Books We “Like”: Uncollected Thoughts on Facebook and Reading

I don’t think I was alone in finding myself perturbed when Facebook changed the look of its “Arts and Entertainment section” earlier this year. For a long time I had been developing an interest in the books Facebookers choose to list on their profiles and I found that Facebook’s change from a simple dignified list of “favorite books” to gaudy pictures of book covers to be horrible on both aesthetic and clerical grounds. In a certain sense, however, Facebook’s new system of literary taxonomy makes detecting trends in the book preferences of its users (i.e., of all of us) a little easier. In forcing its users to list just five or less books prominently on their profile, with the option to list many more that the potential viewer can see upon clicking the conspicuously labeled “more” tab, Facebook is giving us a good picture of what our friends would like to be thought of as having read by at least forcing them to narrow down the top tier. The results are sometimes peculiar. The following is an anecdotal list of oft chosen “top tier” picks, rather than an empirical one.

The Bible: Many Christian Facebookers say their favorite book is The Bible. These profiles generally also “like” (also sometimes listed as a book, which is even more peculiar) “The Constitution.” But what does it mean to “like” “The Bible” alongside determinately secular entities like Wilco and Ron Paul? Even the basic premise that The Bible is a “book” that can be regarded as such amongst others is anachronistic and secularizing on some level (devout Catholics in the house?). Although there are many books within “The Bible,” the idea that the bible as such constitutes a book is distinctly modern. The Bible wasn’t really a “book” as such until the 16th century, and even then hardly a book among books. But let’s not give our Christian brothers and sisters any grief. “The Bible” is in my humble estimation the best read of the commonly “liked” books listed herein. We can all mostly agree that the compendium of ancient Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic Mediterranean literature, whose English translation is today “The Bible,” contains incidences of supreme literary and conceptual beauty, wherever its inspiration resides. Our list of ever-present favorite books on Facebook doesn’t get truly revealing until it gets a bit more contemporary…

The Bible: Many Christian Facebookers say their favorite book is The Bible. These profiles generally also “like” (also sometimes listed as a book, which is even more peculiar) “The Constitution.” But what does it mean to “like” “The Bible” alongside determinately secular entities like Wilco and Ron Paul? Even the basic premise that The Bible is a “book” that can be regarded as such amongst others is anachronistic and secularizing on some level (devout Catholics in the house?). Although there are many books within “The Bible,” the idea that the bible as such constitutes a book is distinctly modern. The Bible wasn’t really a “book” as such until the 16th century, and even then hardly a book among books. But let’s not give our Christian brothers and sisters any grief. “The Bible” is in my humble estimation the best read of the commonly “liked” books listed herein. We can all mostly agree that the compendium of ancient Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic Mediterranean literature, whose English translation is today “The Bible,” contains incidences of supreme literary and conceptual beauty, wherever its inspiration resides. Our list of ever-present favorite books on Facebook doesn’t get truly revealing until it gets a bit more contemporary…

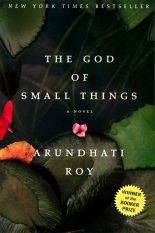

Arundhati Roy—The God of Small Things: This leftist firebrand’s first and only novel shows up on the “favorite books” list of late teens and early twenty somethings with surprising ubiquity. Or, maybe it isn’t so surprising? While conservatives prefer the God of Big Things, liberals….well…you get the idea. This debut novel is full of lyrical passages, sometimes exquisite and searing, chronicling the lives of two fraternal twins of upper-caste families in the Indian town of Aymanam. The two protagonists, and a few ancillary characters at that, struggle throughout to achieve loves that transcend racial, caste, and religious boundaries—(in one memorable case, an older sister is captivated by her love for an Irish Catholic priest who has come to Aymanam to study Hindu scripture: Father Mulligan). The book too is in the opinion of the present writer also something of a mulligan. There is nothing particularly wrong with this novel. I recall myself finding it in places beautiful and hard to put down, but ultimately its singular focus on “who must be loved, and how, and how much” becomes overly rhetorical and moralistic, which might be why its author went on to make a career in rhetoric. “Likers” of The God of Small Things also tend to like Vladimir Nabokov (which is weird, because his work suffers from precisely the opposite problem), Amnesty International, and rock fusion groups like Broken Social Scene and Animal Collective. Go figure.

Arundhati Roy—The God of Small Things: This leftist firebrand’s first and only novel shows up on the “favorite books” list of late teens and early twenty somethings with surprising ubiquity. Or, maybe it isn’t so surprising? While conservatives prefer the God of Big Things, liberals….well…you get the idea. This debut novel is full of lyrical passages, sometimes exquisite and searing, chronicling the lives of two fraternal twins of upper-caste families in the Indian town of Aymanam. The two protagonists, and a few ancillary characters at that, struggle throughout to achieve loves that transcend racial, caste, and religious boundaries—(in one memorable case, an older sister is captivated by her love for an Irish Catholic priest who has come to Aymanam to study Hindu scripture: Father Mulligan). The book too is in the opinion of the present writer also something of a mulligan. There is nothing particularly wrong with this novel. I recall myself finding it in places beautiful and hard to put down, but ultimately its singular focus on “who must be loved, and how, and how much” becomes overly rhetorical and moralistic, which might be why its author went on to make a career in rhetoric. “Likers” of The God of Small Things also tend to like Vladimir Nabokov (which is weird, because his work suffers from precisely the opposite problem), Amnesty International, and rock fusion groups like Broken Social Scene and Animal Collective. Go figure.

J.D. Salinger—Franny and Zooey. While it might be a bit pedestrian to list oneself as a “liker” of JD Salinger’s classic novel of that singular hatred for hypocrisy that is the youth of any truly precocious boy Catcher and the Rye, not so when it comes to his intertwined novellas Franny and Zooey. Although read as a single novel today, either piece was published separately in The New Yorker (respectively, in 1955 and 1957). In the two stories, the basic theme of childhood as a process of acclimating oneself to the world of adults and their inauthenticity is again explored, but this time also in a feminine context (see also: Heidegger’s Being and Time). Salinger’s girls are not hysterics, and they are just as struck by the deafening and hypocrisy of the word as his boys. “Likers” of Franny and Zooey like many of the same things that those who like Ms. Roy’s novel appreciate, with more emphasis on cats.

J.D. Salinger—Franny and Zooey. While it might be a bit pedestrian to list oneself as a “liker” of JD Salinger’s classic novel of that singular hatred for hypocrisy that is the youth of any truly precocious boy Catcher and the Rye, not so when it comes to his intertwined novellas Franny and Zooey. Although read as a single novel today, either piece was published separately in The New Yorker (respectively, in 1955 and 1957). In the two stories, the basic theme of childhood as a process of acclimating oneself to the world of adults and their inauthenticity is again explored, but this time also in a feminine context (see also: Heidegger’s Being and Time). Salinger’s girls are not hysterics, and they are just as struck by the deafening and hypocrisy of the word as his boys. “Likers” of Franny and Zooey like many of the same things that those who like Ms. Roy’s novel appreciate, with more emphasis on cats.

Anything by Kurt Vonnegut: I know this was promised as a list of those books that are most commonly listed on Facebook, not their authors. But anyone who has ever known a true Kurt Vonnegut fanatic knows that, somewhat uniquely amongst this species within the broader book geek flora and fauna, Vonnegut nuts judge one another not in terms of which Vonnegut book their cohorts privilege above all others but in terms of a singular question, almost a singular piety: “how many Vonnegut books have you read?” To put it out there in the open, the present writer has read God Bless You Mr. Rosewater, Cat’s Cradle, and Mother Night, which on a Vonnegut fan-boy scale of 1-10, puts me at about 0.5 (and yes, I am writing a paragraph about Vonnegut without having read Slaughterhouse Five, send your cultural taste mongering cartel after me if it makes you feel better). There are really two kinds of Vonnegut readers, those like myself, who after a few very enjoyable rides in our late teens, get the idea and move on, and…Vonnegut fans. Kurt Vonnegut’s most powerful insight is that modern world is already science fiction. If sufficiently de-familiarized, we can come to see ourselves not as approaching a horrid morally topsy turvy dystopia, but as already residing within one. In Mother Night, the tension is rendered ad-absurdum, with Jack Cambell, who sends coded messages to American intelligence in the form of anti-Semitic screeds for a radio program within the heart of the Third Reich. In Hegel’s terms, the question here is obvious, if the content of our actions is completely good, can it absolve us from a form that is utterly evil? For Vonnegut the answer seems to be….as his protagonist faces immanent execution by an Israeli court…”you are who you pretend to be,” which always seemed to me to be a way of solving a brilliant allegory with a catechism. Alas, this is what bothered me about the others too, which is why, before Facebook switched over to its new visual format, I could not list myself as a lover of “Anything by Kurt Vonnegut.” Vonnegut fans also seem to be over represented in the ranks of Mets fans. Go Figure.

J.K. Rowling–Harry Potter. Alas, no list of popular books is complete without The Boy Who Lived (Henceforth, TBWL). Don’t snub your nose, however, nose snubber. Rowling’s brilliant insight was that the most fanciful wish of any child, to possess magical powers and dwell within a fairy tale, could be effectively combined with that most familiar and universal setting of adolescence, school. Add a dash of the most universal feelings of adolescence to the escapist cauldron, feelings of abandonment, intense friendship, discovery of sexual love, and the addictive synthesis would transform any nay-sayer into a believer in TBWL like a bottle of polly juice potion—(but in the reverse sense, because many were transformed on the inside while remaining militantly snobbish without, ((one more example of why Vonnegut is wrong, and Sigmund Freud is right, you are precisely not who you pretend to be)). Since “likers” of Harry Potter are everyone, its difficult to typify the pages that come with them: we’re talking everything from Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic” to “Glee”, to…”The Bible.”

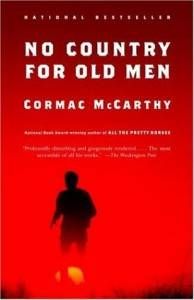

Cormac McCarthy—No Country for Old Men. If you are a man in your twenties or early thirties, with even remote interest in the higher tastes of American letters and American whiskey, then chances are you have brushed up against this man’s name alongside the words Blood and Meridian. That work, like all of McCarthy’s most stupendous creations, can only be read as a work of theology, a meditation on inner recesses of violence, the very “the darkness over the deep” that preceded God’s creation of the world and seems to always threaten to consume what little light he offered. No Country for Old Men, McCarthy’s first work to be set on the modern Texas Mexico border, is a brilliant novel that was adapted into an (arguably) even more brilliant film directed by the Coen Brothers. The most memorable character, played by Javier Bardem in the film, is the psychopathic fatalist Anton Chigurh. Interest in this mid-tier novel of one of our greatest living writers, which is to say, this great novel, was probably generated by the film’s success, but who can be upset with that? “Likers” of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men do not seem too into malt whiskey, however, which leads me to believe they have yet read Blood Meridian.

Cormac McCarthy—No Country for Old Men. If you are a man in your twenties or early thirties, with even remote interest in the higher tastes of American letters and American whiskey, then chances are you have brushed up against this man’s name alongside the words Blood and Meridian. That work, like all of McCarthy’s most stupendous creations, can only be read as a work of theology, a meditation on inner recesses of violence, the very “the darkness over the deep” that preceded God’s creation of the world and seems to always threaten to consume what little light he offered. No Country for Old Men, McCarthy’s first work to be set on the modern Texas Mexico border, is a brilliant novel that was adapted into an (arguably) even more brilliant film directed by the Coen Brothers. The most memorable character, played by Javier Bardem in the film, is the psychopathic fatalist Anton Chigurh. Interest in this mid-tier novel of one of our greatest living writers, which is to say, this great novel, was probably generated by the film’s success, but who can be upset with that? “Likers” of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men do not seem too into malt whiskey, however, which leads me to believe they have yet read Blood Meridian.

Nothing—Sad but true, our list must end with the most common form of book listing on Facebook, that of listing no books at all…Nothing…nada…zilch. It would be easy to let the language of decline to run riot and lament a world where superfluous web browsing and video gaming has taken the place of reading. If only this were true. Humanity, on par, is more literate and spends more time reading today than ever before. (Nearly) Universal literacy is an achievement of the 20th century, and the necessity of at least remedial writing skills for participation in many forms of human social interaction (read: the internet) is an emerging reality only of the 21st. While the act of reading and writing is more omnipresent in human culture, what is being blurred is the distinction between the great authors and the notes we write in the margins of their books. Those margin notes are now online comments, and in many cases can be posed directly to the authors themselves as easily as their works can be posed to us. This doesn’t mean that the nothingness that envelopes many book-lists on Facebook leaves no cause for concern about the future of literature, but any philosopher knows that there is more to say about nothingness than the absence that meets the eye.

So, in that spirit, what do you all think of the present state of reading? What books have you “liked” on Facebook?