Reading Alice Austen, Lesbian Photographer

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

How quickly we forget artists from the past. How easily they slide from popular consciousness.

I only recently discovered Alice Austen (1866–1952), a photographer extraordinaire who loved a woman for half a century and was buried alone.* And I am infuriated to discover that despite her engaging life and art, very little has been published about her. The books I have found, I have to share.

Alice (baptized as Elizabeth Alice Munn) was born in New York City in 1866. Since Alice’s father left her family before she was born, Alice lived in her mother’s family’s house, the amiably named Clear Comfort, and went by her maternal surname, Austen. Living with her mother’s family gave Alice a gift: access to photography.

One uncle, Oswald Müller, brought home a camera, a gigantic piece of equipment back then. Another uncle, a Rutgers professor of chemistry named Peter Townsend Austen, taught Alice how to process her photos. After Alice’s love of the medium became apparent, the two uncles converted one of the household closets into a darkroom, and Alice made quick use of it. Her earliest surviving photo is from 1884, when she was 12 or 13. Over the course of her life, she took and printed approximately 8,000 photos. (Many of these can be found online at the Alice Austen House site and in Historic Richmond Town’s digital archive.)

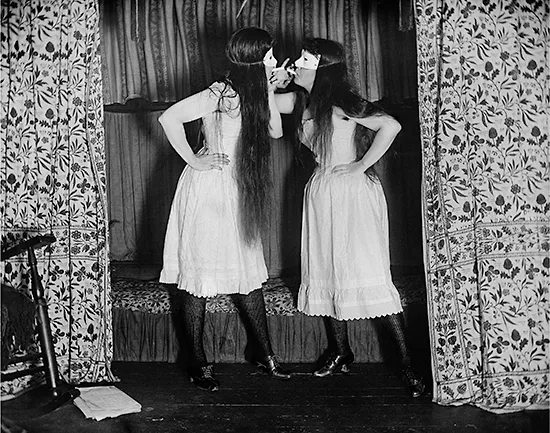

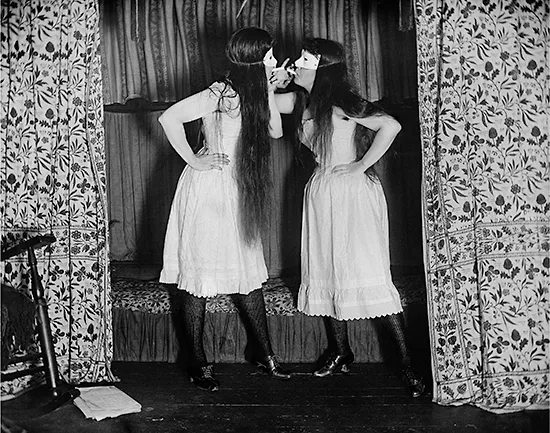

These photos revolve around daily life in New York City and the surrounding area. Upper-middle class people. The poor. Immigrant communities. Lesbians.

That last category, Alice’s photographs of women who were in romantic relationships with other women, are the most profound ones for me. They were also personal for Alice.

In 1899, Alice met the woman who would become her life partner: Gertrude Amelia Tate (1871–1962). Gertrude, who Alice sometimes referred to as “Trude,” taught both dance and kindergarten. The two women quickly fell into what Gertrude’s family described as a “wrong devotion”. Today we would say that the two fell in love. They visited regularly, traveled Europe together, and in 1917, Gertrude moved into Alice’s family home, Clear Comfort. For a while, all was well.

Then the U.S. economy crashed in 1929, and Alice’s main source of income, interest from an inheritance, disappeared. Suddenly Gertrude and Alice had very little money. They managed to survive for two decades by selling their furniture and other items. Then in 1945, the bank took Clear Comfort. To preserve them, Alice gave her photos to a friend who worked with the Staten Island Historical Society. She sold all of her remaining belongings.

But it wasn’t enough.

In 1950, Gertrude’s family offered to take her in. They would not, however, accept Alice. With nowhere else to go, 79-year-old Gertrude left, and the state declared 84-year-old Alice a pauper. Alice was sent to live out her days in Staten Island’s poorhouse.

Around this time, the world began to remember Alice Austen. Staff at the Staten Island Historical Society shared Alice’s images and negatives with Picture Press, journalist and author Oliver Jensen included her in his book Revolt of Women, and, most importantly, he published a story in Life magazine about Alice. From royalties for her work’s inclusion in these publication, Alice had just enough money to move out of the poorhouse and into a private nursing home.

But she never reunited with Gertrude. And when the pair died, Alice in 1952 and Gertrude in 1962, their respective families refused to allow them to be buried together.

Despite the fascinating nature of Alice’s life and her importance as an early photographer, there are relatively few publications about her. I have, however, pulled together a list of essential readings on Alice Austen. Some of these readings focus solely on Alice. Others include her among other women. All are fascinating. I only wish I had more to share.

After all, stories about women like Alice Austen remind us that LGBT individuals existed, built lives together, and loved, regardless of what their families thought. The way that access to money allowed Alice and Gertrude to be together and the loss of it tore them apart is likewise indicative of how class impacted LGBT lives.

In 1899, Alice met the woman who would become her life partner: Gertrude Amelia Tate (1871–1962). Gertrude, who Alice sometimes referred to as “Trude,” taught both dance and kindergarten. The two women quickly fell into what Gertrude’s family described as a “wrong devotion”. Today we would say that the two fell in love. They visited regularly, traveled Europe together, and in 1917, Gertrude moved into Alice’s family home, Clear Comfort. For a while, all was well.

Then the U.S. economy crashed in 1929, and Alice’s main source of income, interest from an inheritance, disappeared. Suddenly Gertrude and Alice had very little money. They managed to survive for two decades by selling their furniture and other items. Then in 1945, the bank took Clear Comfort. To preserve them, Alice gave her photos to a friend who worked with the Staten Island Historical Society. She sold all of her remaining belongings.

But it wasn’t enough.

In 1950, Gertrude’s family offered to take her in. They would not, however, accept Alice. With nowhere else to go, 79-year-old Gertrude left, and the state declared 84-year-old Alice a pauper. Alice was sent to live out her days in Staten Island’s poorhouse.

Around this time, the world began to remember Alice Austen. Staff at the Staten Island Historical Society shared Alice’s images and negatives with Picture Press, journalist and author Oliver Jensen included her in his book Revolt of Women, and, most importantly, he published a story in Life magazine about Alice. From royalties for her work’s inclusion in these publication, Alice had just enough money to move out of the poorhouse and into a private nursing home.

But she never reunited with Gertrude. And when the pair died, Alice in 1952 and Gertrude in 1962, their respective families refused to allow them to be buried together.

Despite the fascinating nature of Alice’s life and her importance as an early photographer, there are relatively few publications about her. I have, however, pulled together a list of essential readings on Alice Austen. Some of these readings focus solely on Alice. Others include her among other women. All are fascinating. I only wish I had more to share.

After all, stories about women like Alice Austen remind us that LGBT individuals existed, built lives together, and loved, regardless of what their families thought. The way that access to money allowed Alice and Gertrude to be together and the loss of it tore them apart is likewise indicative of how class impacted LGBT lives.

Amy Khoudari, Looking in the Shadows: The Life of Alice Austen

Oliver Jensen, The Revolt of American Women

Ann Nvotny, Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original: Alice Austen, 1866–1952

Jessica Loren Roscio, Unpacking a Victorian Woman: Alice Austen and Photography of the Cult of Domesticity in Nineteenth-Century America

And of course, you can peruse the excellent Alice Austen House website.

*I occasionally describe Alice as as a lesbian. That language is shorthand to describe Alice’s romantic and sexual entanglements with women. Though the 1890s–1930s saw the rise of women embracing the term, it is unclear whether Alice or her photographic subjects used it to describe themselves.

Amy Khoudari, Looking in the Shadows: The Life of Alice Austen

Oliver Jensen, The Revolt of American Women

Ann Nvotny, Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original: Alice Austen, 1866–1952

Jessica Loren Roscio, Unpacking a Victorian Woman: Alice Austen and Photography of the Cult of Domesticity in Nineteenth-Century America

And of course, you can peruse the excellent Alice Austen House website.

*I occasionally describe Alice as as a lesbian. That language is shorthand to describe Alice’s romantic and sexual entanglements with women. Though the 1890s–1930s saw the rise of women embracing the term, it is unclear whether Alice or her photographic subjects used it to describe themselves.

A picture taken by Alice Austen titled “Trude and I Masked”. From the Alice Austen Museum, now in public domain.

Reading Alice Austen

Amy Khoudari, Looking in the Shadows: The Life of Alice Austen

Oliver Jensen, The Revolt of American Women

Ann Nvotny, Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original: Alice Austen, 1866–1952

Jessica Loren Roscio, Unpacking a Victorian Woman: Alice Austen and Photography of the Cult of Domesticity in Nineteenth-Century America

And of course, you can peruse the excellent Alice Austen House website.

*I occasionally describe Alice as as a lesbian. That language is shorthand to describe Alice’s romantic and sexual entanglements with women. Though the 1890s–1930s saw the rise of women embracing the term, it is unclear whether Alice or her photographic subjects used it to describe themselves.

Amy Khoudari, Looking in the Shadows: The Life of Alice Austen

Oliver Jensen, The Revolt of American Women

Ann Nvotny, Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original: Alice Austen, 1866–1952

Jessica Loren Roscio, Unpacking a Victorian Woman: Alice Austen and Photography of the Cult of Domesticity in Nineteenth-Century America

And of course, you can peruse the excellent Alice Austen House website.

*I occasionally describe Alice as as a lesbian. That language is shorthand to describe Alice’s romantic and sexual entanglements with women. Though the 1890s–1930s saw the rise of women embracing the term, it is unclear whether Alice or her photographic subjects used it to describe themselves.