How the American Girl Series Shaped My Reading, Imagination, and Humor

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

As an elementary school girl in the ’90s who loved reading and history, I was the target consumer for the first generation of the American Girl dolls. The dolls were all preteen girl characters from different ethnicities, eras, and regions. For my 8th birthday in July 1997, I got a Kirsten doll—one of the three original historical dolls. Kirsten Larson is a Swedish immigrant who lives with her family on the Minnesota frontier in the 1850s.

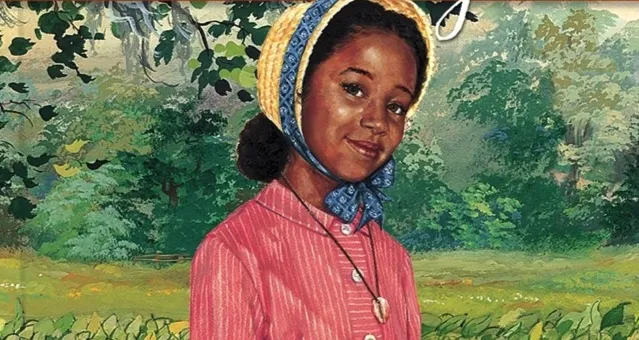

Each doll had her own clothing, accessories, furniture, and book series. Collecting all of it would have been very expensive, but I kept the doll and her items in pristine condition. If I’d been a couple of years younger, I wouldn’t have taken good care of the doll or been interested in the history yet. I had one American Girl doll with a bed and a few outfits, but I read all the books. If I’d read the books first, I would have chosen Addy Walker, an African American girl who reaches freedom, instead.

In 1997, I started third grade and was too young to learn about slavery in detail in school. However, I read about it in Connie Porter’s powerful Addy books. Of course, as a white kid in the 20th century, I could never understand how it felt to be enslaved. Although it was fictional and written for children, Addy’s series taught me about slaveowners brutalizing people and separating families in an individual way that school hadn’t yet. The series helped me read diversely, learn about people and experiences far beyond myself, and made me a lifelong historical fiction fan.

For Christmas, almost six months after I got my Kirsten doll, my parents bought me the computer game The American Girls Premiere. The game allowed players to create multiple-act plays starring the characters. We could select the main character, her supporting cast, sets, props, lighting, and more. Computer animation and AI from the ’90s would seem slow and clunky today. As my cousins and I typed dialogue, we realized that the robotic voice would speak in run-on sentences unless we punctuated them. We found it hilarious that it hadn’t been programmed to pronounce Addy’s friend M’Dear’s nickname correctly. We made each other laugh uproariously just by making the deadpan voice say, “Hell-O, EM-Deer!”

Once we learned that the game could be unintentionally funny, we started using it in ways the creators had probably never imagined. Why couldn’t a white man in a colonial, powdered wig solemnly recite nursery rhymes or ’90s song lyrics? We used keyboard commands to position characters, but they could also levitate, walk through walls, or spin in circles. We added the bear sound effect from Kirsten’s stories at random moments.

Soon, we got tired of our own attempts at absurdist humor or just recreating scenes from the books. I realized that I could basically write fan fiction by continuing the books’ stories. Obviously, I spent a lot of time joking with friends and reading, writing, and playing on my own.

I began creating my own literary adaptations, using the characters and sets from the game. With her ornate, colonial dresses and sets, 1770s Felicity could be a princess, with a boy in silk breeches as a prince. I read Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess and considered the 1995 adaptation one of my favorite movies. I “cast” Samantha Parkington, a wealthy, white girl circa 1904, as Burnett’s protagonist, Sara Crewe. Once I’d done that, “casting” Samantha’s friends and family as Sara’s dad Captain Crewe, the servant girl Becky, or headmistress Miss Minchin was easy. For obvious reasons, it was impossible to mix and match characters or sets from different eras, but it would have let me adapt many more stories.

The American Girls franchise provided me with many hours of reading and creative play—serious or hilarious. It helped me to empathize with fictional characters from diverse backgrounds. It also spurred my development as a writer who loves interpreting, reimagining, and responding to literature. I didn’t need any computer piracy or coding skills to “hack” the game from its intended use. I even recorded my own audio using my computer’s microphone. Years later, in high school and community musical theater, I still remembered my early obsession with sets, casts, and other elements of plays.

In 1997, I started third grade and was too young to learn about slavery in detail in school. However, I read about it in Connie Porter’s powerful Addy books. Of course, as a white kid in the 20th century, I could never understand how it felt to be enslaved. Although it was fictional and written for children, Addy’s series taught me about slaveowners brutalizing people and separating families in an individual way that school hadn’t yet. The series helped me read diversely, learn about people and experiences far beyond myself, and made me a lifelong historical fiction fan.

For Christmas, almost six months after I got my Kirsten doll, my parents bought me the computer game The American Girls Premiere. The game allowed players to create multiple-act plays starring the characters. We could select the main character, her supporting cast, sets, props, lighting, and more. Computer animation and AI from the ’90s would seem slow and clunky today. As my cousins and I typed dialogue, we realized that the robotic voice would speak in run-on sentences unless we punctuated them. We found it hilarious that it hadn’t been programmed to pronounce Addy’s friend M’Dear’s nickname correctly. We made each other laugh uproariously just by making the deadpan voice say, “Hell-O, EM-Deer!”

Once we learned that the game could be unintentionally funny, we started using it in ways the creators had probably never imagined. Why couldn’t a white man in a colonial, powdered wig solemnly recite nursery rhymes or ’90s song lyrics? We used keyboard commands to position characters, but they could also levitate, walk through walls, or spin in circles. We added the bear sound effect from Kirsten’s stories at random moments.

Soon, we got tired of our own attempts at absurdist humor or just recreating scenes from the books. I realized that I could basically write fan fiction by continuing the books’ stories. Obviously, I spent a lot of time joking with friends and reading, writing, and playing on my own.

I began creating my own literary adaptations, using the characters and sets from the game. With her ornate, colonial dresses and sets, 1770s Felicity could be a princess, with a boy in silk breeches as a prince. I read Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess and considered the 1995 adaptation one of my favorite movies. I “cast” Samantha Parkington, a wealthy, white girl circa 1904, as Burnett’s protagonist, Sara Crewe. Once I’d done that, “casting” Samantha’s friends and family as Sara’s dad Captain Crewe, the servant girl Becky, or headmistress Miss Minchin was easy. For obvious reasons, it was impossible to mix and match characters or sets from different eras, but it would have let me adapt many more stories.

The American Girls franchise provided me with many hours of reading and creative play—serious or hilarious. It helped me to empathize with fictional characters from diverse backgrounds. It also spurred my development as a writer who loves interpreting, reimagining, and responding to literature. I didn’t need any computer piracy or coding skills to “hack” the game from its intended use. I even recorded my own audio using my computer’s microphone. Years later, in high school and community musical theater, I still remembered my early obsession with sets, casts, and other elements of plays.

In 1997, I started third grade and was too young to learn about slavery in detail in school. However, I read about it in Connie Porter’s powerful Addy books. Of course, as a white kid in the 20th century, I could never understand how it felt to be enslaved. Although it was fictional and written for children, Addy’s series taught me about slaveowners brutalizing people and separating families in an individual way that school hadn’t yet. The series helped me read diversely, learn about people and experiences far beyond myself, and made me a lifelong historical fiction fan.

For Christmas, almost six months after I got my Kirsten doll, my parents bought me the computer game The American Girls Premiere. The game allowed players to create multiple-act plays starring the characters. We could select the main character, her supporting cast, sets, props, lighting, and more. Computer animation and AI from the ’90s would seem slow and clunky today. As my cousins and I typed dialogue, we realized that the robotic voice would speak in run-on sentences unless we punctuated them. We found it hilarious that it hadn’t been programmed to pronounce Addy’s friend M’Dear’s nickname correctly. We made each other laugh uproariously just by making the deadpan voice say, “Hell-O, EM-Deer!”

Once we learned that the game could be unintentionally funny, we started using it in ways the creators had probably never imagined. Why couldn’t a white man in a colonial, powdered wig solemnly recite nursery rhymes or ’90s song lyrics? We used keyboard commands to position characters, but they could also levitate, walk through walls, or spin in circles. We added the bear sound effect from Kirsten’s stories at random moments.

Soon, we got tired of our own attempts at absurdist humor or just recreating scenes from the books. I realized that I could basically write fan fiction by continuing the books’ stories. Obviously, I spent a lot of time joking with friends and reading, writing, and playing on my own.

I began creating my own literary adaptations, using the characters and sets from the game. With her ornate, colonial dresses and sets, 1770s Felicity could be a princess, with a boy in silk breeches as a prince. I read Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess and considered the 1995 adaptation one of my favorite movies. I “cast” Samantha Parkington, a wealthy, white girl circa 1904, as Burnett’s protagonist, Sara Crewe. Once I’d done that, “casting” Samantha’s friends and family as Sara’s dad Captain Crewe, the servant girl Becky, or headmistress Miss Minchin was easy. For obvious reasons, it was impossible to mix and match characters or sets from different eras, but it would have let me adapt many more stories.

The American Girls franchise provided me with many hours of reading and creative play—serious or hilarious. It helped me to empathize with fictional characters from diverse backgrounds. It also spurred my development as a writer who loves interpreting, reimagining, and responding to literature. I didn’t need any computer piracy or coding skills to “hack” the game from its intended use. I even recorded my own audio using my computer’s microphone. Years later, in high school and community musical theater, I still remembered my early obsession with sets, casts, and other elements of plays.

In 1997, I started third grade and was too young to learn about slavery in detail in school. However, I read about it in Connie Porter’s powerful Addy books. Of course, as a white kid in the 20th century, I could never understand how it felt to be enslaved. Although it was fictional and written for children, Addy’s series taught me about slaveowners brutalizing people and separating families in an individual way that school hadn’t yet. The series helped me read diversely, learn about people and experiences far beyond myself, and made me a lifelong historical fiction fan.

For Christmas, almost six months after I got my Kirsten doll, my parents bought me the computer game The American Girls Premiere. The game allowed players to create multiple-act plays starring the characters. We could select the main character, her supporting cast, sets, props, lighting, and more. Computer animation and AI from the ’90s would seem slow and clunky today. As my cousins and I typed dialogue, we realized that the robotic voice would speak in run-on sentences unless we punctuated them. We found it hilarious that it hadn’t been programmed to pronounce Addy’s friend M’Dear’s nickname correctly. We made each other laugh uproariously just by making the deadpan voice say, “Hell-O, EM-Deer!”

Once we learned that the game could be unintentionally funny, we started using it in ways the creators had probably never imagined. Why couldn’t a white man in a colonial, powdered wig solemnly recite nursery rhymes or ’90s song lyrics? We used keyboard commands to position characters, but they could also levitate, walk through walls, or spin in circles. We added the bear sound effect from Kirsten’s stories at random moments.

Soon, we got tired of our own attempts at absurdist humor or just recreating scenes from the books. I realized that I could basically write fan fiction by continuing the books’ stories. Obviously, I spent a lot of time joking with friends and reading, writing, and playing on my own.

I began creating my own literary adaptations, using the characters and sets from the game. With her ornate, colonial dresses and sets, 1770s Felicity could be a princess, with a boy in silk breeches as a prince. I read Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess and considered the 1995 adaptation one of my favorite movies. I “cast” Samantha Parkington, a wealthy, white girl circa 1904, as Burnett’s protagonist, Sara Crewe. Once I’d done that, “casting” Samantha’s friends and family as Sara’s dad Captain Crewe, the servant girl Becky, or headmistress Miss Minchin was easy. For obvious reasons, it was impossible to mix and match characters or sets from different eras, but it would have let me adapt many more stories.

The American Girls franchise provided me with many hours of reading and creative play—serious or hilarious. It helped me to empathize with fictional characters from diverse backgrounds. It also spurred my development as a writer who loves interpreting, reimagining, and responding to literature. I didn’t need any computer piracy or coding skills to “hack” the game from its intended use. I even recorded my own audio using my computer’s microphone. Years later, in high school and community musical theater, I still remembered my early obsession with sets, casts, and other elements of plays.