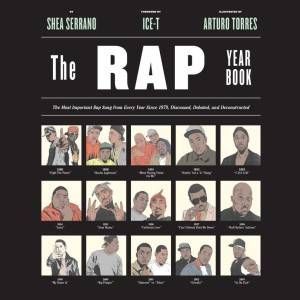

THE RAP YEAR BOOK and Twitter’s Best-Seller Magic

Shea Serrano is a writer for Grantland (or was until, in the middle of me writing this piece, ESPN unceremoniously shuttered it), the author of Bun B’s Rapper Coloring and Activity Book (which is exactly what it sounds like), a former high school teacher, and – I’m thoroughly convinced – a mad genius.

Let me explain.

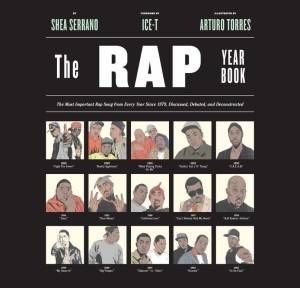

Last February, the sales page for Serrano’s (as-then-yet unfinished) The Rap Year Book, in which the most important rap song from every year 1979 – 2014 is dissected by the author, innocuously went live on Amazon. A short time later, one of Serrano’s Twitter followers sent him a screen shot of his preorder of the book. It’s the sort of thing that happens all the time in the social media age. The distance between authors and readers, fans and the sources of their fandom, is shorter than ever. Still, in most cases, the tweeted screenshot would’ve been as far as it went.

Instead, over the intervening months, that scene played itself out over and over and over again. As the book’s October release date approached, it was happening dozens of times a day. People were buying the book for themselves and their friends, buying multiple copies just because, buying the Kindle edition to read while they waited for their hard copy to arrive. One woman bought a dozen copies and gave them away to random Twitter followers.

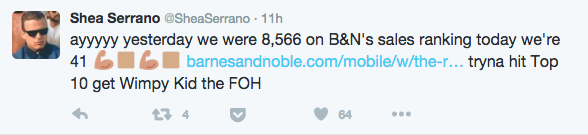

By the time the book released, Amazon was sold out. Barnes and Noble sold out soon after. Books-a-Million followed suit.

None of this happened because The Rap Year Book got a bunch of great pre-release press or because of a marketing blitz from the publisher. As best I can tell, it happened almost entirely because of Serrano himself. Few writers have developed the kind of fan connection on social media that he has, and I don’t just mean that he has a lot of followers or that those followers like him a lot. He does (43.1K Twitter followers as of this writing), and they do, but the secret ingredient, the thing that caused thousands of people to buy out The Rap Year Book at three of the largest book retailers in the world and force the publisher to print more copies, is the level to which Serrano has involved his followers in the story of his own burgeoning success as a writer.

This is the mad genius bit.

Shea Serrano is a killer follow on Twitter. You know how when most people tweet about their kids, it’s mostly exhausting? Here’s Serrano about his boys:

Ok, so I don’t know if that tweet actually happened, but it’s a perfect example of how Serrano has mastered the limits of 140 characters. He treats the medium like a standup comic treats the stage: as a place fit for a persona that takes his real personality and interests, and tweaks it in all the right places to form a compelling voice.

Here’s a random tweet I screengrabbed while writing this:

This one’s about par the course, capitalization-and-punctuation-wise, but it’s also a pretty perfect encapsulation of the persona Serrano has created, plus it has a Drake reference. It’s pretty much his whole feed in a nutshell, is what I’m saying.

If it sounds like I’m fawning, I guess I am. But that’s actually kind of my point about Serrano and The Rap Year Book. He’s funny, yes, but he’s also warm and inclusive and profuse in the thanks and amazement he’s been expressing as it has become increasingly clear that his book isn’t just going to be successful, but massively so. I honestly think the people who were preordering his book by the dozens were doing so largely because they liked Serrano as a person, even though the only real contact they’d had with him was through his writing on Grantland and on Twitter. Obviously, it was more than enough. I mean, you should see how many people note that they don’t really like or listen to rap music when they let Serrano know they’ve purchased his book. They’re rooting for him, first and foremost.

Clearly, I’m impressed with the dude. I preordered The Rap Year Book myself back in September, and after I saw that it had sold out at basically every online book retailer, I reached out to Serrano to ask if he’d be up for talking with me about the whole crazy series of events and how he was processing it all. He emailed me back in four minutes, said yes, and left me his phone number. When I texted him later to set up a time for the call, he addressed me as “homie.” He did it again when he answered my call during Monday Night Football, which Serrano was watching from his hotel in L.A. during a brief book tour, during which The Rap Year Book had sold out of every store at which the author stopped.

For the record, nobody’s ever called me “homie” in my life. I’m the kind of white dude Chris Rock and Dave Chappelle joke about in their stand-up sets – doofy and awkward and square – not exactly homie material. But Serrano made me feel included and cool and as I talked to him it was even more apparent why The Rap Year Book was blowing up: his writing does exactly the same thing.

As for the book itself, I assumed that it was a long-gestating passion project, the kind of thing that any list-making music geek would kill to publish. Not so. “I didn’t have any ideas for whatever book I was gonna do next,” Serrano told me. His editor suggested writing about the most important rap songs from every year since the music first became popularized. Serrano’s response?

“That sounds awful – I don’t want to do that. At all. I mean, I like rap, but I don’t wanna read about fuckin’ Afrika Bambaataa. That’s just not a thing I’m into.”

Strike one for my readerly instincts, I guess. But here we are all this time later and the book is not only published, but it’s hit the New York Times Best Seller List. So what changed? Serrano: “A couple months later, my wife decided we needed to move into a house. We were living in a townhome at the time with three kids – we’d just had the baby. That means we needed a down payment. Suddenly, that book didn’t seem like such a bad idea after all.”

Though Serrano isn’t the music list-making fiend I imagined him to be while reading The Rap Year Book, there are some aspects of them he won’t deny: “Lists are just fun, and they always inspire some sort of conversation.”

It’s undeniable that both of these points inform a huge portion of what exists between the covers of The Rap Year Book. Each essay is written with Serrano’s combination of deadpan humor (sample line: “Could you ever even imagine one single other rap superstar blowing into Lance Stephenson’s ear, or that of any player from the Charlotte Hornets, for that matter. No, you cannot. Only Drake.”) and incisive smarts (another sample line: “The best version of rap is the self-aware one (or the self-reflective one). That’s why gangsta rap was crucial early on (it drew from the crack plague), and G-Funk (it drew from the tempering and normalization of inner-city strife), and big money music (it drew from rap’s own success), etc.”) and all of them include an annotated infographic that maps the song’s most notable lyrics to a key of thematic symbols. Sorry for all those parentheses, but that gives you a sense of just how much goodness is packed into each one of these 25 essays.

And that’s not even including the rebuttals that end each chapter. See, Serrano plays dictator by making the decision about which song from each year deserves the title of “most important,” but then he leaves room from other writers to have their say and offer up alternative choices. In that way, the book is much more about starting conversations than issuing definitive judgments. Serrano knows that his appraisals are almost entirely subjective, and he backs up his openness to debate by actually letting happen within the pages of his book.

So subjective are some of the chapters, in fact, that the entries occasionally read more like personal narratives that analytical breakdowns. The sometimes highly personal stories that make their way into the “Fight the Power” (1989) and “La Di Da Di” (1985) chapters stand out especially clearly even a couple of weeks after I’ve finished the book. I asked Serrano how he made the choice to include these anecdotes in a book which otherwise spends most of its time living in the music itself (or making jokes about it). He notes that the nature of music means that we can’t help treating it like it’s about us in some ways. “If I talk about a song, then chances are I’m gonna end up telling a story about something that happened [to me]. There are moments tied to songs. That’s what happens with music.”

The stories, though, are another instance of that openness that seems to mark Serrano’s writing, his internet persona, and his actual self. Actually, I’m pretty sure that if you made a Venn diagram of those three things, they’d overlap each other by about 90%. It makes him seem transparent in a way that so few other writers – even those with niche audiences – do. It adds up to likeability or some whatever-you-wanna-call-it that makes it hard not to be on his side. And the pattern that’s created a best seller almost from thin air keeps getting clearer.

Well, for somebody on the outside, maybe. For Serrano, it was a little less cut and dried. “It was weird while it was happening. It was exciting, but there was a moment when I sat there wondering, ‘Why did this happen? What did I do differently?'”

I put forth another theory, this time explaining that I see his approachability and his eagerness to interact with his Twitter followers as the magical pixie dust that sent the book soaring. Serrano agrees, and I avoid going 0 for 2. “On the strength of me putting the Amazon link on Twitter one time, the book went to number one in the “Rap Books” section or whatever. Which isn’t that hard to do, but right then I went, ‘They hadn’t seen the book, so they’re ordering it because they like me, not because they like the book.’ With the coloring book, I was really worried about getting into Rolling Stone or the L.A. Times, but with this one, I didn’t worry about any of that. I was just doing these hand-to-hand kind of transactions. Like selling out of the trunk of a car or something, like real rap stuff, you know what I’m saying?”

Unsurprisingly, a rap metaphor turns out to be the perfect explanation of The Rap Year Book‘s rapid ascent. Like a hot underground mixtape, this book was being passed around in huge numbers on the strength of a few sample performances by a handful of passionate, supportive people who found something that spoke to them.

It helps a whole lot that the book itself works on just about every level. It’s a history of hip-hop, a worthy introduction into the entire genre, a compelling series of well-supported arguments, and a thorough evaluation of everything that makes rap music so essential to the broader musical landscape.

As of this writing, The Rap Year Book is #300 on Amazon’s best selling books list, hurt, I’m sure, by the fact that it’s currently out of stock. It’s in its third printing. Shea Serrano keeps getting tweets from people who have either ordered or received their copies. I sometimes wonder when the train is going to stop and when The Rap Year Book is going to come back to earth. Then I check Twitter and see this:

That’s when I realize this thing’s never coming down.

And that makes me smile.