20 Must-Read Books Set in Spain by Spanish Authors

It’s always been the case that when I travel, I like to read novels that are region-specific. That’s been true for a long time; but in the last few years, as I became more aware of the lack of translated literature and the need to read more diversely, I made my plan even more particular. Now, when I travel somewhere, I want to read books not only set in the place but written by someone who lived or was from there, preferably translated from the original language.

So when I went to Mexico City from Chicago, I read Caramelo by Sandra Cisneros; when I went to England, I read Jane Austen. And when I went to Spain, I dug deep into lists of Spanish authors, of books to read before, during, and after my trip that were written by Spanish authors and were set in Spain. I included books written in Catalan and Galician, as they are important national identities of regions that have also pushed for independence.

I should note that I attempted to make my list inclusive of authors of color, but struggled to find translated non-white authors writing in Spain. If you have recommendations, please share them with me on Twitter—I would love to hear them! It’s also worth noting that there are many fantastic authors and novels out there that I would have loved to dig into on my trip and on this list but that are still untranslated, highlighting once again the importance of an international outlook for our reading lists.

So here it is: my reading list. Some of these I read in Spain, with a glass of wine in the cobblestone maze of Barcelona’s Barri Gótic or under the orange blossom trees in Seville. Some of these I read after, during the pandemic, missing the glorious feeling of exploration, living vicariously through the novels. And others, I still have to read, saving them to spread over the next few months. I hope you, too, can dive into these books, whether it be someday in the future for your travels or today to live through the pages.

Death in Spring by Mercè Rodoreda, translated by Martha Tennent

I read Death in Spring on a beach in La Barceloneta, the breeze chilly and the sky a bluish grey. It’s a strange, twisting, lovely novel, written originally in Catalan, that gives a folkloric look into a small town that has rigid, bizarre, and often violent customs. Through the eyes of a young boy growing up, Rodoreda shows us these strange rituals and the attitudes of the people who enact them, and in an allegorical fashion, strikes at the harsh laws and restraint of Franco’s Spain.

The Dinner Guest by Gabriela Ybarra, translated by Natasha Wimmer

This is a deeply affecting semi-autobiographical novel. In 1977, Ybarra’s grandfather was kidnapped by Basque separatists, went missing, and then was found murdered. While the story haunted Ybarra’s childhood, many of the details were hushed and kept silent until she decided to dig into their history after her mother’s death, unearthing newspaper articles and discovering as much of the truth as she could. The result is a somber, poetic exploration of grief, family history, and silence in politics.

A Heart So White by Javier Marías, translated by Margaret Jull Costa

Marías is one of Spain’s most celebrated novelists. In A Heart So White, Juan, a professional translator, finds himself often crafting words, tweaking messages, holding a power over language. When he gets married, he finds himself digging into his father’s history and interiority, and finds complicity and darkness in the shadows of his own story. “My hands are of your color; but I shame / To wear a heart so white.” Marías pulls from this line from Shakespeare’s Macbeth as he puts this novel together.

Beautiful and Dark by Rosa Montero, translated by Adrienne Mitchell

Award-winning journalist and novelist Rosa Montero, known for her feminist novels and her work for newspaper El País, combines the real and the fantastic in Beautiful and Dark. It’s a story about orphan Baba, a young girl living with relatives in El Barrio, struggling with the dark adult world that surrounds her and her neighborhood. She is lucky to meet Airelei, who shares myths and tales. The book brings together magical fairy tale horror with a social realist bent.

The Winterlings by Cristina Sánchez-Andrade, translated by Samuel Rutter

After years of exile following their grandfather’s murder during the civil war, two sisters return to their cottage in the small, idiosyncratic village of Tierra de Chá in Galicia in the 1950s. Suspicion begins to rise about the sisters when they attempt to stand in for a movie part—why are they back? Meanwhile, other mysteries rage on, such as, why won’t the town speak about their grandfather’s death? Secrets and mysteries haunt the tale told in this novel by contemporary author Cristina Sánchez-Andrade.

The Frozen Heart by Almudena Grandes, translated by Frank Wynne

When Alvaro notices an attractive stranger at his father’s funeral, his curiosity is piqued. Who is she? And why does no one seem to know? When his family then receives a large amount of money, Alvaro goes digging, and discovers an old folder of letters from the 1940s—and finds out that the woman is Raquel Fernandez Perea, whose parents fled Spain during the Civil War. This is a spanning epic about a war that shook Spanish society.

The Happy City by Elvira Navarro, translated by Rosalind Harvey

I picked this book up in a small used bookstore in Barcelona, its shelves packed with English language books, hidden away on a beautiful street. Navarro has been hailed as one of the rising stars of Spain’s literature scene: in this novel, she tells the story of Chi-Huei, a Chinese son of immigrants, and his friend Sara, a girl intrigued by a homeless man. The book is a coming-of-age tale grounded in frustration, social pressures, and disillusionment, all energized by Navarro’s sharp, complex writing.

The Time in Between by María Dueñas, translated by Daniel Hahn

I read this chunky historical fiction novel on my plane ride home from Spain, taking refuge in its pages. It’s a story about a bold woman named Sira who casts out for independence when the man she loves leaves her penniless. With the help of strong female allies, she becomes a haute couture dressmaker in Tetouan in Morocco and soon becomes entangled in politics. It’s a long novel that breezes by, a huge international bestseller that hasn’t gotten nearly enough attention in the U.S.; it spans a lot of history in its pages, with compelling friendships and complex side characters, and by the end of it, I was feverishly rooting for Sira.

The Yellow Rain by Julio Llamazares, translated by Margaret Jull Costa

Only one man remains in Ainielle, a small deserted village high up in the Spanish Pyrenees. That man, old and in solitude, wanders, the “yellow rain” of autumn leaves coming down around him as he looks back at his life and town, as he remembers the people and the life that were once with him. Llamazares is a contemporary author focused on the rural life of Spain, what has been left behind as the obsession and fixation on the cities grows, himself originally from small village in the region of León.

Literature™ by Guillermo Stitch

This strange sci-fi noir novella features a man named Billy Stringer. Dressed as a clown and having just messed up a big assignment at work, he’s now realizing that someone is out to kill him. This isn’t particularly surprising to him—he’s an assassin, and he’s also a bookworm in a world where fiction is banned for the sake of efficiency. But he’d prefer to survive, at least long enough to see his girlfriend Jane and explain to her what’s happening. Dystopian and smart, this novella won gold at the 2019 Independent Publisher Book (IPPY) Awards.

The Family of Pascual Duarte by Camilo José Cela, translated by Anthony Kerrigan

This classic is a 1942 novel by a Spanish Nobel laureate. Disturbing and dark, this short novel features a man who has decided that violence is the only way to get what he wants, to exist in the world that is deterministic and unkind. Cela writes of the human capacity for violence, for war, and here he is writing in the form of Spanish realism termed “miserabilism,” which is more or less what it sounds like. The difficult, unlikeable narrator is portrayed against the darkness of his own life. This novel was banned when it first came out, causing an uproar.

All is Silence by Manuel Rivas, translated by Jonathan Dunne

Three young friends, Fins, Brinco, and Leda, spend their days exploring the seashore and picking through what they find. When they stumble on a cache of whisky, they think they have it made—until they find out who it belongs to. This novel, written originally in Galician, is a story about silence—about the historical and oppressive weight of silence that hovers over the politics of this town, this region, and of the culture of masculinity that pervades. As Fins, Brinco, and Leda grow up, their relationships shift, and Rivas’s strange prose gives the entire thing an atmospheric feel.

The Anatomy of a Moment: Thirty-Five Minutes in History and Imagination

by Javier Cercas, Translated by Anne McLean

Cercas is generally best known as a novelist, but this time, he felt he had to turn to nonfiction instead. After the end of Franco’s reign, Spain held a democratic vote for a new prime minister, but at the moment of the Parliament vote, in a filmed session, a band of right-wing soldiers interrupted the vote and ordered everyone to get down. Three men refused, remaining sitting in their seats instead—a moment of rebellion that has taken on the semblance of myth. A bestseller in Spain, this book captures that moment in descriptive writing.

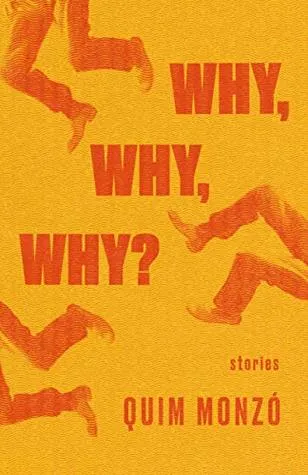

Why, Why, Why? By Quim Monzó, translated by Peter Bush

Why, Why, Why? Stories is a collection of cynical, absurd tales by Catalan writer Monzó. His stories are blunt and strange, about mixing up faces and names, about the inability to connect, the strange sadnesses that burden people’s everyday lives. It won points for me for “Married Life,” a cynical story about sex becoming stale after marriage, a subject too common already in literary fiction, but this one hurt, showing Monzó’s skill at hitting precisely the point of pain, of disconnect.

La Casa de Bernarda Alba by Federico García Lorca, translated by Emily Mann

When her husband dies, mother Bernarda Alba grows controlling and fierce, keeping her five adult daughters locked in her home, insisting that they institute a strict eight-year mourning period, and trying to even control their day-to-day communication within the home. It’s a tense, tragic sort of play, a work of female strength and sexual repression, of a culture of silence and control, as the mother keeps her daughters under lock and key, and as the daughters strive to escape. Set in Andalusia, this tragedy is one of Lorca’s final works.

Homeland by Fernando Aramburu, translated by Alfred MacAdam

Patria in its original Spanish, Homeland is a contemporary novel that captures the tense and difficult story of two Basque families in the midst of the violent separatist movement of the ETA. Nonlinear and populated by a multitude of small chapters, Aramburu captures the complex and chaotic lives of these two families, spanning the 1980s to 2011. The author has been critically acclaimed, and the book has run through many editions in Spain, causing a stir.

The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón, translated by Lucia Graves

The fact that this is an obvious inclusion doesn’t make it any less true: Zafón’s novel is a masterwork, a fascinating mystery of a novel that I read walking along the cobblestones of the Gótic, sitting overlooking the city at Parc Güell, drinking an absinthe in Bar Marsella. A gorgeous novel about a maze of forgotten books and a spiraling mystery, a thriller of sorts about a boy named Daniel who falls in love with a book, a book with a dark history of its own. This is the classic Barcelona novel.

The Best Thing That Can Happen to a Croissant by Pablo Tusset, translated by Kristina Cordero

Barcelona author Pablo Tusset’s debut novel features Pablo “Baloo” Miralles, an internet blogger and pleasure seeker, rarely awake by day, a black sheep of the family who is brought in when the president of the family business, his older brother, disappears. Reluctantly playing detective, Miralles sets out to try and find his brother, in a novel that is wicked, funny, and quickly became a bestseller in Europe.

Solitude by Victor Català, translated by David H. Rosenthal

Caterina Albert is a Catalan author who published under the name of Victor Català. In 1905 she published Solitud, a novel that told the story of a young woman struggling to assert her independence, a feminist text that was fairly revolutionary at the time and that contributed to the Catalan modernist movement as well. Solitude tells the story of Mila, a peasant girl who marries Matias, moving to a remote area up in the mountains where both of them begin to feel themselves pulled into different directions, and to different people.

Nada by Carmen Laforet, translated by Edith Grossman

When I first picked up this book in a bookshop in Barcelona, I didn’t expect to fall in love as deeply as I did. Young Andrea comes to stay with her relations in a house on Calle de Aribau, in order to attend university. She finds a cast of characters both intimidating and difficult: from her superstitious aunt Angustias to her uncles Juan and Román to Juan’s wife, the gambling, beautiful Gloria. As Andrea becomes close with friend and classmate Ena, she grows more and more introspective, mature, and determined to succeed. I read this gothic, gorgeously written novel on the train from Barcelona to Seville, swallowing up its descriptions, breathing in Andrea’s resolve. It stuck with me even after I had left Spain, and ended up being my favorite book I read on my travels.