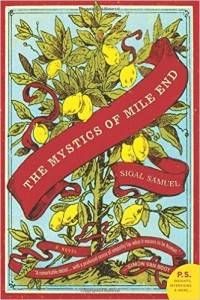

Catching Up with Author Sigal Samuel

Sigal Samuel is an award-winning fiction writer, journalist, essayist, and playwright. Currently opinion editor at the Forward, she has also published work in the Daily Beast, the Rumpus, BuzzFeed, and Electric Literature. She has appeared on NPR, BBC, and Huffington Post Live. Her six plays have been produced in theaters from Vancouver to New York. Sigal earned her MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia. Originally from Montreal, she now lives and writes in Brooklyn. The Mystics of Mile End is her first novel.

Rachel Cordasco: Favorite writers? Favorite books?

Sigal Samuel: My favorite dead writer is Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who wrote Brothers Karamazov. My favorite living writer is Nicole Krauss, who wrote The History of Love. Which sometimes leads me to wonder: What sort of person would you get if you combined the two? And what sort of book would that person write? I don’t know, but it would probably be depressing as hell, in the most beautiful way possible.

RC: How has growing up in Canada and living in the U.S. informed your writing/general worldview?

SS: I grew up in Canada reading a lot of American books, and they always made it seem like the entire universe consisted of a few blocks in Brooklyn’s Park Slope plus a few blocks in Manhattan’s Upper West Side. When I wrote the first draft of my novel, I unselfconsciously set it in Montreal. By the time I sat down to write the second draft, I had moved to Brooklyn and was wondering whether I should move the whole story down here, too. Would that make my novel more marketable? Easier for American readers to relate to? Ultimately I decided that the world has enough Brooklyn books, and that I would trust readers to take an interest in something beyond their immediate surroundings. They haven’t let me down.

RC: I’m loving your debut novel, The Mystics of Mile End. What was the genesis of the book and how did that change as you wrote?

SS: My dad was a professor of Jewish mysticism and he taught me Kabbalah starting at a very young age. So I always knew I wanted to make use of those texts and ideas in a novel. (Or, to put it more accurately, I couldn’t not use them — telling me not to write about mystics would’ve been like telling me not to breathe oxygen.) I wanted to take these medieval religious ideas and bring them into a contemporary, secular, urban setting, so that I could explore the question: What would happen if someone like you or me tried to climb the Kabbalah’s Tree of Life as a way to reach God, right now, in 2015?

I turned to J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey often while writing, because I think he’s asking a similar question in that book, which is one of my favorites. But whereas Salinger uses two voices to tell his story, I found I needed a few more. I wanted to show a dysfunctional Jewish family falling under the sway of a dangerous mystical obsession, with each person getting the chance to tell their side of the story. Here are the four perspectives I ended up with: an endearingly nerdy little boy, an atheist middle-aged professor, a female college student who’s losing her mind, and the Montreal neighborhood they all live in — Mile End — which is home to hipsters and Hasidic Jews.

RC: How does working as an editor and writer at the Forward influence your fiction-writing and vice versa (or at all)?

SS: Working as a newspaper editor has cured me of the tendency to get too attached to my own passages, even (or especially) when they’re long meandering paragraphs full of very pretty sentences that don’t advance the plot. I used to find it impossible to cut those paragraphs. Now I’m so practiced at hacking away at other writers’ work that I know better than to protest “but I couldn’t possibly shorten that, this part simply can’t be cut!” An editor needs me to chop 10,000 words out of my book? I say, sure, no problem.

Caveat: In every book there will be at least one passage that you will fight to the death to keep. That’s good. Mine is on page 130.

RC: What advice would you give to aspiring authors?

SS: If you don’t see characters like yourself or your relatives represented in books, don’t assume that means you can’t write about such people. Assume the opposite! Why not write exactly those kinds of people? Instead of aiming for some mythic “neutral universal” (to borrow a phrase from Zadie Smith), trust that you will get at the universal through the particular.

RC: What’s your favorite Yiddish-ism?

SS: My favorite Yiddish-ism is “Verter zol men vegn un nit tseyln,” which means: Words should be weighted, not counted. The characters in my novel are all terrible communicators, and they’re constantly hoarding language, counting out each precious phrase they expend, as if they believe we’re each born with a finite stash of words inside us and as soon as we use them all up we’ll die. Actually, one of my characters believes that literally. I always want to tell him: Yes, by all means, weigh your words, consider them carefully, but don’t be so goddamn miserly!

Since my own Jewish family doesn’t actually come from Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europe — instead, we’re from India, Iraq and Morocco — I can’t leave without also giving you one of my favorite Arabic-isms. “Bukra fil mishmish” is an expression that literally translates to “tomorrow morning, you can have apricots.” Thing is, you can never really enjoy apricots the day after you pick them, because they turn to mush too fast. So when you say this phrase to someone, you’re sarcastically telling them: It ain’t gonna happen. Or, as a Brooklynite might say: Fuhgeddaboutit.