Blank Generation: On Discovering Oral History

Currently based out of Vancouver, British Columbia, Rachel Rosenberg is a library technician and published writer; at 14, a short story of hers appeared in Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul 2 and she can therefore be considered a literary equivalent to the little redheaded girl from 1982’s film adaptation of Annie. She has produced freelance articles, creative nonfiction essays and short stories.

When I was growing up in suburban Montreal, my dad and I used to go to the local library together almost every week. There wasn’t much to do in Ville St. Laurent; it was close enough to downtown that most people left the area to attend events, so we had a mall but no movie theatre and coffee shop options were limited to Dunkin’ Donuts and Tim Hortons. Our library was large and spacious with three levels of books to unearth. I’d always been a voracious reader—in third grade, I borrowed my dad’s copy of Stephen King’s Firestarter because I was looking for a more complex read than what I was then enjoying: a series of Full House spin-off novels.

I wasn’t great in school, struggling with math and science in a way that made the classroom a place of frustration and anger. School was where I dragged myself every morning, uniform slightly askew out of spite, and got told that I did everything wrong. I spent a lot of time in detention, mostly for skipped classes and untucked uniform shirts (I was especially resentful because our school forced us to wear a uniform despite the fact that it wasn’t a private school—what other public school in North America did that?). School made me feel stupid, whereas the library let me feel curious and hopeful. Books were filled with writing that didn’t require a thesis statement, and I felt that authors were my people.

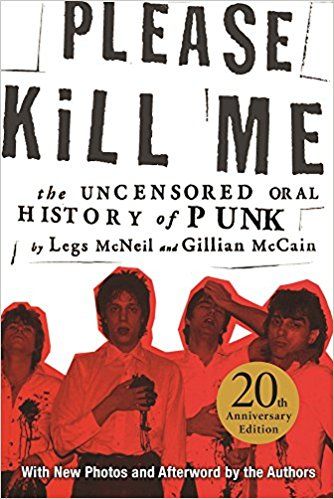

It was there, in the shelves of adult nonfiction, that teenage-me spotted a red book spine with the words Please Kill Me written in torn paper style, like a kidnapper’s note. Holding the book in my hands, it felt illicit: the skinny, ill-looking men clutching their bleeding hearts; the aggressive phrasing; and pages full of drug addiction, drag queens, and general New York City badassery. The full title: Please Kill Me: An Oral History of Punk Rock. Though I’d never listened to punk rock at the time, the cover and first few pages worth of stories had me intrigued. It was funny and wild, these pages inked with lives that were unimaginable to me. Plus, for a furious girl, the more I read about punk the more I wanted to find these CDs in my local HMV.

It was there, in the shelves of adult nonfiction, that teenage-me spotted a red book spine with the words Please Kill Me written in torn paper style, like a kidnapper’s note. Holding the book in my hands, it felt illicit: the skinny, ill-looking men clutching their bleeding hearts; the aggressive phrasing; and pages full of drug addiction, drag queens, and general New York City badassery. The full title: Please Kill Me: An Oral History of Punk Rock. Though I’d never listened to punk rock at the time, the cover and first few pages worth of stories had me intrigued. It was funny and wild, these pages inked with lives that were unimaginable to me. Plus, for a furious girl, the more I read about punk the more I wanted to find these CDs in my local HMV.

What makes an oral history so distinct from a regular ol’ history is the stories from the people involved, not just the musicians and journalists, but groupies and club managers. The people who are on the sidelines often have great insights because the pressure wasn’t on them in the same way; they were watching as history was made. A good oral history will give the reader a feel for the personalities involved: you read Lou Reed in his own meandering, strange words, or hear the frustrated ranting of a New York Doll complaining about his fellow band-mates. The unfiltered structure gives a visceral, hands-in-the-dirt vision of the time and place. To this day, I think Please Kill Me did it the best out of all the punk rock histories I’ve read—the characters are so vibrant that it really immersed me in the scene of 1970s NYC punk.

Cut to many, many years later. Oral histories have suddenly become a fad in pop culture reporting, and not just in books, as magazines have begun reuniting bands and the casts of popular TV shows. Plenty of book-form oral histories have been published in the last couple of years: Meet Me in the Bathroom, about the New York City music scene between 2001 and 2011, Everybody Loves Our Town, about Seattle’s grunge scene, and As If, an oral history of the movie Clueless. In the mid-’90s, though, I’d never read anything like that.

The book introduced me to new bands that quickly became favorites, revealing that punk is more than leather jackets and a bad attitude, but myriad different styles and characteristics. It was experimentation, with noisy, technically impressive bands like Television. It was dorky, if you listen to The Ramones’s many love songs. It was comforting, listening to a song like Richard Hell’s “Blank Generation” and realizing that my teenage apathy was normal. Finally, it felt like a world that was attainable because the whole point of it was doing what you wanted and finding a way to make it work.

Without a library, I’d have never made this discovery. Now, I work as a library technician, surrounding myself with page after page of different worlds, and helping people find writing that will change their lives. 1970s punk is still my favorite, powering me up to fight against a world that often seems to want us to feel small and stupid.

Other recommended music histories (not oral histories but they really round out Please Kill Me): England’s Dreaming by Jon Savage, Rip It Up and Start Again by Simon Reynolds, and From the Velvets To the Voltoids by Clinton Heylin.