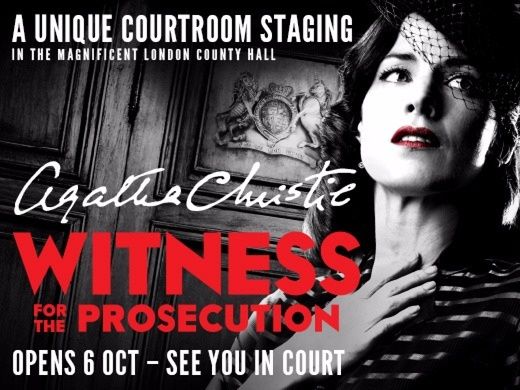

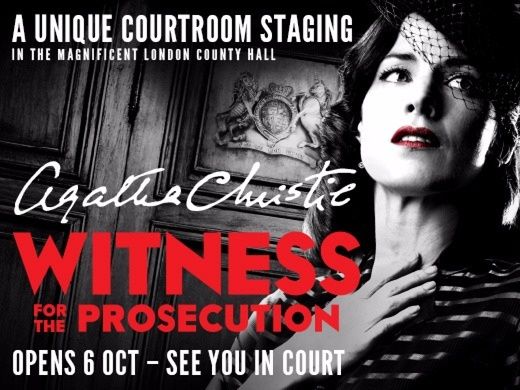

Reliving Agatha Christie at WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION

I’m a child of the ’90s—when I was growing up, it was all about the Spice Girls, Titanic, Y2K and Friends. Agatha Christie wasn’t even a consideration when it came to books, because Harry Potter had arrived and we were all busy with our Furbies. I read Agatha Christie for the first time when I was 22 years old and discovered And Then There Were None, one of the bestselling books of all time.

And Then There Were None is a child of its time—racist references and pejorative terms pervade the earlier versions of the text and even in the 2000s, the writing feels old. In the 1930s and ’40s, reviews lauded the originality and genius of Christie, who was prone to surprise endings, plot twists, and intrigue. For a child of the ’90s, where amazing twists and turns are par for the course, Christie can seem old-fashioned—until you realise that plot twists were the wheel she invented and perfected in pursuit of her craft.

Living in London, it seems a shame to not see more of Christie’s work, given that The Moustrap has been on stage here since 1952. When Kenneth Branagh’s Poirot took to the screen in 2017 in Murder on the Orient Express, I went to see it in Leicester Square. Neither item breaks the mould of modern cinema or theatre, but there’s no denying that Christie’s stories pull even the most contemporary reader in. Her plots are where the crime genre became a kingmaker, with intelligent storylines and a mass appeal—especially in the UK, where many stories were serialised in newspapers over a period of weeks or even months. It’s hard to imagine the excitement people might have had for the next snippet—not unlike today’s fandoms when a film trailer everyone has waited ages for pops onto a screen. Star Wars, anyone?

Most recently, London County Hall has been staging Witness for the Prosecution in the old Council Chamber. The venue is a beauty; opened by the royal family in 1922, London County Hall was the home of Lonodn government for many years. The marble staircases, public galleries and high ceilings are of a different time.

Witness for the Prosecution follows the tale of Leonard Vole, a young man accused of the murder of the elderly Emily French in London. Vole’s wife Romaine agrees to give evidence, but rather than give evidence for her husband, she becomes the titular witness for the prosecution. The story was first published in the 1920s and later appeared in collections in the UK and the U.S. Its late-in-the-day plot twist is legendary, though Christie herself later added a small fraction to it, as she was unhappy with it.

As with every time I read Christie, I invested in the play by envisioning what it must have been like in the 1920s, when the world was simpler and less dark. The play has some jokes that remain funny to this day, and even though the plot is quite linear by contrast with something like Gone Girl, the watcher is still left questioning each character’s motivations and commitments: is Vole naïve or a murderer? Does his wife love him, or does she loathe him? What of the murdered woman, at points referred to as competent and at others referred to as struggling? In the game of a trial, what does it mean to win or lose?

The setting is incredibly helpful for this viewing of Witness for the Prosecution. It looks and feels like a court room, right down to the judge’s chair and the gavel. The stage is set up in the space between the council chairs, and the overhanging public galleries are full of people gazing down in judgement of young Vole. The set is dressed sporadically by people passing through, carrying lamps, tables, chairs and pitchers of spirits—it’s minimal, but it allows the space to be used as an office, a courtroom, a hangman’s column and a seedy bar. Set dressing can make or break a play and this version was really wonderful.

We may be used to a world where twists and turns are automatic and presumed. Linear storytelling has become something of a classical approach. The end of Witness for the Prosecution was tremendous when it was first published—and truthfully, the lady sitting next to me in the public gallery let out a gasp when the reveal emerged at the end of the play. It might be nice for Agatha Christie to know, almost 100 years later, that she’s still got it.