100 Must-Read Classics in Translation

If ever there was a time to read books from different cultures and time periods, this is it. We have so much information and so many stories from around the world available to us, and yet so often we (myself included) end up reading books about ourselves, more or less. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, but why not pick up a book in translation now and then, and why not try a book from the past? Here is a list of classics in translation from around the world, written in languages other than English, that have something to teach us about our fellow human beings.

The books below were published at least 50 years ago (so nothing after 1967). The book descriptions come from publisher copy.

The Odyssey by Homer, translated by Robert Fagles (Greece, 8th century B.C.): “If the Iliad is the world’s greatest war epic, then the Odyssey is literature’s grandest evocation of everyman’s journey through life.“

Stung with Love: Poems and Fragments of Sappho by Sappho, translated by Aaron Poochigian (Greece, c. 630–570 B.C.): “Little remains today of [Sappho’s] writings … The surviving texts consist of a lamentably small and fragmented body of lyric poetry—among them poems of invocation, desire, spite, celebration, resignation and remembrance.”

Antigone by Sophocles, translated by E.H. Plumtre (Greece, 441 B.C.): “[Antigone, which is] the first Theban play written by Sophocles yet chronologically last in the cycle, is a masterpiece of classical antiquity which examines the conflict between public duty and personal loyalty.”

The Selected Poems of T’ao Ch’ien by T’ao Ch’ien, translated by David Hinton (China, early 400s): “T’ao Ch’ien, (365–427, C.E.), [is] one of the most revered poets in classical Chinese literature.”

The Kagero Diary by a woman known only as the Mother of Michitsuna, translated by Sonja Arntzen (Japan c. 974): “Japan is the only country in the world where it was primarily the works of women writers that laid the foundation for the classical literary tradition. The Kagero Diary is the first extant work of that rich and brilliant tradition.”

The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, translated by Meredith McKinney (Japan, 990s–early 1000s): “Written by the court gentlewoman Sei Shonagon, ostensibly for her own amusement, The Pillow Book offers a fascinating exploration of life among the nobility at the height of the Heian period.”

The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu, translated by Royall Tyler (Japan, early 1000s): “The Tale of Genji is a very long romance, running to fifty-four chapters and describing the court life of Heian Japan, from the tenth century into the eleventh.“

The Sarashina Diary: A Woman’s Life in Eleventh-Century Japan by Lady Sarashina, translated by Moriyuki Ito (Japan, 11th century): “A thousand years ago, a young Japanese girl embarked on a journey from the wild East Country to the capital. She began a diary that she would continue to write for the next forty years and compile later in life, bringing lasting prestige to her family.“

Selected Writings: Hildegard of Bingen by Hildegard of Bingen, translated by Mark Atherton (Germany, 12th century): “Hildegard, the ‘Sybil of the Rhine,’ was a Benedictine nun and one of the most prolific and original women writers of the Middle Ages.”

The Lais of Marie de France by Marie de France, translated by Glyn S. Burgess (France, England, late 12th century): “Marie de France (fl. late twelfth century) is the earliest known French woman poet and her lais—stories in verse based on Breton tales of chivalry and romance—are among the finest of the genre.”

The Confessions of Lady Nijo by Lady Nijo, translated by Karen Brazell (Japan, early 13th century): “In about 1307 a remarkable woman in Japan sat down to complete the story of her life. The result was an autobiographical narrative, a tale of thirty-six years (1271–1306) in the life of Lady Nijo, starting when she became the concubine of a retired emperor in Kyoto at the age of fourteen and ending, several love affairs later, with an account of her new life as a wandering Buddhist nun.”

Essays in Idleness by Yoshida Kenkō, translated by Meredith McKinney (Japan, 1330–1332): “The Buddhist priest Kenko clung to tradition, Buddhism, and the pleasures of solitude, and the themes he treats in his Essays, written sometime between 1330 and 1332, are all suffused with an unspoken acceptance of Buddhist beliefs.“

The Book of the City of Ladies by Christine de Pizan, translated by Rosalind Brown-Grant (French Italian, 1405): “The pioneering Book of the City of Ladies begins when, feeling frustrated and miserable after reading a male writer’s tirade against women, Christine de Pizan has a dreamlike vision where three virtues—Reason, Rectitude and Justice—appear to correct this view.”

The Inferno by Dante Alighieri, translated by Robert Hollander (Italy, 1472): “Guided by the poet Virgil, Dante plunges to the very depths of Hell and embarks on his arduous journey towards God.“

The Heptameron by Marguerite Navarre, translated by Paul Chilton (France, 1559): “In the early 1500s five men and five women find themselves trapped by floods and compelled to take refuge in an abbey high in the Pyrenees. When told they must wait days for a bridge to be repaired, they are inspired—by recalling Boccaccio’s Decameron—to pass the time in a cultured manner by each telling a story every day.”

The Essays: A Selection by Michel de Montaigne, translated by M.A. Screech (France, late 16th century): “To overcome a crisis of melancholy after the death of his father, Montaigne withdrew to his country estates and began to write, and in the highly original essays that resulted he discussed themes such as fathers and children, conscience and cowardice, coaches and cannibals, and, above all, himself.”

Don Quixote by Miguel Cervantes, translated by Edith Grossman (Spain, 1615): “Widely regarded as one of the funniest and most tragic books ever written, Don Quixote chronicles the adventures of the self-created knight-errant Don Quixote of La Mancha and his faithful squire, Sancho Panza, as they travel through sixteenth-century Spain.”

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz: Selected Works by Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, translated by Edith Grossman (Mexico, 17th century): “Sor Juana (1651–1695) was a fiery feminist and a woman ahead of her time. Like Simone de Beauvoir, she was very much a public intellectual. Her contemporaries called her ‘the Tenth Muse’ and ‘the Phoenix of Mexico,’ names that continue to resonate.”

Selected Letters by Madame de Sévigné, translated by Leonard Tancock (France, 17th century): “One of the world’s greatest correspondents, Madame de Sévigné (1626–96) paints an extraordinarily vivid picture of France at the time of Louis XIV, in eloquent letters written throughout her life to family and friends.”

The Princess of Cleves by Madame de La Fayette, translated by Robin Buss (France, 1678): “Poised between the fading world of chivalric romance and a new psychological realism, Madame de Lafayette’s novel of passion and self-deception marks a turning point in the history of the novel.”

The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Matsuo Basho, translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa (Japan, 1694): “In his perfectly crafted haiku poems, Basho described the natural world with great simplicity and delicacy of feeling.”

Letters of a Peruvian Woman by Françoise de Graffigny, translated by Jonathan Mallinson (France, 1747): “One of the most popular novels of the eighteenth century, the Letters of a Peruvian Woman recounts the story of Zilia, an Inca Virgin of the Sun, who is captured by the Spanish conquistadores and brutally separated from her lover, Aza.”

The Story of the Stone by Cao Xueqin, translated by David Hawkes (China, mid 18th century): “Through the changing fortunes of the Jia family, this rich, magical work sets worldly events—love affairs, sibling rivalries, political intrigues, even murder—within the context of the Buddhist understanding that earthly existence is an illusion and karma determines the shape of our lives.“

The Story of Beauty and the Beast by Madame de Villeneuve, translated by James Robinson Planche (France, 1740): “This book contains the original tale by Madame de Villeneuve, first published in 1740.”

The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, translated by David Constantine (Germany, 1774): “Goethe’s story of a sensitive young artist—an alienated youth of searching introspection and passionate intensity—captured the Romantic sensibility of the day and led to a wave of imitations.”

Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, translated by P.W.K. Stone (France, 1782): “the Vicomte de Valmont and the Marquise de Merteuil, form an unholy alliance and turn seduction into a game—a game which they must win.“

Voyage Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre, translated by Stephen Sartarelli (France, 1794): “Admired by Nietzsche and Machado de Assis, Ossian and Susan Sontag, this classic book proves that sitting on the living-room sofa can be as fascinating as crossing the Alps or paddling up the Amazon.”

Delphine by Germaine de Staël, translated by Avriel H. Goldberger (France, 1802): “Delphine … is a profound commentary on the status of women during a critical period of French political history. Delphine‘s eighteenth-century conventional form as an epistolary novel masks its unconventional questioning of accepted values and norms.”

Indiana by George Sand, translated by Sylvia Raphael (France, 1832): “[This novel] is not only a vivid romance, but also an impassioned plea for change in the inequitable French marriage laws of the time, and for a new view of women.”

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, translated by Robin Buss (France, 1844): “Thrown in prison for a crime he has not committed, Edmond Dantes is confined to the grim fortress of If. There he learns of a great hoard of treasure hidden on the Isle of Monte Cristo and becomes determined not only to escape but to unearth the treasure and use it to plot the destruction of the three men responsible for his incarceration.”

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert, translated by Margaret Mauldon (France, 1856): “When Emma Rouault marries Charles Bovary she imagines she will pass into the life of luxury and passion that she reads about in sentimental novels and women’s magazines. But Charles is a dull country doctor, and provincial life is very different from the romantic excitement for which she yearns.”

Les Miserables by Victor Hugo, translated by Julie Rose (France, 1862): “The story of how the convict Jean-Valjean struggled to escape his past and reaffirm his humanity, in a world brutalized by poverty and ignorance, became the gospel of the poor and the oppressed.”

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Russia, 1866): “A troubled young man commits the perfect crime: the murder of a vile pawnbroker whom no one will miss.”

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Russia, 1873–1877): “Anna Karenina tells of the doomed love affair between the sensuous and rebellious Anna and the dashing officer, Count Vronsky. Tragedy unfolds as Anna rejects her passionless marriage and thereby exposes herself to the hypocrisies of society.”

A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen, translated by Michael Meyer (Norway, 1879): “A Doll’s House is a masterpiece of theatrical craft which, for the first time portrayed the tragic hypocrisy of Victorian middle class marriage on stage. The play ushered in a new social era and ‘exploded like a bomb into contemporary life.'”

The Saga of Gosta Berling by Selma Lagerlof, translated by Paul Norlen (Sweden, 1891): “The eponymous hero, a country pastor whose appetite for alcohol and indiscretions ends his career, falls in with a dozen vagrant Swedish cavaliers and enters into a power struggle with the richest woman in the province.“

Selected Poems of Gabriela Mistral by Gabriela Mistral, translated by Ursula K. LeGuin (Chile, early 20th century): “The first Nobel Prize in literature to be awarded to a Latin American writer went to the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral. Famous and beloved during her lifetime all over Latin America and in Europe, Mistral has never been known in North America as she deserves to be.”

The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa, translated by Margaret Jull Costa (Portugal, early 20th century): “An ‘autobiography’ or ‘diary’ containing exquisite melancholy observations, aphorisms, and ruminations, this classic work grapples with all the eternal questions.”

The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova by Anna Akhmatova, translated by Judith Hemschemeyer (Russia, early 20th century): “From the artistic passion of the St Petersburg poets and bohemians, to the collective suffering of a nation, Anna Akhmatova spoke to, and for, the soul of her people.”

The Cherry Orchard by Anton Chekhov, translated by Michael Heim (Russia, 1904): “[The Cherry Orchard] is one of the most critically admired and performed plays in the Western world, a high comedy whose principal theme, the passing of the old semifeudal order, is symbolized in the sale of the cherry orchard owned by Madame Ranevsky.”

I am a Cat by Soseki Natsume, translated by Katsue Shibata and Motonari Kai (Japan, 1905): “The novel-essay I Am a Cat by Soseki Natsume is considered a milestone in contemporary Japanese literature. In it, we have a glimpse of Japanese life at the early part of the twentieth century as seen by a cat.”

Jakob von Gunten by Robert Walser, translated by Christopher Middleton (Switzerland, 1909): “[This novel] tells the story of a seventeen-year-old runaway from an old family who enrolls in a school for servants.“

Swann’s Way: In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust, translated by Lydia Davis (France, 1913): “Swann’s Way is one of the preeminent novels of childhood: a sensitive boy’s impressions of his family and neighbors, all brought dazzlingly back to life years later by the taste of a madeleine.”

The Wild Geese by Ogai Mori, translated by Sanford Goldstein (Japan, 1913): “In The Wild Geese, prominent Japanese novelist Ogai Mori offers a poignant story of unfulfilled love, set against the background of the dizzying social change accompanying the fall of the Meiji regime.”

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka, translated by Michael Hoffman (Austria-Hungary, 1915): “The Metamorphosis is the story of a young man who, transformed overnight into a giant beetle-like insect, becomes an object of disgrace to his family, an outsider in his own home, a quintessentially alienated man.“

Rashomon and Other Stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, translated by Takashi Kojima (Japan, 1915): “This fascinating collection gave birth to a new paradigm when Akira Kurosawa made famous Akutagawa’s disturbing tale of seven people recounting the same incident from shockingly different perspectives.”

The Home and the World by Rabindranath Tagore, translated by Surendranath Tagore (India, 1916): “Set on a Bengali noble’s estate in 1908, this is both a love story and a novel of political awakening. The central character, Bimala, is torn between the duties owed to her husband, Nikhil, and the demands made on her by the radical leader, Sandip.”

Chéri and the Last of Chéri by Colette, translated by Roger Senhouse (France, 1920): “Chéri, together with The Last of Chéri, is a classic story of a love affair between a very young man and a charming older woman.”

Kristin Lavransdatter by Sigrid Undset, translated by Tiina Nunnally (Denmark, 1920–1922): “In her great historical epic Kristin Lavransdatter, set in fourteenth-century Norway, Nobel laureate Sigrid Undset tells the life story of one passionate and headstrong woman.“

Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse, translated by Joachim Neugroschel (Germany, 1922): “Set in India, Siddhartha is the story of a young Brahmin’s search for ultimate reality after meeting with the Buddha.”

Diary of a Madman by Lu Xun, translated by William A. Lyell (China, 1920s–1930s): “This collection of short stories by Lu Xun includes the celebrated short story, ‘A Madman’s Diary’ … is considered to be one of the first and most influential modern works written in vernacular Chinese.”

The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, translated by John E. Woods (Germany, 1924): “In this dizzyingly rich novel of ideas, Mann uses a sanatorium in the Swiss Alps—a community devoted exclusively to sickness—as a microcosm for Europe, which in the years before 1914 was already exhibiting the first symptoms of its own terminal irrationality.”

Chaka by Thomas Mofolo, translated by Daniel Kunene (Lesotho, 1925): “The author manipulates events leading to Chaka’s status of great Zulu warrior, conqueror, and king to emphasize classic tragedy’s psychological themes of ambition and power, cruelty, and ultimate ruin.”

Miss Sophie’s Diary and Other Stories by Ding Ling, translated by W.J.F. Jenner (China, 1928): “Miss Sophie’s Diary, by one of China’s best-known writers, created a sensation when first published in 1928 for the frank portrayal of a young woman’s ideals and emotions in conflict.”

All’s Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, translated by Arthur Wesley Wheen (Germany, 1929): “This is the testament of Paul Bäumer, who enlists with his classmates in the German army during World War I. They become soldiers with youthful enthusiasm. But the world of duty, culture, and progress they had been taught breaks in pieces under the first bombardment in the trenches.”

Grand Hotel by Vicki Baum, translated by Basil Creighton (Austria, 1929): “A grand hotel in the center of 1920s Berlin serves as a microcosm of the modern world in Vicki Baum’s celebrated novel, a Weimar-era best seller that retains all its verve and luster today.”

Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Charlie Louth (Germany, 1929): “Written when Rainer Maria Rilke was himself still a young man with most of his greatest work before him, [these letters] are addressed to a student who had sent Rilke some of his work, asking for advice about becoming a writer.”

The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz, translated by Celina Wieniewska (Poland, 1934): “The Street of Crocodiles in the Polish city of Drogobych is a street of memories and dreams where recollections of Bruno Schulz’s uncommon boyhood and of the eerie side of his merchant family’s life are evoked in a startling blend of the real and the fantastic.”

Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb, translated by Len Rix (Hungary, 1937): “The trouble begins in Venice, the first stop on Erzsi and Mihály’s honeymoon tour of Italy. Here Erzsi discovers that her new husband prefers wandering back alleys on his own to her company.”

A Riot of Goldfish by Kanoko Okamoto, translated by J. Keith Vincent (Japan, 1937): “In early 20th-century Japan, the son of lower-class goldfish sellers falls in love with the beautiful daughter of his rich patron. After he is sent away to study the science of goldfish breeding … he vows to devote his life to producing one ideal, perfect goldfish specimen to reflect his loved-one’s beauty.”

Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata, translated by Edward Seidensticker (Japan, 1937): “Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country is widely considered to be the writer’s masterpiece: a powerful tale of wasted love set amid the desolate beauty of western Japan.”

Child of All Nations by Irmgard Keun, translated by Michael Hofmann (Germany, 1938): “Kully knows some things you don’t learn at school … But there are also things she doesn’t understand, like why there might be a war in Europe—just that there are men named Hitler, Mussolini and Chamberlain involved.”

Beware of Pity by Stefan Zweig, translated by Phyllis Blewitt and Trevor Blewitt (Austria-Hungary, 1939): “The great Austrian writer Stefan Zweig was a master anatomist of the deceitful heart, and Beware of Pity, the only novel he published during his lifetime, uncovers the seed of selfishness within even the finest of feelings.“

The Stranger by Albert Camus, translated by Matthew Ward (France, 1942): “Through the story of an ordinary man unwittingly drawn into a senseless murder on an Algerian beach, Camus explored what he termed ‘the nakedness of man faced with the absurd.'”

Iceland’s Bell by Halldor Laxness, translated by Philip Roughton (Iceland, 1943): “At the close of the 17th century, Iceland is an oppressed Danish colony, suffering under extreme poverty, famine, and plague. A farmer and accused cord-thief named Jon Hreggvidsson makes a bawdy joke about the Danish king and soon after finds himself a fugitive charged with the murder of the king’s hangman.”

Love in a Fallen City by Eileen Chang, translated by Karen S. Kingsbury (China, 1943): “Written when Chang was still in her twenties, these extraordinary stories combine an unsettled, probing, utterly contemporary sensibility, keenly alert to sexual politics and psychological ambiguity, with an intense lyricism that echoes the classics of Chinese literature.“

The Makioka Sisters by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, translated by Edward G. Seidensticker (Japan, 1943–1948): “Junichirō Tanizaki’s magisterial evocation of a proud Osaka family in decline during the years immediately before World War II is arguably the greatest Japanese novel of the twentieth century and a classic of international literature.”

Nada by Carmen Laforet, translated by Edith Grossman (Spain, 1944): “A modern Spanish classic … The novel conveys beautifully the spirit of war-torn, brutalized Barcelona.”

No Exit by Jean-Paul Sartre, translated by Stuart Gilbert (France, 1944): “The play is a depiction of the afterlife in which three deceased characters are punished by being locked into a room together for eternity.“

Transit by Anna Seghers, translated by Margot Bettauer Dembo (Germany, 1944): “Anna Seghers’s Transit is an existential, political, literary thriller that explores the agonies of boredom, the vitality of storytelling, and the plight of the exile with extraordinary compassion and insight.”

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank, translated by B.M. Mooyaart (Netherlands, 1947): “In 1942, with the Nazis occupying Holland, a thirteen-year-old Jewish girl and her family fled their home in Amsterdam and went into hiding. For the next two years, until their whereabouts were betrayed to the Gestapo, the Franks and another family lived cloistered in the ‘Secret Annexe’ of an old office building.”

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir, translated by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (France, 1949): “Simone de Beauvoir’s essential masterwork is a powerful analysis of the Western notion of ‘woman,’ and a revolutionary exploration of inequality and otherness.”

Thus Were Their Faces by Silvina Ocampo, translated by Daniel Balderston (Argentina, mid 20th century): “Here are tales of doubles and impostors, angels and demons, a marble statue of a winged horse that speaks, a beautiful seer who writes the autobiography of her own death, a lapdog who records the dreams of an old woman, a suicidal romance, and much else that is incredible, mad, sublime, and delicious.”

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda, translated by Ilan Stavans (Chile, mid-20th century): “This selection of Neruda’s poetry, the most comprehensive single volume available in English, presents nearly six hundred poems, scores of them in new and sometimes multiple translations, and many accompanied by the Spanish original.”

The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector, translated by Katrina Dodson (Brazil, 1950s–1970s): “From one of the greatest modern writers, these stories, gathered from the nine collections published during her lifetime, follow an unbroken time line of success as a writer, from her adolescence to her death bed.“

Pinjar: The Skeleton and Other Stories by Amrita Pritam, translated by Khushwant Singh (India, 1950): “An emotional story of a girl—once kidnapped, even her father refused to accept her. She struggles to return such another girl and succeeds.”

Waiting for God by Simone Weil, translated by Emma Craufurd (France, 1950): “Emerging from the thought-provoking discussions and correspondence Simone Weil had with the Reverend Father Perrin, this classic collection of essays contains the renowned philosopher and social activist’s most profound meditations on the relationship of human life to the realm of the transcendent.”

Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar, translated by Grace Frick (France, 1951): “In [Memoirs of Hadrian], Marguerite Yourcenar reimagines the Emperor Hadrian’s arduous boyhood, his triumphs and reversals, and finally, as emperor, his gradual reordering of a war-torn world.”

Bonjour Tristesse by Francois Sagan, translated by Irene Ash (France, 1954): “Endearing, self-absorbed, seventeen-year-old Cécile is the very essence of untroubled amorality. Freed from the stifling constraints of boarding school, she joins her father…for a carefree, two-month summer vacation in a beautiful villa outside of Paris with his latest mistress, Elsa.”

The Ten Thousand Things by Maria Dermoût, translated by Hans Koning (Indonesia/Netherlands, 1955): “[This novel] is the story of Felicia, who returns with her baby son from Holland to the Spice Islands of Indonesia, to the house and garden that were her birthplace, over which her powerful grandmother still presides.”

Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz, translated by William M. Hutchins and Olive E. Kenny (Egypt, 1956): “A national best-seller in both hardcover and paperback, it introduces the engrossing saga of a Muslim family in Cairo during Egypt’s occupation by British forces in the early 1900s.“

Arturo’s Island by Elsa Morante, translated by Isabel Quigley (Italy, 1957): “Arturo’s mother is dead; his father away. Black-clad women care for him, give him the freedom to come and go as he likes. Then the father returns with a new wife, Nunziata, a girl barely older than Arturo.”

The Waiting Years by Fumiko Enchi, translated by John Bester (Japan, 1957): “In a series of colorful, unforgettable scenes, Enchi brilliantly handles the human interplay within the ill-fated Shirakawa family.“

Memoirs of a Woman Doctor by Nawal El Saadawi, translated by Catherine Cobham (Egypt, 1958): “Rebelling against the constraints of family and society, a young Egyptian woman decides to study medicine, becoming the only woman in a class of men.”

The Planetarium by Nathalie Sarraute, translated by Maria Jolas (France, 1959): “A young writer has his heart set on his aunt’s large apartment. With this seemingly simple conceit, the characters of The Planetarium are set in orbit and a galaxy of argument, resentment, and bitterness erupts.”

The Open Door by Latifa al-Zayyat, translated by Marilyn Booth (Egypt, 1960): “Published in 1960, [this book] was very bold for its time in exploring a middle-class Egyptian girl’s coming of sexual and political age, in the context of the Egyptian nationalist movement preceding the 1952 revolution.“

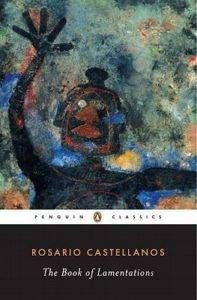

The Book of Lamentations by Rosario Castellanos, translated by Ester Allen (Mexico, 1962): “Set in the highlands of the Mexican state of Chiapas, The Book of Lamentations tells of a fictionalized Mayan uprising that resembles many of the rebellions that have taken place since the indigenous people of the area were first conquered by European invaders five hundred years ago.”

The Death of Artemio Cruz by Carlos Fuentes, translated by Alfred MacAdam (Mexico, 1962): “As the novel opens, Artemio Cruz, the all-powerful newspaper magnate and land baron, lies confined to his bed and, in dreamlike flashes, recalls the pivotal episodes of his life. Carlos Fuentes manipulates the ensuing kaleidoscope of images with dazzling inventiveness, layering memory upon memory.”

Labyrinths by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby (Argentina, 1962): “Labyrinths is a representative selection of Borges’ writing, some forty pieces drawn from various of his books published over the years.“

The Little Virtues by Natalia Ginzburg, translated by Dick David (Italy, 1962): “Ginzburg brings to her reflections the wisdom of a survivor and the spare, wry, and poetically resonant style her readers have come to recognize.”

Hopscotch: A Novel by Julio Cortazar, translated by Gregory Rabassa (Argentina, 1963): “Horacio Oliveira is an Argentinian writer who lives in Paris with his mistress, La Maga, surrounded by a loose-knit circle of bohemian friends who call themselves ‘the Club.’ A child’s death and La Maga’s disappearance put an end to his life of empty pleasures and intellectual acrobatics.”

Iza’s Ballad by Magda Szabo, translated by George Szirtes (Hungary, 1963): “Iza’s Ballad is a striking story of the relationship between two women, in this case a mother and a daughter.”

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea by Yukio Mishima, translated by John Nathan (Japan, 1963): “Yukio Mishima’s The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea explores the vicious nature of youth that is sometimes mistaken for innocence.”

They Divided the Sky by Christa Wolf, translated by Luise von Flotow (Germany, 1963): “They Divided the Sky tells the story of a young couple, living in the new, socialist, East Germany, whose relationship is tested to the extreme not only because of the political positions they gradually develop but, very concretely, by the Berlin Wall, which went up on August 13, 1961.”

A Personal Matter by Kenzaburō Ōe, translated by John Nathan (Japan, 1964): ” A Personal Matter is the story of Bird, a frustrated intellectual in a failing marriage whose Utopian dream is shattered when his wife gives birth to a brain-damaged child.”

The Ravishing of Lol Stein by Marguerite Duras, translated by Richard Seaver (France, 1964): “Lol Stein is a beautiful young woman, securely married, settled in a comfortable life—and a voyeur. Returning with her husband and children to the town where, years before, her fiancé had abandoned her for another woman, she is drawn inexorably to recreate that long-past tragedy.”

Closely Watched Trains by Bohumil Hrabal, translated by Edith Pargeter (Czech, 1965): “Hrabal’s postwar classic about a young man’s coming of age in German-occupied Czechoslovakia is among his most popular works. Milos Hrma is a timid railroad apprentice who insulates himself with fantasy against a reality filled with cruelty and grief.”

The Doctor’s Wife by Sawako Ariyoshi, translated by Wakako Hironaka (Japan, 1966): “Thus, this novel is really two stories: on the one hand, the successful medical career of Hanaoka Seishu, the first doctor in the world to perform surgery for breast cancer under a general anesthetic; on the other hand, the lives of his wife and his mother.”

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Russia, 1966): “Mikhail Bulgakov’s fantastical, funny, and devastating satire of Soviet life combines two distinct yet interwoven parts, one set in contemporary Moscow, the other in ancient Jerusalem, each brimming with historical, imaginary, frightful, and wonderful characters.”

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, translated by Gregory Rabassa (Colombia, 1967): “One Hundred Years of Solitude tells the story of the rise and fall, birth and death of the mythical town of Macondo through the history of the Buendia family.”

What are your favorite classics in translation? Any that I missed?