How a Polish Punk Cartoonist Became a Union Organizer in Sweden

Wage Slaves is part call to arms and part migrant memoir. The comic, by Daria Bogdanksa, recounts her move to Malmö, Sweden after bopping around several other European countries. She navigates adjusting to a new home while dealing with ambiguous romantic relationships, immigration issues, and – in the core of the book – challenging the erosion of her rights at work.

One of the dead-end jobs that Bogdanksa takes on is waiting tables at an Indian restaurant called Curry Hut. The employees work up to 15 hours a day for little pay, without contracts, under poor conditions including a lack of ventilation. They stay out of desperation and dependency; many are migrants from Bangladesh who depend on the restaurant’s owner for housing, visas, or debt repayment. Some are also physically threatened. Bogdanska herself, during the height of the workplace tensions, has a friend pick her up from work, out of apprehension.

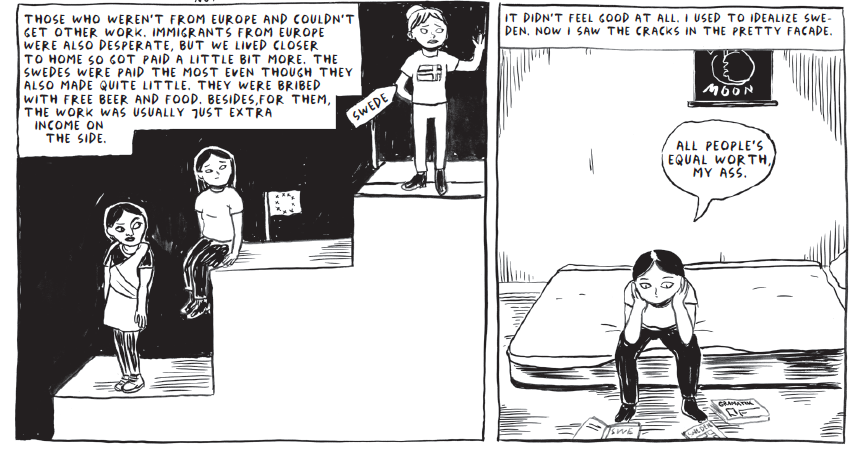

She recognizes that she, a Pole, is more privileged than the Bangladeshi migrants who speak even less Swedish than her, though she’s less fortunate than the Swedes who work in the restaurant for pocket money. And the restaurant’s owner has put these distinctions into practice, essentially paying employees more based on how white and local they are.

After connecting with others in the labor rights movement and learning a great deal about unionizing, Bogdanska attempts to organize the employees. Ultimately, it’s a mixed victory. She gets paid the money she’s owed, but the other workers don’t.

This experience was “bittersweet,” Bogdanska says now, soon after the publication of the English translation of her graphic memoir (three years after it was first published in Swedish). “I wanted conflict but nothing really changed.” A win for herself only didn’t feel like much of a win.

“Everybody likes a story with a happy ending,” she comments wryly. Plenty of Swedish media attention accompanied her labor battle and the book’s publication, and the book was well-received apart from some hate mail sent by racists.

Yet Curry Hut, the main site of the labor violations Bogdanska documents, is still operating. She doesn’t know what to say to well-meaning readers in the left-leaning neighborhood of Mollan who ask her anxiously where they can eat with a clear conscience. “I don’t know. I’m not perfect either,” she stresses. She can’t be sure that the cheap falafel place she frequents are respecting workers’ rights.

But Bogdanska isn’t cynical, and she believes that consumer action is ultimately less significant than action by the people who are most affected: the workers themselves. Since the book was published, she’s taught cartooning and played in a punk band. She also negotiates workplace conflicts with the union SAC, where she works primarily with female migrants, often cleaners. She says, “My frustration, I put into helping other people organize.”

This frustration includes what Bogdanska sees as the hidebound practices of unions that have been slow to modernize, even though their traditions may make them less relevant to groups like migrant workers, for instance. “Unions are more like insurance companies today,” treating workers more like customers than a potent political force, she believes. This drives her: “I hope for some kind of union revival.” So does the satisfaction of seeing successful settlements and court cases following her negotiation group’s discussions with employers.

Bogdanska is now preparing to study labor law. “As a 31-year-old, I will finally go to university,” the self-described high school dropout says with a laugh. She’s also working on her next graphic memoir, an ambitious look at the precarity in her own life (including her relationship with her alcoholic father) and the economic and relational precarity of her generation (she’s irritated by the media’s perpetuation of the “spoiled millennial” myth).