The History of the Bury Your Gays Trope

What is the Bury Your Gays trope? It’s a trope used in media in which a queer person, often in a romantic relationship, tragically dies. The trope isn’t just about death and loss, however, but is often used to undermine queer people and relationships. The tragic death often occurs just after a first kiss or sexual experience. It can also occur just before that magical moment in which a person fully embraces their queerness. In this way, it becomes a form of queerbaiting and portrays LGBTQIA+ people as disposable.

When there’s a potential romantic relationship, there’s another side to this terrible loss. Too often, part of the Bury Your Gays trope is the surviving partner having some sort of realization that they were never queer at all. They may return to a heterosexual partner in order to get their “happily ever after.” Though that just sounds like the prelude to any tragic Tennessee Williams play.

So how did this trope start? How has it progressed over time?

Early Bury Your Gays

Long before the trope was given a name, Bury Your Gays first appeared in the late 19th century. While still abhorrent, the trope actually has somewhat uplifting roots. Imagine that it’s the 1890s. Or 1920s. Or 1960s. You’re an LGBTQIA+ (another term that didn’t exist then) writer, and you want to write a romantic relationship that actually reflects your (likely closeted and closely guarded) experiences.

The Criminal Amendment Act of 1885 in the United Kingdom outlawed “committing acts of gross indecency with male persons.” According to psychiatric professionals, homosexuality was a form of insanity. Similarly, if you were writing during McCarthyism, you could be labeled a Communist and blackballed if you were suspected of being gay. The Hayes Code didn’t allow homosexual relationships to be depicted in films. Good luck finding a mainstream publisher willing to put your story into print.

But what if you never actually confirm the homosexual relationship?

That’s where Bury Your Gays gets its start. Take away the hand-holding, the kissing, certainly any sex scenes, and you could have a queer-coded relationship on the screen that tragically ends before there is any confirmation.

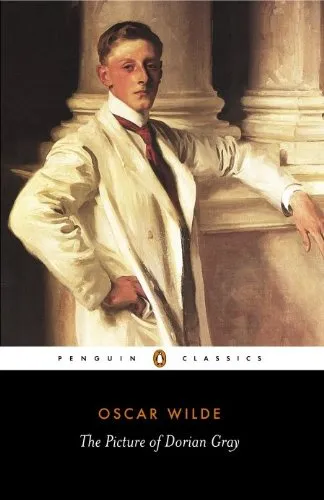

Sounds ridiculous, but just look at how many historians refuse to look at historical figures through a queer lens, instead just calling people “good friends.” It’s certainly better than being jailed like Oscar Wilde, who himself used the trope in The Picture of Dorian Gray.

The history of lesbian pulp fiction is filled with this trope to avoid censors and various obscenity laws. If a LGBTQIA+ character was giving a happy ending under these laws, the story was considered to be promoting homosexuality, but kill one off at the end and it’s a cautionary tale.

So Gay People Cannot Die in Narratives?

This is the common pushback to the overuse of the Bury Your Gays trope. Just because a character is queer doesn’t mean that they must survive the narrative to avoid the trope. For example, in Jonathan Larson’s RENT, most of the characters are queer, and most have AIDS. Angel even dies during the story.

However, Angel’s queerness is openly addressed and admired. Their relationship with Collins is on full display and is loving. Taking place during the AIDS epidemic, the dizzying loss of life in the LGBTQIA+ community is a vital part of that story, so the story ending without a gay character dying would have felt disingenuous. Even though Mimi (a straight woman) magically survives her own brush with AIDS-related death at the end, we know based on the disease and the time period that it is only a temporary reprieve. Furthermore, the number of queer characters in RENT undermines the trope. Bury Your Gays often targets the only — or one of the only two — queer characters in a story.

The main difference between LGBTQIA+ characters dying versus fulfilling the Bury Your Gays trope is what it says about LGBTQIA+ characters. The trope says that they are disposable, that they cannot live happily ever after while their hetero counterparts do. They must die because they are queer.

Modern Examples of Bury Your Gays

Sadly, over a century since the passing of the Criminal Amendment Act of 1885, the Bury Your Gays trope is still alive and well. In CW’s 2014 series, The 100, Lexa dies almost immediately after getting together with Clarke. In Supernatural, Charlie (basically the only queer character in the show) is brutally murdered. Killing Eve, Orange is the New Black, and The Walking Dead have all used the trope.

On the book side of things, George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire books never let their queer characters have happy endings, often killing them in terrible ways before they ever find happiness. Taylor Jenkins Reid’s The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo and Philip Pullman’s The Amber Spyglass both include the Bury Your Gays trope.

At least today, with growing support for LGBTQIA+ people and communities, there are also many great examples of queer representation in film and books. From shows like Yellowjackets and She-Ra: Princesses of Power to the myriad queer books with happy endings, these works portray those elusive happily ever afters (or at least, happy so far) for LGBTQIA+ characters. They don’t queer code, but fully depict queer people and queer relationships. These works fly in the face of hateful commenters and tell the stories that need to be told.

Now let’s just bury the Bury Your Gays trope and move boldly forward into our queer future, shall we?

If you liked this post, you might also be interested in reading The Unique Relationship Between Queer Media and Spoilers and Do Queer Books Still Need Happy Endings?