A Q&A With Authors Francisco X. Stork & Andrew Simonet

Francisco X. Stork and Andrew Simonet are fans of each other’s work, and met this October in Austin for the Texas Book Festival. In the conversation you’re about to read between them, they discuss writing for teens, YA coming of age stories, education’s role in literature, changing career paths and the differences between writing your first book vs. your seventh.

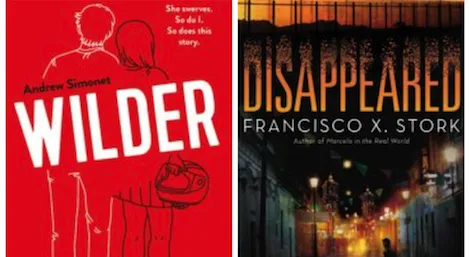

Francisco X. Stork came to El Paso from Mexico when he was nine-years old. He has an M.A from Harvard University and a J.D from Columbia University. He worked as an attorney for thirty-three years while writing seven novels, including Marcelo in the Real World, recipient of the Schneider Award; The Last Summer of the Death Warriors, recipient of the Elizabeth Walden Award; The Memory of Light, recipient of the Tomás Rivera Award. His latest novel Disappeared is the 2018 recipient of the Young Adult Award from the Texas Institute of Letters and a Walter Dean Myers Award Honor Book.

Francisco X. Stork came to El Paso from Mexico when he was nine-years old. He has an M.A from Harvard University and a J.D from Columbia University. He worked as an attorney for thirty-three years while writing seven novels, including Marcelo in the Real World, recipient of the Schneider Award; The Last Summer of the Death Warriors, recipient of the Elizabeth Walden Award; The Memory of Light, recipient of the Tomás Rivera Award. His latest novel Disappeared is the 2018 recipient of the Young Adult Award from the Texas Institute of Letters and a Walter Dean Myers Award Honor Book.

Francisco has been mentioned before in Book Riot’s list of Mental Health Books to add to your reading list!

Andrew Simonet is a choreographer and YA writer in Philadelphia. He co-directed Headlong Dance Theater for twenty years and founded Artists U, an incubator for helping artists make sustainable lives. He lives in West Philly with his wife, Elizabeth, and their two sons, Jesse Tiger and Nico Wolf. His debut novel, Wilder, is about passion, anger, secrets, and what happens when two teens from different worlds meet in in-school suspension.

Andrew Simonet is a choreographer and YA writer in Philadelphia. He co-directed Headlong Dance Theater for twenty years and founded Artists U, an incubator for helping artists make sustainable lives. He lives in West Philly with his wife, Elizabeth, and their two sons, Jesse Tiger and Nico Wolf. His debut novel, Wilder, is about passion, anger, secrets, and what happens when two teens from different worlds meet in in-school suspension.

Francisco X. Stork: Why do you write and why did you write Wilder?

Andrew Simonet: I write because it’s difficult. Like raising a child, like building a community, it pushes me up against big, spiritual challenges.

I write because I am fascinated (meaning obsessed (meaning wounded)) by the difference between being inside my mind and body and being inside yours. As a young person, it terrified me, the thought that I was somehow different, marked. I write in the faith this is an experience we all share, the dread that we are fundamentally set apart.

I write because I spent 20 years in a disappearing art form, an art of the moment. Dance brings you these bodies in this room right now. Writing is frighteningly, blessedly indelible.

I write because there are stories I need (and needed) as a man, a white man, an American man who has never felt 100% manly.

I write in the hope that sharing tiny truths can make us kinder to ourselves and to others.

I write because I fear the power of language to reduce and simplify. Writing is the crowbar I wedge under the slamming garage door of words.

I write to my younger self, to my sons, and to my future self.

I write to smash through my own smugness, my pat assumptions about my characters and their worlds.

I write because I get to choose the problems I work on, which means the problems interest me.

This novel, Wilder, showed up, is how I’d describe it. But it wasn’t honest with me. It took two years of writing to get past the deception, past the narrator’s story about himself. I wrote Wilder to untangle my own myths and deceits, the stories I tell myself as a man that justify my outrage, my anger, my righteousness. I wrote to peel back the layers scabbed over these male wounds, aggression covering anger covering hurt covering an aching need to be loved and seen.

This novel, Wilder, showed up, is how I’d describe it. But it wasn’t honest with me. It took two years of writing to get past the deception, past the narrator’s story about himself. I wrote Wilder to untangle my own myths and deceits, the stories I tell myself as a man that justify my outrage, my anger, my righteousness. I wrote to peel back the layers scabbed over these male wounds, aggression covering anger covering hurt covering an aching need to be loved and seen.

And I wrote Wilder to find the rhythm of Jason and Meili, the jagged and crackling song in their connection. Like many young people, they are mostly left to raise themselves, and each other, and that’s hard as hell. Their love is a song of ruthless generosity and bravery for those kids, those survivors, a song I could have used as a young man.

Can I turn your questions around? Why do you write? And why did you write Disappeared?

Francisco: I think your answer gave words to feelings for which I had no words. I often think that the best answer to the “why” question was Flannery O’Connor’s: Because it hurts worse when I don’t. There is this urge to create something new that we all have and carry inside of us. For some it is gardening or knitting sweaters or making a chair – but if we listen carefully it is inside all of us. For me, the urge seeks to manifest itself in the creation of characters and their stories. But this urge is so powerful that it will find a way to come out if not expressed. For me, depression and sometimes addiction has been the thwarted expression of the creative urge. It is also as you say, a question of sharing a gift with others. For the nature of a gift is that it be given. Disappeared was a way for me to write in a complex (which is to say realistic) way about Mexicans and the Mexican immigrant. But personally, it was a novel that transformed personal anger into love, which is, I think, what good art does.

Andrew: Anger into love! The alchemy of art making. And yes, the thwarted urge to create is treacherous. When I cannot write (or when I finish something), it feels like loved ones I’m not allowed to see.

Andrew: Anger into love! The alchemy of art making. And yes, the thwarted urge to create is treacherous. When I cannot write (or when I finish something), it feels like loved ones I’m not allowed to see.

Francisco: Tell me about Jason and Meili. They are amazing characters, both typical teenagers but also uniquely different. Have you figured out where they came from- what part of your life was the soil for their birth and growth?

Andrew: I’m not Jason, but he has parts of me. Unlike him, I hated the economy of fighting and respect I was expected to participate in. I tried hard to opt out and mostly did by the time I was a teenager. When fights did happen—like my first ridiculous fight which I’ll tell you about some time—I felt out of control, flooded by a fury that alarmed me, scared not just of getting hurt but of hurting someone.

I was mostly raised by my father, and there were times, after his second divorce, after my stepmother and half-sister moved out, when I was mostly raising myself. My close friend wrote me a poem then (young men writing each other poems!) that pictured me standing alone at my stove, cooking myself oatmeal in an empty house. It frightened me: Wait, how did you know? But I also felt seen in the most loving and honest way. That moment went more or less directly into the novel.

Certain aspects of Meili came from teaching dance at a private school with many students from overseas—China, India, the Middle East, Mexico, the Caribbean. Many, not all, came from considerable wealth. And, like Meili, some resented being sent away by their families. I loved hearing their take on America, which to them was a hilarious, sometimes bothersome, and often perplexing place. Their mix of humor, privilege, insight, and displacement lives in Meili.

I am curious about Sara, a writer and a detective of sorts. Where did she come from? How does her journey (telling the stories of the disappeared, refusing to forget or look away) connect to yours in writing Disappeared?

Francisco: Sara started out with a real Sara: A long-time friend who lives in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. The real Sara is not a reporter. She is a woman living in a very difficult place for women to live. In developing the fictional Sara’s character, it helped me to have a real example of the kind of courage that ordinary people who live in bad places have and how they manage to live their lives with kindness and purpose. The Sara in the book is also an ideal inside of me of a person with a solid, unwavering moral compass. It’s always good to have one or two characters that pull us in the right direction!

Tell me one hope and one fear that you have for this book.

Andrew: I fear people might sensationalize aspects of Wilder—the fights, the sexuality—and miss the heart of the story.

I hope to be in conversations with young men (and others) about masculinity, and how we men do the work of listening, opening, and reflecting.