The State of Book Banning in the UK

The UK and the U.S. have long had a “special relationship,” but sadly, it seems that “special” can often be used as a synonym for “toxic.” Over the last few years, both countries have seen a massive swing to the right politically. (Although the UK just elected a Labour government, this particular incarnation of Labour is a far cry from the party’s socialist roots, and even calling it centre-right would perhaps be a bit too charitable.) During the fourteen years under a hard-right Conservative government, the UK dropped far down the list of best countries for LGBTQ+ people, mostly thanks to a concerted campaign by politicians, right-wing news outlets, and bigoted celebrities to attack and stigmatise trans people. Migrants have also been a target for attacks, with the previous government’s focus on creating a “hostile environment” (that the new government shows no signs of overturning) and racism and Islamophobia increasing to the point where politicians are now perfectly comfortable saying that some cultures are “less valid” than others.

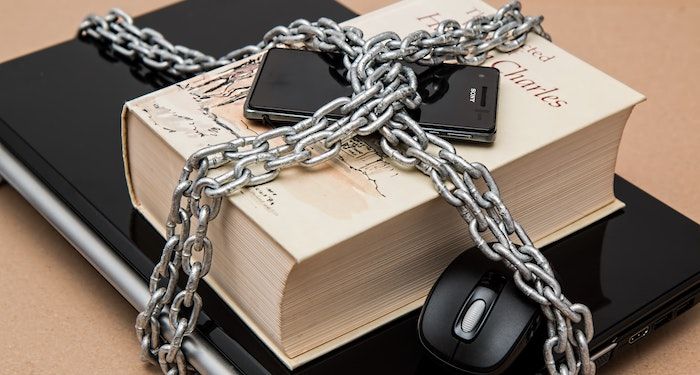

So far, the UK government has not introduced any legislation banning books comparable to the recent laws that we’ve seen in the US. Not that we haven’t had such legislation in the past: I grew up under Section 28, one of the most notorious evils of the Thatcher government, which banned schools and public libraries from “promoting homosexuality” (translation: allowing children to know that LGBTQ+ people existed). Schools were not allowed to use any materials that acknowledged the existence of LGBTQ+ people, and to comply with this, school libraries were scoured for books that might include a gay character so they could be removed. Russell T. Davies’s brilliant drama series It’s a Sin has a scene where one of the characters, a gay man, has to censor the library in the school where he’s working, one of many powerful moments in a gut-punching series.

While Section 28 was repealed 20 years ago, it has cast a long shadow. Many writers around the same age as me have used its legacy as inspiration for their work. In his dystopian book The Outrage, William Hussey uses the term “Section 28” to describe one of the tyrannical emergency orders created by the fascist government as a direct reference to a real-world government’s attempt to erase LGBTQ+ people.

There is currently no outright successor to Section 28 on the books, but the education guidelines produced by the Conservatives (and published without challenge by Labour) have been described by many as “a new Section 28“. They treat trans existence as a “contested ideology” and promote outing trans students to potentially unsupportive and possibly abusive parents.

While there are currently no laws or government initiatives to ban books, book banning is still happening in the UK. Index on Censorship, an organisation devoted to combatting attempts to limit free speech and expression, recently broke the story that school librarians are being pressured by parents to remove LGBTQ+ books from their school libraries. According to the investigation carried out by Index on Censorship, over half of the school librarians they approached had been asked to remove books with “LGBTQ+ themes”. Librarians reported being pressured to remove books that had rainbows on the cover, mentioned trans people, or featured events such as Pride.

At the moment, the focus seems to primarily be on LGBTQ+ books. Bans in the U.S. have also focused on books with characters of colour, like Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison, but Index on Censorship only heard of one situation where a library in the UK had been pressured to remove a book because of “anti-white racism”, and the book was ultimately allowed to stay.

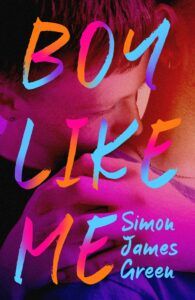

Anti-LGBTQ+ pressure is not only making schools remove books: authors are also being directly affected. Two years ago, children’s and YA author Simon James Green was banned from visiting a school after the local Catholic diocese, which oversaw the school, overturned the school’s decision to have him visit. The ban made the national news and led to protests by local students, teachers, and LGBTQ+ groups. Sadly, the diocese doubled down, and the ban remained. Green was also subjected to horrific abuse, receiving homophobic messages and threats from anonymous sources.

I spoke to Green about the Index on Censorship report, and he said,

“One of the worrying aspects of the UK situation is that a lot of this is happening under the radar, with certain books being quietly removed from shelves or simply not acquired in the first place. I know this is happening for some books (although none of mine, that I’ve heard of) from my conversations with school librarians, but it’s obviously anecdotal evidence. It isn’t the librarians doing this willingly, either — school librarians all over the country are doing brilliant work, stocking a range of diverse titles and defending them to the hilt, if they need to. However, they’re coming under pressure from some school leaders, or from parents. I’ve heard stories of secondary school libraries which aren’t allowed to have an LGBTQ+ book display during Pride month, for example. I know of authors who have been asked to remove the LGBTQ+ content of their author talks. It’s shocking. LGBTQ+ people exist. Get over it. Why are we still having this conversation?”

The “under the radar” nature of book bans mentioned by Green — also known as quiet censorship, soft censorship, and self-censorship — is certainly concerning, as it makes it difficult to know which books and authors are being affected. I have spoken to other authors who have been asked on school visits not to bring any books from their backlist that include LGBTQ+ characters and not to talk about LGBTQ+ people as part of their author events.

I spoke to Jo Cotterill, an author of several contemporary stories for middle grade and YA audiences, who told me that a school she was visiting told her not to bring or mention one of her books, A Storm of Strawberries because it includes lesbian characters. To writers of my age, this feels like Section 28 all over again, albeit without explicit government backing.

Why has this insidious book banning happened? While Index on Censorship’s report shows that books are being removed because of parent complaints rather than government legislation, there can be no doubt that this worrying trend is a result of the systemic, organised undermining of LGBTQ+ rights in the UK. Trans people’s existence is treated as “contested ideology” even by parties who consider themselves “progressive,” and LGBTQ+ groups have repeatedly warned that this will lead to a wider call for a rollback of rights in schools.

The previous government included politicians who called for “transparency” regarding sex education materials, which, reading between the lines, seemed to be the first step in an attempt to remove references to LGBTQ+ relationships or any challenge of cisheteronormativity. The ex-MP who proposed this Bill, Miriam Cates, lost her seat at the election, and she has since written op-eds calling for a ban on sex education altogether.

In our interview, Green commented, “I’m just really depressed by the ill-informed rhetoric and how the so-called ‘culture wars’ have added fuel to the fire. All anyone is trying to do is help LGBTQ+ young people feel seen and understood and also help all young people understand their friends and peers a little better — to prepare them for the diverse world in which they are going to be living and working. Appreciating that we’re all different, and that difference is nothing to fear, makes the world a happier and easier place to live.”

What can be done to stop this dangerous, regressive trend? Fortunately, a great deal. Schools need to stand up to parents and be prepared to push back in order to protect students and authors. Ideally, schools should preempt any book banning attempts by setting up policies on library content and make it clear that they will only remove books for legitimate reasons (for example, age-inappropriate sexual references or violence). Publishers and professional organisations can also use their collective power to back up authors who may lose income because of not being invited for school visits or because of their books being removed from libraries. The Society of Authors has already spoken out against book banning following the publication of the Index on Censorship report.

Authors and readers in the UK could take cues from banned books organisations that are working in the U.S., such as the groups who have come together to organise Banned Books Week. There’s also a huge potential for authors to support each other. While writing is a solo profession, there are many official and unofficial platforms for support groups, and whether you’re leaning on fellow writers through your SCBWI group or your writer buddies’ group chat, it’s important to have that community for support in the face of bigotry and targeted harassment.

Green suggested,

‘To any authors, particularly in the UK, I would say get in touch. It can be a very lonely and frightening experience, and it’s often hard to ‘go public’ with it because you’ll inevitably attract abuse from all the usual suspects who love to accuse authors of being ‘groomers’ and all the other unoriginal accusations which we’ve been dealing with for decades. There’s a strong network of people in the UK pushing back against this, and who can offer practical advice and support, but we need to know what’s going on and we need to work together. For students who hear of books being removed, if you’re able, and it’s safe to, push back. Ask for a meeting with the librarian or head teacher. Make your case. Highlight why diverse books are important. Ask your school to stand up for all their students and the freedom to read.”

Looking towards the future, everyone — readers, writers, publishers, and other organisations — needs to be aware of any efforts to bring in legislation that officially bans books and ensure that it is challenged robustly from the start. Finally, as the adults in this situation, it’s our responsibility to continue supporting LGBTQ+ students throughout all this. Grassroots, youth-led organisations such as Trans Kids Deserve Better, who recently completed a direct action protesting the Department of Education’s decision to publish the Conservatives’ anti-trans guidelines, are fighting important battles. These activists are doing amazing work, but children and teens should not have to be responsible for protecting their own right to exist peacefully.

Book banning in the UK can be stopped; we just have to take the threat seriously and keep fighting. In our interview, Green noted that “while their side relies on hate and fear, ours is about love and acceptance — and that’s why we will ultimately win because hate destroys and love nurtures. Love always wins in the end. It’s just such a waste of time and energy that we have to fight to get there.”

If authors, readers, publishers, and schools pull together, we can fight book bans in any form and ensure that young people get to see themselves and society reflected in the books they read.

If you’re looking for more resources on fighting censorship, Kelly Jensen has been tracking censorship, with a U.S. focus, every week in the Literary Activism newsletter. Many of the resources are also applicable to the UK, so check out How To Fight Book Bans and Challenges and How to Fight Book Bans in 2024.