StarTalk: An Interview with Neil deGrasse Tyson

Swapna sits down with Dr. Neil deGrasse Tyson to discuss StarTalk, Twitter, being starstruck, and Hogwarts houses.

Swapna Krishna: StarTalk is at the intersection of pop culture and science. Why did you start it?

Dr. Neil deGrasse Tyson: StarTalk began as a radio show (and it still is one—we produce 50 shows a year), and what has happened in the past two years is that it’s also jumped species. National Geographic took enough interest in it to levitate 20 of those 50 shows for the television universe, and so now there are 20 shows a year that air on the National Geographic channel.

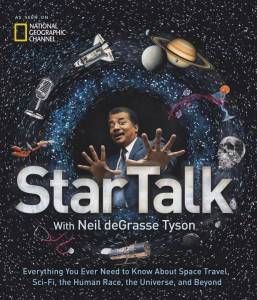

National Geographic Books took an interest in it, and so [Tuesday] is the StarTalk book. So the origins go back to the radio days where we began the program on a grant from the National Science Foundation (from the education division), and it has fascinating academic roots to it. It was a vibrant attempt to try to spread the love of science to whoever will listen or pay attention.

National Geographic Books took an interest in it, and so [Tuesday] is the StarTalk book. So the origins go back to the radio days where we began the program on a grant from the National Science Foundation (from the education division), and it has fascinating academic roots to it. It was a vibrant attempt to try to spread the love of science to whoever will listen or pay attention.

What we proposed was we know there are programs you might tune into if you already know you like science. There’s documentaries on television, there’s Science Fridays, a popular NPR program on the radio, but we thought, “How about the people who don’t know they like science?” Or even better yet, the people who are sure they don’t like science. Is there a way to reach them? StarTalk was formulated to gain access to people who wouldn’t otherwise be thinking of science because we inverted the model—I’m the host. I’m the scientist. The guests that I interview are hardly ever scientists. They’re people hewn of pop culture. When you do that, they have a following, and we have a following, and you follow your person wherever they go, and now their followers will hear them having a conversation about science and all the way in which science has touched their lives. What it comes down to is, and the way I like to think of it is, pop culture is the scaffold we all carry around with us. It requires no training, no special lessons. When you bring it into StarTalk, we clad that scaffold with scientific insights and knowledge and wisdom, and then you end up realizing how prevalent science is in our lives and in our culture. And I like to think that’s one way we can spread people’s awareness of science, and in the 21st century, hopefully we can have a scientifically literate electorate. So that’s the whole backstory right there.

SK: Going off that, on StarTalk, on Twitter, in a lot of your projects, making science accessible and interesting to a non-scientific audience has been such a passion of yours. Has that always been a passion of yours, and why is it so important?

NdT: All of this looks the same on the outside, but on the inside it’s a little different. My Twitter following, which every morning I wake up and I say “WHAT?” Should I remind these people that I’m an astrophysicist? What accounts for this following? The last time I checked, it was rising through 5.6 million. So clearly it’s more than just the geeks out there who are tuning in to these various outlets. So Twitter is not some mission statement that I’m on. I realized when I started doing Twitter in a meaningful way—in the early days, it was like “Oh, I’m crossing the park now, getting a hamburger”—I said, I’m an educator and I’m a scientist, surely there’s a lot of stuff I can put in this powerful medium.

I realized that I have thoughts every day that are themselves tweets. Just simple little thoughts—I’ll give you an example. I was sitting there at a red light in my car, and I said, “We stop for red and we go with green,” and that’s probably because blood is red and red is dangerous. But suppose our blood used copper instead of iron for hemoglobin, as do crustaceans, as does Spock on Star Trek. Then our blood would be green. So if we had green blood, what color would a spotlight be?

And I said, if I can pare that down to 140 characters, that’s a tweet! So it’s just a simple thought, and when I started doing that, I think people sharing this lens that I carry around with me. I take it for granted that I have this educator/scientist lens, and you’re sharing with me what the world looks like through my lens.

But I’m having these thoughts anyway. I’m not starting my day wondering, “What thoughts can I put out there to the public?” So it’s not a mission statement so much as it is sharing the life that I’ve been given.

SK: So then, how do you compare what you do on Twitter to, for example, hosting Cosmos or StarTalk, besides the fact that Twitter is 140 characters and these are much longer?

NdT: That’s an excellent and perceptive question because there are certain things they have in common, and I didn’t realize it until I paused and reflected back on what I was doing. What they have in common is—Cosmos a little less so, because that was much more collaborative, but for the rest of these activities, what I found myself doing was connecting science to everyday life. The things you’re already familiar with. And I found that had the highest resonance, because that’s how I think about it. Some of it requires that I, myself, carry some fluency in pop culture so that I can think of these on-the-spot connections. I’ve always been interested in pop culture. Some of my colleagues think of pop culture as beneath them, or there’s the ivory tower and then there’s everybody else, and I never could buy into that wall that’s been put up by so many people over the decades and even the centuries.

So I see myself in pop culture. I listen to pop music, I do pop things, and I’m also a scientist, so why don’t I just share these observations with people? So I do that on Twitter. StarTalk is all about the intersection of pop culture and science, with a humorous dimension added more for levity when the topic deepens, which is why my cohost is always a professional stand-up comedian. All of those activities have that in common. And in that way, the science is not some lesson plan you have to sit down and get ready for because it’s plugging into something you already care about. And in that way, there’s much less resistance to learning, when it’s conceived and presented in that manner.

SK: As you mentioned, StarTalk has quite the roster of celebrity guests. Season 3 features, among others, Buzz Aldrin, Andy Weir, Jay Leno, and Whoopi Goldberg. Have you ever been starstruck by any of your celebrity guests?

NdT: [Laughs] It’s not that I’m starstruck, what I am is…it’s different than…well, maybe it is starstruck! If I get someone who is hugely, singularly achieved, then being in the presence who has achieved such high innovative levels or popularity levels or maybe they invented something—I interviewed Elon Musk, for example, in a different season, or we interviewed Biz Stone, one of the cofounders of Twitter. Just to get into his head, to learn what was going on—this, for me, is an intriguing and enlightening exercise of discovery—just for me. And it’s not that they’re famous—some of them, you might not have even heard of—it’s just that I like knowing how people think. I like seeing how people have succeeded when others would have presumed they would have failed, and others just go along with whatever everyone else does.

So the people we interview have achieved in that way. And that, I find equally satisfying to speak to them and equally enlightening. For others, I’d say Bill Clinton, but I actually have history with Bill Clinton. I was invited to the White House back in the year 2000 for the new millennium. There were two speakers, one who was an expert on the oceans, and I was brought in as an expert on the universe, and we just gave a talk. And so there’s Bill and Hillary just sitting there in the audience—well, they actually sitting in a different place, but they were in MY audience! So there was a little bit of history there.

But I had never met Jimmy Carter before, that was last year we had him on—he was the first person I voted for, I had just turned 18 the year he ran for president, so that was a special meeting for me, to see how much of his life has been devoted to humanitarian causes. I mean, there’s a person who has had a very full life just trying to make the world a better place.

At the end of the day, the diversity of people’s backgrounds is not a common denominator. The common denominator is every one of them has been touched by science, by engineering, by technology in some way, and for others among them, they actually have some geek underbelly [laughs] the soft geek underbelly that we reveal on the show that might not have been revealed at all. So I enjoyed discovering that with the viewer when that happens.

SK: We are a book community, so I wanted to ask a couple of book-related questions.

Do you know your Hogwarts house?

NdT: [Laughs. Very hard.]

SK: Inquiring minds want to know!

NdT: My kids have asked me that, and no, I don’t know. There’s a quiz, and I even took the quiz two years ago, and I do not remember what house they assigned me to. So I fail at this, I’m sorry.

SK: That’s okay!

[Note: We think Dr. Tyson is a Ravenclaw]

What are you reading right now? Or what would you recommend?

NdT: Oh, I don’t ever tell people what to do! Even if it seems and feels that way sometimes, I don’t think I should tell a person how to spend their money. I try not to tell people what to read.

But at the moment, I’m reading al-Ghazali, a thousand-year-old Islamic philosopher, and he has a book called Letter to a Disciple. He wrote it later in his life, so it’s very summative of his philosophy. I’m just reading about people were thinking a thousand years ago in Baghdad. There was a transition going on—Baghdad being the intellectual capital of the world where major advances were made in agriculture and mathematics and engineering and medicine and astronomy, and then that all sort of collapsed. And I was trying to understand how such a intellectually fertile environment can lose its compass bearing. Because I think about the creative centers today—countries, or even regions. Will Silicon Valley always be as innovative? Will the United States be innovative, or will we become complacent?

I tend to read nonfiction. There are a lot of books in rotation, and the al-Ghazali is the one book during this one phone call that I happen to be reading. It’s a very short book, actually, 30 pages or so. With translations and notes, it’s about 50 pages. But the brief takeaway is that I try to read what I don’t yet know fully, to enhance the perspectives that I bring to my life and my evaluation of all that goes on in this world. So often you ask what’s on your bookshelf, and people list all these books and go, “Oh! I guess you like that topic” or “I guess you really are into that!” and for me, it’s kind of the opposite. There are books on my shelf that I’m not into. They are things I don’t know anything about yet. It’s going to lead me off into a new place. The books don’t represent an interest; they represent a source of my ignorance.

SK: For my last question, I’m going to be selfish and ask a space nerd question (because I’m a huge space nerd). OSIRIS-REx, an unmanned NASA spacecraft heading to the asteroid Bennu, launched Thursday. Do you think the future of science in space is with unmanned spacecraft, humans in space, or some combination of the two?

NdT: People mix together two pathways that I think they shouldn’t be. One of them is it’s fun to explore space and make discoveries. So this [OSIRIS-REx] is a primarily scientific adventure, and then there are adventure adventures. The people that first climbed Mt. Everest weren’t scientists, right, they were adventurers. If you’re an adventurer, you want to go yourself. It’s different than a scientist, who is simply wanting to learn.

Essentially every scientist, when posed with the question, “If you want to get science knowledge from Mars, do you want to send a geologist or do you want to send a robot?” Well, the real answer is, you can send 100 robots for the price of sending one geologist, so let’s send 100 robots to 100 different locations, and then we would all benefit. So that’s the answer you would get. And I agree with that answer.

But there’s another side of this, which is space as a tourist destination or as a business enterprise, and the military is surely thinking about space as the new high ground. There are all these other reasons that men might want to go into space. I’ve said multiple times that the world’s first trillionaire is going to be the person who exploits the resources of asteroids, the natural resources that are rare on earth and common on selected asteroids. So there are many different reasons you might want to go into space. You might want to spend your honeymoon on the far side of the moon.

To view space as, “Well, let’s go to Mars now,” or “Let’s do this now,” maybe we should rethink of space as our backyard and have a suite of launch vehicles that can enable any ambition a person has regarding space. It’s the same way you can go to buy a car: I want to go offroading, I’ll buy this model. I’m a city driver, that’s this model. I want to use less fuel, well, that’s this model. They’re not selling you one car, you have options. So when I think of space, I think of having options. Of course, we’re not there yet, but I’d love to think that in 100 years’ time, that will be the case. The Earth is just one place of many that we could hang our hats.

StarTalk: Everything You Ever Need to Know About Space Travel, Sci-Fi, the Human Race, the Universe, and Beyond by Neil deGrasse Tyson, Jeffrey Simons, and Charles Liu releases today (September 13, 2016) from National Geographic Books. Thank you to Dr. Tyson for giving us your time.