No, Books Should Not Have Content Ratings Like Movies

One of the great joys of my young life was reading books pitched to older children. Graduating from picture books to chapter books with pictures, then chapter books, then longer and longer books was a big deal to me. For kids’ books in the U.S., you can usually find an age range somewhere on the flap or back cover of a book. Readers and people acquiring books for readers occasionally use this as a guide for getting books for appropriate ages. In recent years, certain groups have demanded a more robust rating system for books, similar to the MPAA rating system for movies. However, there are many reasons why books should not have content ratings like movies.

The general idea behind a “rating” system for kids’ books makes sense to me. The widespread availability of the Internet means that kids have access to some of the worst information ever documented with just a few keystrokes. Technology companies attempt to keep up with this freedom by providing methods of blocking content that could be upsetting or out-of-age-range for young children. The problem with books is that there’s no way to automatically censor content in books unless you ban them, rip out specific pages, or cross out certain words with a permanent marker.

Since books are longer and more involved than movies, they’re trickier to pin down with exact content ratings. Including age ranges can sort of help, but they don’t tell you much about the content. A 10 year old is also unlikely to have the exact same experiences or sensitivities as a 10 year old from a different country, or even one from a different neighborhood.

How Do Rating Systems Work?

Rating systems serve to place various types of media into understandable buckets. In the world of print media, the Comics Code Authority ruled the comics world with an iron fist for many years. Comics without the CCA stamp would not be stocked in stores — it was a symbol to parents that these comics were safe. The designation fizzled out eventually.

For films, the first major attempt to reign in saucy or shocking content was the Motion Picture Production Code (commonly known as the Hays Code), which most movie studios adhered to from 1934 to 1968. In 1968, the Motion Picture Association of America took over movie ratings guidance. They started with G (general audiences/all ages), M (mature), R (restricted — those under 17 require supervision), and X (no one under 16 admitted). In the 1980s, Gremlins and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom received pushback for their PG ratings, which led to the creation of PG-13.

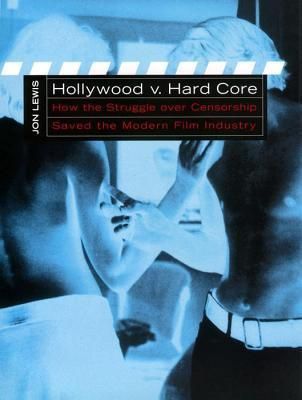

Jon Lewis, author of Hollywood v. Hard Core: How the Struggle Over Censorship Created the Modern Film Industry, argues that the ratings are subjective by design. We can see what he means in how certain movies are declared to be far more “adult” than others. For example, the movie Blue Valentine almost received an NC-17 rating because of a scene in which Ryan Gosling’s character performs oral sex on Michelle Williams’ character.

Gosling spoke out against this because he felt it stigmatized the act of a woman receiving pleasure, whereas other movies with oral sex performed on men tended to receive simple R ratings. This was also the birth of the feminist Ryan Gosling meme — if you remember that time on the Internet, this is your sign to stretch your weary bones.

The MPAA also historically gives R ratings or higher to movies with queer characters, even when there are no sex scenes. One of my favorite movies, Pride, received an R rating for simply dealing with the topic of AIDS and queerness. There are a few kisses between men and no nudity.

What Does This Mean for Books?

Parents don’t even seem to like the MPAA rating system all that much, criticizing it for desensitizing children to violence. So what’s the argument for a rating system for books?

The idea is that kids should not have access to stories that could upset them or expose them to difficult topics. The rating system outlined on Book Cave uses seven categories (crude humor/language, profanity, drug and alcohol use, kissing, nudity, sex and intimacy, and violence and horror), and then rates each category on a scale from All Ages to Adult+. The book is then weighted for a final rating. Common Sense Media gives detailed advice about how to assess various aspects of books and how to choose them for children, and promises to provide detailed reviews to help parents, guardians, and other stakeholders make decisions.

Age ranges and reading levels are also very hit-or-miss. Reading levels were introduced in schools to make sure students were keeping up with reading demands, so there were lots of numbers introduced to explain these levels. The important part of reading levels is that children should be able to ingest and understand the majority of the book they’re reading so they don’t get discouraged. However, kids should challenge themselves with books theoretically outside of their level so they don’t get bored.

If reading levels are determined by word difficulty alone, that can also make books look less complex than they are. Age ranges and reading levels are somewhat necessary for educators to build curricula, but kids should always be allowed to seek books outside of their “level” or assigned classroom work. I’m an advocate of the method “bring kid to library and let them explore for three hours,” as my caretakers did for me.

There are problems with rating systems that use categories to determine appropriateness as well. A book might not have violence in it explicitly, but it could have imagery that gives your child a nightmare. We can’t determine how kids will react to reading in general, so over-arching rules and categorical rating systems are limited.

Rating systems that determine how “adult” a book is also impose a certain kind of life experience on childhood. They present a monolithic idea of maturity: a child can only read about violent content when they’re of the age to be familiar with it. There are children in the world who are familiar with curse words, or have experience with violent or upsetting events. “Milestones” in childhood are impossible to pinpoint because people’s life experiences are so wildly different.

Reading about difficult topics, whether or not children have experienced them, can be a good way to process complex emotions. It’s also an important way for children to develop language and understanding around “inappropriate” topics.

How Levels and Ratings Work in Real Life

At the surface, none of this sounds necessarily bad. Parents obviously want kids to read, but they don’t want kids diving into books with intense horror that will scare a 7 year old or overt descriptions of sex before a parent has had ‘The Talk’ with their kid.

There are so many ways that these restrictions fail young readers. Saying that you can’t read a book until you’ve had an experience is very silly. For example, if a book includes a description of a person getting their first period, you could theoretically say that is inappropriate for 11 year olds. Well, what if you’re one of those people who got their period at a very young age? Or what if you don’t get it until you’re a little older? There are simply too many differing life experiences to impose a general rule of propriety on all kids and teens.

In covering censorship news, Book Riot routinely comes across groups like Moms for Liberty advocating for “parental rights.” Danika Ellis explained the shortcomings of their kind of thinking:

“Groups like this advocating for “parental rights” assume that parents are inherently conservative. They treat their perspective as ‘common sense,’ that no parent would want their kids to have access to a picture book that shows a boy wearing a dress, or their teenager to be able to read a book with a sex scene in it, or one that teaches safer sex practices, or one that discusses rape. But there are just as many (and likely many more) parents who want their kids to be able to access LGBTQ+, BIPOC, and diverse books.”

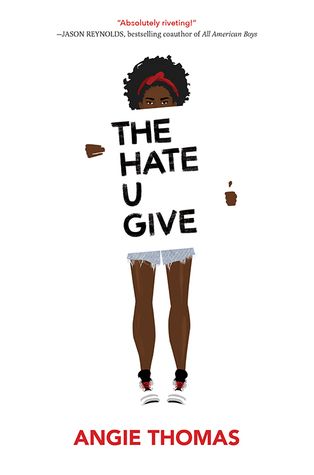

These parental rights groups are also obsessed with censoring and banning books that deal with race, hiding the very fact of non-white people from their lily-white delicate students. Mega-popular YA books All American Boys and The Hate U Give are routinely challenged and banned by parents who feel the subject matter is inappropriate for children. I have to assume they’re using the categories of profanity and violence to support their bigoted arguments.

But How Do We Protect the Children?

I’m not a parent, so I can’t viscerally understand the need to protect your child from the various horrors of the world. The technology available to kids means that we have very little control over what they see. We can keep telling kids not to talk to strangers, but much of the information out there is out of our control.

I see how people obsessed with controlling kids’ access to information landed on books. It’s a discrete physical item that you can remove from a library, a school, or your child’s bookshelf. Removing something “dangerous” gives the illusion of safety. We’ve saved the children by not allowing them to read Maus!

I’m personally of the opinion that all reading is good reading. Even if a kid doesn’t like a book, it’s an opportunity for a conversation. If they read something particularly scary or upsetting, it’s an opening to discuss potentially difficult topics in a safer way. I would prefer my child learn about upsetting facts through a book than through encountering them in real life. Words on a page are a safer way to experience and explore emotions.

No matter what we want to protect our children from, there’s probably a kid out there who has experienced something similar. Fiction is a safer place to explore difficult topics, but it is important for parents to find books that handle difficult topics with care. The resources I recommend for finding books for your children already exist: children’s librarians, summaries on back covers, and discussions with other people about what they thought of particular books.

I think a lot of us want to construct an impenetrable circle of safety around young people. I’m deeply upset by how many awful things happen to children every day, and I wish I could preserve their innocence by clicking my fingers and stopping school shootings in the United States. Taking away books doesn’t save them, though. Words on the page are ultimately much safer to experience than anything in the real world, but books are easier to point to as the problem. The real world and the terrible things that happen to children are harder to control and harder to stomach.

Book Riot covers censorship news and ways to resist book bans, and you can also check out these books for beginning readers and tips for helping beginning readers.