it on those who have been wrongly maltreated. As I said, we are moving in the right the direction, but we have further to go.

Even in the UK, according to Peter Tatchell, it was only in 2003 that all homophobic sexual offences legislation was repealed, and it has taken until this year for ‘Turing’s Law’ to be passed. (Named after Alan Turing, the genius mathematician who killed himself after being convicted of gross indecency.) The law allows for the posthumous pardoning of those wrongly criminalised for their sexual orientation. However, the language it is couched in suggests that people are being forgiven for past wrong doings, when actually it is the system and legislators who should be apologising for persecuting innocent men and women. To make it worse, if you have been convicted of one of these now redundant crimes and are still alive, you have to actively request a ‘disregard’. This again takes away the responsibility from the state and places it on those who have been wrongly maltreated. As I said, we are moving in the right the direction, but we have further to go.

As avid readers, we are lucky that we have access to books giving us insight into different lives, different perspectives. But, we should do more to put these types of voices centre stage. This is why I think Hide is important: unless we are told stories of rich, complex humanity, it is very easy to slip back into stereotype and a reductive understanding of others. I hate to repeat aphorisms, but history is written by the winners. We still see this in how the media and culture is dominated by white, heterosexual voices. They may be benign and engaged, but are still talking from the centre. Let’s make our fiction as diverse as ourselves.