Anatomy of a Scene: The Many Endings of Carrie

One story. Three adaptations. Five different endings. How do you solve a problem like Carrie?

Mentioning Stephen King’s classic 1974 horror novel likely calls to mind one of two iconic scenes: Carrie getting her period for the first time in the school shower and being pelted with tampons as her classmates scream “Plug it up!” or Carrie wreaking fatal havoc on a gym full of students after being drenched in pig’s blood just as she was crowned prom queen. But King’s novel is more than just a pair of bloody bookends. King crafts a lean, chilling, and insightful story that has at its heart a pair of complicated teenage girls who resist easy characterization.

Carrie White is, famously, a victim of bullying and abuse, but in King’s hands she isn’t a “perfect” victim. She isn’t pretty. She isn’t smart. She doesn’t stand up for herself. And King is careful to show how much easier that makes it for people (and potentially even the reader) to marginalize her and to accept the brutal, dehumanizing treatment of her. King also ensures that Carrie isn’t an angel. When she is pushed to her breaking point, she doesn’t (as many film adaptations often suggest) go into a “trance” or react instinctively and without intention. Instead she very deliberately and maliciously destroys her town’s water supplies before dousing as much of it as possible it in gasoline and setting it on fire.

Sue Snell, Carrie’s sometime-bully, sometimes-ally, is also a complex character. Sue is alternately hostile and generous, and conformist and defiant but always acutely self-aware. Her motives are frequently mixed but she interrogates them more than any other character in King’s novel. She is complicit in bullying Carrie in the infamous shower scene and continues to think about Carrie in sometimes uncharitable terms (“she could take better care of herself she does look just like a GODDAMN TOAD”). To atone for her part in the bullying and to give Carrie at least one good memory of high school Sue gives her prom night with her boyfriend, Tommy, for Carrie, and risks provoking her classmates’ ire in the process. But even as she does this, Sue acknowledges her “sacrifice” is also a means of assuaging her guilt and exercising her power over Tommy.

Sue is disdainful of the future she very easily sees for herself, the same future as so many other girls like her: marrying her high school boyfriend, never leaving town, and joining the local country club. Ironically, despite her own desperate desire to fit in, it is Carrie who frees Sue from a life of stifling conformity. It’s Carrie who inspires Sue’s first transgressions against the social order: Sue rebels against the cruel, popular Chris Hargensen by accepting her share of the punishment for abusing Carrie and flouts the expectations of her peers by sending Carrie to prom in her place. And of course, Carrie’s actions on prom night obviously ensure Sue’s life will never be the same. The reader never learns if Sue Snell marries or joins a country club, but we do know that she wrote a book, a memoir of her account of what happened on prom night that both exonerates her from implication in Chris Hargensen’s horrific “prank” and humanizes Carrie.

Sue thinks about Carrie almost constantly throughout the novel, but the connection between Sue and Carrie comes to a head at the end. Sue is drawn to the high school by a strange sense of premonitory dread, suggesting a psychic link between the two girls. Although several witnesses describe being able to vaguely intuit Carrie’s feelings and intentions, Sue is the only character who is so in tune with Carrie she is actually able to track her. Most significantly, Sue is the only person who willingly opens her mind to Carrie. In the final scene of Carrie’s story, Sue finds a wounded, dying Carrie on the road after Carrie has killed her own mother and her tormentors, Chris and Billy. Sue is instinctively able to communicate telepathically with Carrie: “(who’s there) And Sue, without thought, spoke in the same fashion: (me sue snell).”

When Carrie accuses Sue of trying to trick her and forces Sue to experience the depth of Carrie’s pain and misery, Sue offers her mind up to be read: “(look carrie look inside me).” Carrie sees ugliness in Sue but some goodness, too; she sees that Sue never intended to hurt her. Most importantly, the two see each other. A bond, however conflicted and short-lived, forged between the pair. As Carrie dies Sue is able to offer company and the comfort of knowing at least one person meant her no harm. The final paragraph reinforces the connection between Carrie and Sue by mirroring the novel’s opening trauma, only this time it is Sue who feels blood run down her legs.

It’s a quiet, intense scene of reckoning and recognition, one that all three adaptations of King’s novel have diverged from pretty widely in different ways.

Brian de Palma’s 1976 film is is the first, most famous, and most widely-praised adaptation of Carrie. It’s a relatively faithful adaptation of King’s story (at least for the first two-thirds) that focuses entirely on Carrie’s story as it unfolds, eschewing the epistolary aspect of the novel – the interviews, textbook excerpts and reports that provide meta-commentary on the events of prom night.

De Palma’s film also reduces the role Sue plays in the story and the depth of her characterization. In de Palma’s version of the story, Sue is locked out of the gymnasium just before the bucket of blood drops and does not appear again on screen until after Carrie is dead. It’s a significant alteration. In a story steeped in the horrific feminine – from Margaret White’s sexualized abuse to Chris Hargensen’s vicious bullying to the bloody terror Carrie wreaks on the town – Sue and her last-minute vulnerability to Carrie is one of the few examples of imperfect, but ultimately compassionate womanhood the story offers has to offer.

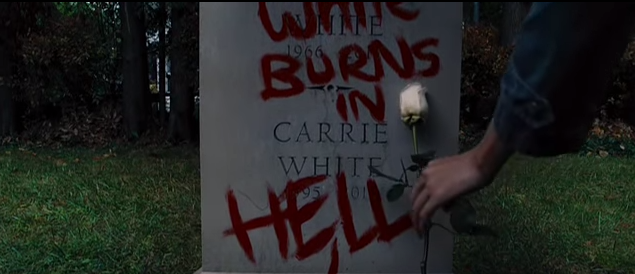

The final scene of de Palma’s film begins with Sue’s mother talking on the phone about Sue’s slow recovery from the trauma of prom night. The camera pans toward Sue sleeping on a makeshift bed in the living room and then fades into a misty dream sequence (famously made eerie by being filmed backward and then reversed to play forward in editing). In this dream Sue dressed in a white flowing gown and holding a colourful bouquet of flowers, walks toward the site of the former White house, where “Carrie White burns in hell” is scrawled in red paint across a For Sale sign.

Sue kneels down to lay the bouquet at the foot of the sign, when suddenly a bloody hand springs up from the earth and locks onto Sue’s wrist.

Sue screams, jolting the viewer back to reality and to Sue’s living room, where she is writhing and wailing while clutching at her wrist.

With her flowing white gown and colourful bouquet, Sue appears more bridal than funereal, but any implication of an eternal connection between the two girls seems at odds with the way de Palma underplayed Sue throughout the rest of the film. The most literal, clumsy interpretation would be that Sue is now “wedded” to her trauma of that night. Perhaps a better lens through which to view this moment would be Gothic horror, in which Sue represents not a bride per se, but a proto-Final Girl: a beautiful, vulnerable maiden imprisoned by a monster.

This interpretation is supported by de Palma’s comments that the final scene of his film was inspired by the 1972 thriller Deliverance. In the end of Deliverance, the protagonist is jolted awake by a nightmare of the sadistic cannibal strangers who hunted him throughout the film. By ending with this reference de Palma aligns Carrie with these psychopaths, recasts Carrie simply as a creature haunting Sue’s unconscious. It’s a striking ending that is consistent with both genre tropes and de Palma’s specific vision for Carrie, but not the character of Sue Snell or her relationship with Carrie.

Kimberley Pierce’s 2013 adaptation of Carrie had a famously troubled production and post-production. Pierce’s original aim was to to be a reinterpretation of King’s novel; there are rumoured to be 40 minutes of cut footage, including filmed versions of many of the White Commission. The film that resulted after excessive studio tinkering is much closer to de Palma’s movie than King’s novel. Critics panned the Pierce’s adaptation and called it “unnecessary” given its similarity to the still-iconic de Palma film. Where Pierce’s film does diverge from de Palma’s somewhat is in its restoration of Sue as a main character.

The version of Sue in this film is a slightly smoothed-out version of King’s character – not quite as cruel or derisive in her worst moments – but Pierce does maintain Sue’s complexity and the connection between her and Carrie. Sue’s insecurities and internal conflicts are verbalized and mirrored back to her in a scene with the cruelly perceptive Chris. In Pierce’s adaption, Sue does find Carrie at the end of the latter’s reign of terror; she tries to help Carrie out of the rapidly disintegrating house and pull her to safety. Carrie finally understands that Sue did not intend to trick her. And while Carrie doesn’t read Sue’s mind in this adaptation, she does look into her body: Carrie gets one final, genuine smile when she tells Sue that she is pregnant with a girl (this pregnancy is another restoration, of sorts, from the novel: after Carrie has agrees to be Tommy’s date, Sue realizes her period is late and worries she might be pregnant. Sue gets her period in the final paragraph).

In the final scene of Pierce’s theatrical cut, Sue is interviewed by an investigative committee, the only extant footage of the White Commission. A man patronizingly tells Sue that she was under an enormous amount of stress and asks if it’s possible that what she witnessed was a natural act? Sue remains firm. She acknowledges that yes, her boyfriend and all of her friends died that night, but she knows what she saw.

The scene then shifts to a rainy graveyard, where a black-clad Sue is walking with a single white rose in her hand. Sue’s testimony from the hearing continues in voiceover: “You want an explanation? Carrie had some kind of power. But she was just like me. Like any of you. She had hopes and she had fears. And we pushed her. But you can only push someone so far. Before they break.”

The words “Carrie White burns in hell” appear again here, this time scrawled in red paint across Carrie’s actual gravestone. Sue lays down her rose. The camera stays on the gravestone as Sue’s black-booted feet walk away and an electric guitar riff starts up. Once Sue passes, the music builds, nearby fallen leaves begin to levitate in the air, and, with the sound of a scream, Carrie’s headstone cracks.

It’s not an entirely faithful adaptation of the original end of Carrie, but for the most part it is consistent with the spirit of King’s ending. It establishes a connection between the two girls and gives Sue a voice to tell their stories. It’s after this point that things take a turn for the nonsensical. Unlike in de Palma’s film, there is no indication that the gravestone shattering moment exists in the context a dream: Sue doesn’t even see the stone shatter, only the audience does. Actually, it’s worth noting Carrie spares Sue that fright. If we accept that Carrie has suddenly become a ghost, we can be reasonably sure she isn’t haunting Sue. And ghost-Carrie does seem like the most obvious interpretation – if we take this moment literally and as integral to the film. Frankly, though, it reads less like a thoughtful addition to the rest of the film and more like a half-hearted capitulation to the genre dictate to end on a scare.

It’s also not Pierce’s original ending. When Carrie was released on Blu-Ray, it came with an alternate ending, one of the few pieces of cut footage released to the public. In this ending, there is no investigative hearing and no voiceover explaining the reasons behind Carrie’s “break.” Sue still places the flower on the grave but this time, she reaches for her (obviously pregnant) belly and screams in pain.

The scene flashes to one of her in the delivery room, still screaming, and asking again and again “Is this normal?” as objects begin to fly around the room. Suddenly, a bloody hand emerges from between Sue’s legs. Sue screams and then briefly sees an image of a blood-soaked Carrie cradling her infant. There is another cut to Sue’s bedroom where this everything that preceded is revealed to be a dream. Sue is still pregnant and clutches her belly, still screaming, as her mother holds her hand.

Ironically while the rest of the cut footage was rumoured to me much more consistent with King’s novel, this ending borrows significantly from de Palma’s film, with Pierce doing him one better on the shock front – after all, what’s more horrifying that someone haunting you from beyond the grave? Her haunting you from inside your own body. This ending sits a lot more strangely with the rest of Pierce’s film because it seems to undermine the connection established between Sue and Carrie at Carrie’s death by ending on a note of fear. However it’s worth noting that this fear is not of Carrie herself, but of giving birth to Carrie: of having a daughter that takes after (the tormented, suffering and eventually violent) Carrie.

The 2002 made-for-television adaptation of Carrie offers another ending for the story that differs dramatically from the novel and the film adaptations and for good reason. In screenwriter Bryan Fuller and director David Carson’s adaptation, no one gets haunted by Carrie, either literally or figuratively, because Carrie doesn’t die. This adaptation was intended as a backdoor pilot for an ongoing Carrie television series (it wasn’t picked up).

In this version, Sue comes to Carrie’s rescue and resuscitate her after Margaret tries to drown her. In Carson’s version, it is while Sue is literally breathing the life back into Carrie that she sees inside her head. Sue convinces Carrie to fake her own death and, as the audience learns via intercut interviews with the police, lies for her.

Then Carson gets his version of the de Palma ending with a cut to a graveyard, where Sue and a disguised, bewigged Carrie stand in front of Margaret’s tombstone. Sue tells Carrie to go somewhere no one knows her and offers to drive her as far as Florida.

As Sue walks away, Carrie feels a hand clap her on the shoulder. Suddenly Margaret is standing behind her, croaking “sin never dies.” Carrie jolts awake and finds herself in Sue’s car. “Bad dream?” Sue asks, before her face is transformed into that of Chris Hargensen. Carrie snaps out of that hallucination, then pulls of her wig and stars pensively into the distance.

This adaptation of Carrie maintains Sue’s prominence and the connection between the two, but makes both more palatable, comfortable characters. In an interview, Bryan Fuller described his Carrie as “edgy” but “sweet” and neither a victim nor a murderer. And the end Sue is a much more straightforward friend to Carrie, with their mad dash across state lines evoking shades of Thelma and Louise. This ending is a significant departure from all previous version of the characters, which makes sense for a film exists not so much to adapt King’s book but to provide an origin story for a new series. Margaret White and Chris Hargensen take the role Carrie occupies at the end of the other adaptations with Carrie essentially taking on Sue’s role. In this version, Carrie gets to be the Final Girl. Her story is just beginning.

**********

These various adapted endings all have their points of interest but it’s hard to argue with King’s original. It’s incredibly satisfying: poignant but not too pat. Sue and Carrie overcome social barriers and forge a brief but powerful and utterly honest connection. Sue is forced to truly bear witness to the pain Carrie has suffered and gets the opportunity to offer Carrie a moment’s succor with no ulterior motives. Carrie gets a measure of peace, dying knowing that at least someone didn’t mean to hurt her. So what is it about King’s ending that filmmakers consistently shy away from, no matter how faithfully they adapt the rest of his novel?

Short of a “Carrie adapters’ roundtable,” we can never really be sure. The easiest answer might be in the question: King’s ending is highly novelistic. It is a scene comprised of telepathic communication. It happens almost entirely inside a teenage girl’s head, a place we know Hollywood is often reluctant to go. But films have represented and adapted wordless communication in a variety of interesting, effective ways. Interiority is not the provenance of the novel alone.

Stories change in the telling, though, and as they do, so do endings. The story of Carrie, has been enshrined in pop culture as a fairly straightforward horror story, a quite literal bloodbath. The horror most strongly associated with Carrie is gore, the horror of mass murders and pig’s blood. This kind of horror story suits a spooky or bloody twist ending; it may even demand one.

But at its heart Carrie is a horror story of isolation and abuse about a girl with no safe haven and no one to understand her. It’s about the horror of being alone in the dark. And the shock ending of King’s novel is that – just for a moment and far too late – she isn’t.