A Brief (and Admittedly Incomplete) History of Cookbooks

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

On Saturday mornings in my house, my wife and I sit on the sofa with cups of coffee and talk about food. What we want to eat, what we have leftover, what we should plan for the week ahead. And once we establish what we want, we turn to our cookbooks, as generations of home cooks have done before. We’re part of a lineage, sure, but where did it start? What is the history of cookbooks? What were the firsts? Who were they for? Who wrote them, and what did they say about the people who cooked?

We have a variety on our shelf—old standards like Better Homes and Gardens, with its red and white checked pattern, Joy of Cooking, a classic—and newer additions. Deb Perelman, for example, is my kitchen oracle, who has never steered me wrong and who never shall. Chrissy Teigen’s Cravings is there to lend humor and variety. But a shelf full of cookbooks hasn’t always been the norm. I took a dive into the world of cookbook writing and publishing to compile this brief (and admittedly incomplete) history of cookbooks.

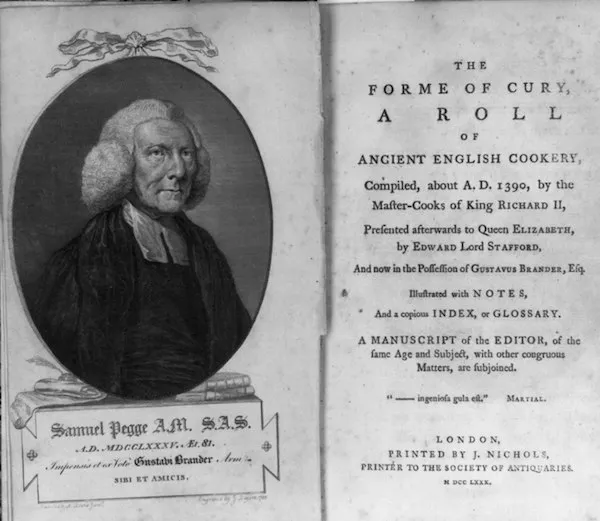

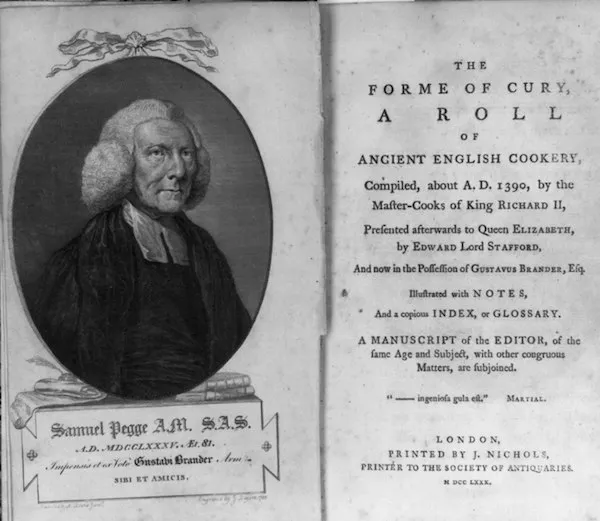

The first cookbook in English was Forme of Cury, which was written by the chefs of King Richard II in 1390 (Jurafsky, 2014). Dan Jurafsky takes us through a linguistic study of different food words that appear in that book, their translations or movements in and through different languages (English, Latin, French), and how those words eventually become the words we use today, like soup or supper.

An emphasis here is interesting: clay tablets made up the world’s first cookbooks, and the stew contained therein was a favorite of kings for hundreds of years. The first English cookbook was written for King Richard II. As time went on, however, cookbooks switched from a record of the nobility to instruction for the common man.

The first cookbook in English was Forme of Cury, which was written by the chefs of King Richard II in 1390 (Jurafsky, 2014). Dan Jurafsky takes us through a linguistic study of different food words that appear in that book, their translations or movements in and through different languages (English, Latin, French), and how those words eventually become the words we use today, like soup or supper.

An emphasis here is interesting: clay tablets made up the world’s first cookbooks, and the stew contained therein was a favorite of kings for hundreds of years. The first English cookbook was written for King Richard II. As time went on, however, cookbooks switched from a record of the nobility to instruction for the common man.

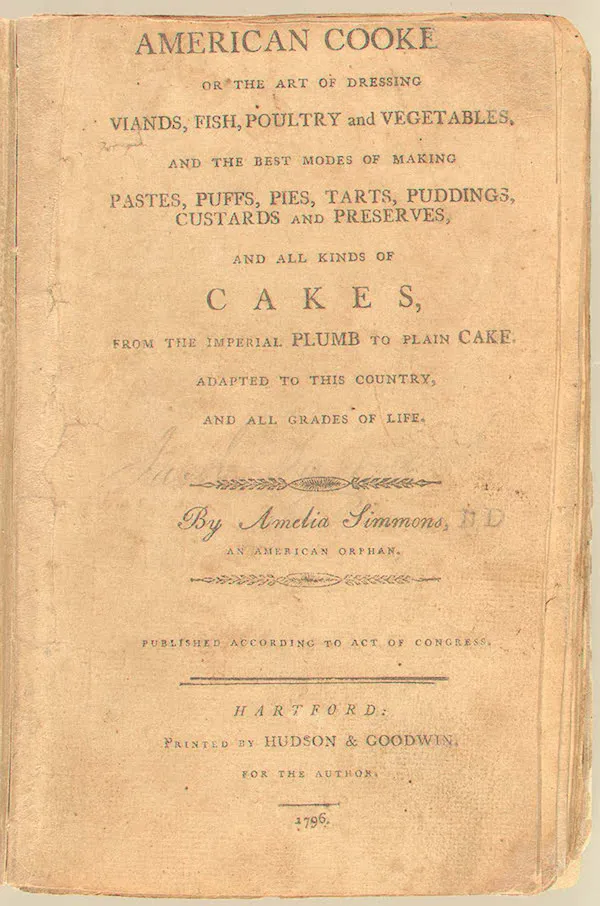

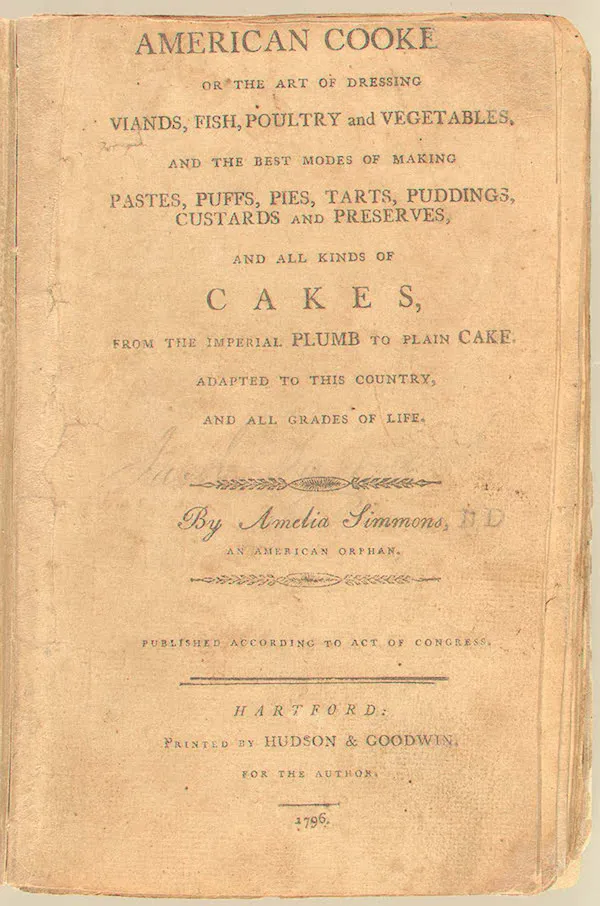

Which brings us to the first cookbook written by an American, American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons in 1796. Now, the inscription here says that this cookbook has been “adapted to this country and all grades of life.” But let’s be clear: in 1796, all grades of life were not purchasing cookbooks. However, it continued to be printed and reprinted for more than 30 years before it fell off the radar. It has been reclaimed and studied now as a foundation text in American history (SmithsonianMag.com, 2018).

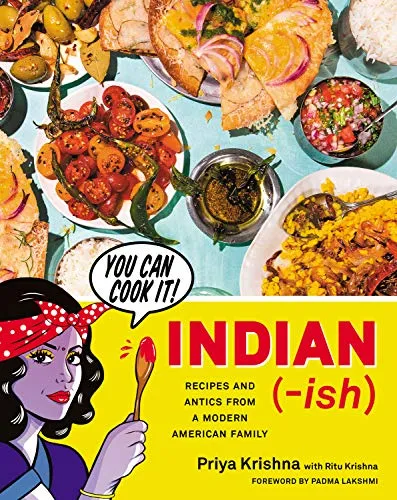

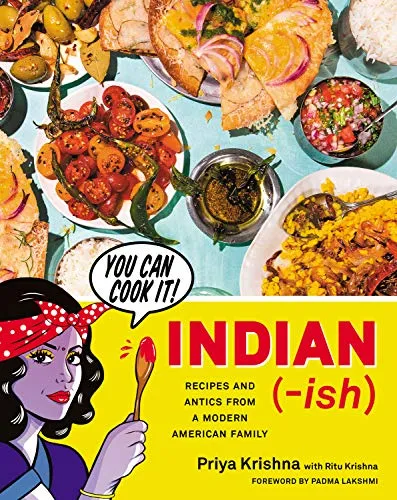

While this early history is great, it’s important that we jump forward a bit. You may have noticed a very distinct difference in the format and appearance of say, American Cookery, and one of this year’s top cookbooks, Indian-ish.

Which brings us to the first cookbook written by an American, American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons in 1796. Now, the inscription here says that this cookbook has been “adapted to this country and all grades of life.” But let’s be clear: in 1796, all grades of life were not purchasing cookbooks. However, it continued to be printed and reprinted for more than 30 years before it fell off the radar. It has been reclaimed and studied now as a foundation text in American history (SmithsonianMag.com, 2018).

While this early history is great, it’s important that we jump forward a bit. You may have noticed a very distinct difference in the format and appearance of say, American Cookery, and one of this year’s top cookbooks, Indian-ish.

It’s obvious that with the progression forward in publishing, printing, mass production, and diversity, we are now in a very different culinary publishing landscape. So let’s move on from the early, foundational texts, into the cookbooks that formed our modern understanding, and expectation, of cookbooks.

It’s obvious that with the progression forward in publishing, printing, mass production, and diversity, we are now in a very different culinary publishing landscape. So let’s move on from the early, foundational texts, into the cookbooks that formed our modern understanding, and expectation, of cookbooks.

The first cookbook authored by an African American was A Domestic Cookbook: Containing a Careful Selection of Receipts for the Kitchen by Mrs. Malinda Russell, published in 1866. It’s interesting that American Cookery specifies the author is “an orphan,” where Mrs. Malinda Russell is specifically characterized as “an experienced cook.” She came from a family of freed slaves, and her experience as a cook no doubt comes from that family history. She worked as a cook, later kept a boarding house and a pastry shop, and then left the South for Michigan, where she learned even more in her cooking. Her cookbook focuses primarily on pastries.

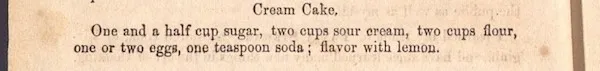

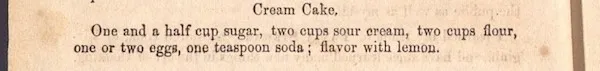

The format of her recipes follows the common format of many 19th century recipes in that the cookbook author assumes a certain amount of competence on the part of the reader (McLoone, 2016). Take a look at this recipe for Cream Cake from Russell’s book:

The first cookbook authored by an African American was A Domestic Cookbook: Containing a Careful Selection of Receipts for the Kitchen by Mrs. Malinda Russell, published in 1866. It’s interesting that American Cookery specifies the author is “an orphan,” where Mrs. Malinda Russell is specifically characterized as “an experienced cook.” She came from a family of freed slaves, and her experience as a cook no doubt comes from that family history. She worked as a cook, later kept a boarding house and a pastry shop, and then left the South for Michigan, where she learned even more in her cooking. Her cookbook focuses primarily on pastries.

The format of her recipes follows the common format of many 19th century recipes in that the cookbook author assumes a certain amount of competence on the part of the reader (McLoone, 2016). Take a look at this recipe for Cream Cake from Russell’s book:

The title is followed by the ingredients in the order that they should be followed. Here, however, we also see that the author leaves certain matters to the cook: the number of eggs, the amount of lemon flavor. This was common in cookbooks of the time, but it lays the groundwork for the recipe format to come just 30 years later.

Moving into the 20th century, access to education and the written word; ability to mass produce books; and a shift in the balance of who cooks, for whom, and with what agency all affected how Americans ate. Advances in technology also played a huge part in our culinary history. Consider that at one point, we didn’t have standard measuring spoons or cups. Stoves were lit by fire, which is hard to regulate, followed (thankfully) by gas and then electric. All of which helped to standardize the logistics of cooking, but we needed a cookbook that accomplished the same thing.

The title is followed by the ingredients in the order that they should be followed. Here, however, we also see that the author leaves certain matters to the cook: the number of eggs, the amount of lemon flavor. This was common in cookbooks of the time, but it lays the groundwork for the recipe format to come just 30 years later.

Moving into the 20th century, access to education and the written word; ability to mass produce books; and a shift in the balance of who cooks, for whom, and with what agency all affected how Americans ate. Advances in technology also played a huge part in our culinary history. Consider that at one point, we didn’t have standard measuring spoons or cups. Stoves were lit by fire, which is hard to regulate, followed (thankfully) by gas and then electric. All of which helped to standardize the logistics of cooking, but we needed a cookbook that accomplished the same thing.

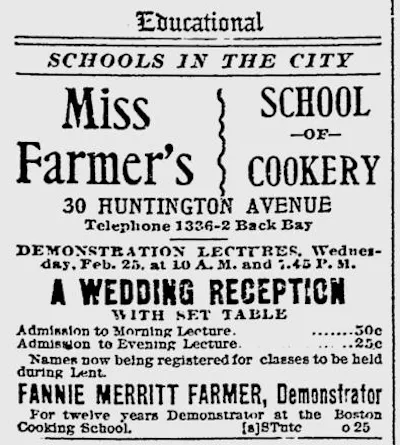

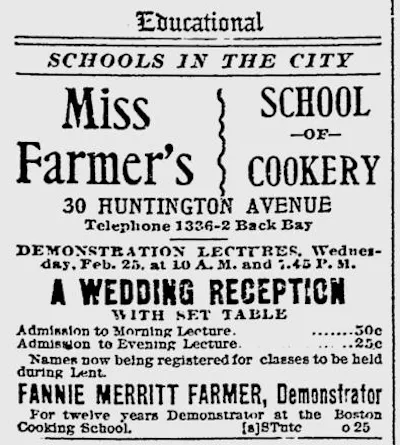

Fannie Mae Farmer’s The Boston Cooking School Cookbook was published in 1896 and exhibits the modern recipe format that we know today. Farmer’s goal was to create recipes that could be consistently replicated in any home kitchen. She was well-known also for her radio show about cooking, and she ran The Boston Cooking School. Her cookbook was the first of many of its kind, and its format is one we have built on.

Fannie Mae Farmer’s The Boston Cooking School Cookbook was published in 1896 and exhibits the modern recipe format that we know today. Farmer’s goal was to create recipes that could be consistently replicated in any home kitchen. She was well-known also for her radio show about cooking, and she ran The Boston Cooking School. Her cookbook was the first of many of its kind, and its format is one we have built on.

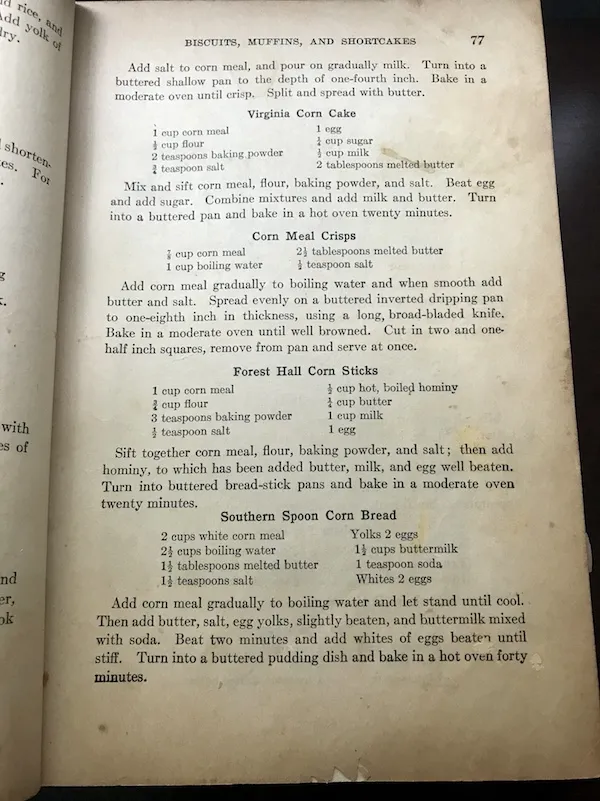

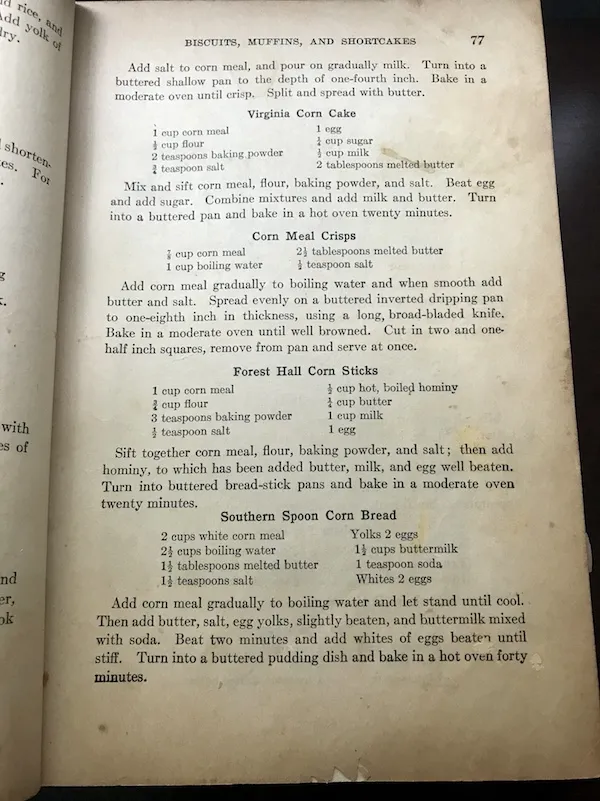

The classic format we see here is title, a list of ingredients, and the steps to follow. You can see, however, that even Ms. Farmer assumes a certain level of competence in her reader. The recipe for Forest Hall Corn Sticks asks you to add hominy, to which you have already added butter, milk, and egg. Modern recipes would likely tell you to add the butter, milk, and egg to the hominy, then set aside and continue until it’s needed again.

I’m going to skip ahead here, but a study of early- and mid-20th century cookbooks is an interesting endeavor to pursue. It should be noted, however, that in researching cookbooks, it’s important to consider the gender and race of the cookbook author and what the “most popular” cookbooks in any given decade can tell us about American life at the time.

The classic format we see here is title, a list of ingredients, and the steps to follow. You can see, however, that even Ms. Farmer assumes a certain level of competence in her reader. The recipe for Forest Hall Corn Sticks asks you to add hominy, to which you have already added butter, milk, and egg. Modern recipes would likely tell you to add the butter, milk, and egg to the hominy, then set aside and continue until it’s needed again.

I’m going to skip ahead here, but a study of early- and mid-20th century cookbooks is an interesting endeavor to pursue. It should be noted, however, that in researching cookbooks, it’s important to consider the gender and race of the cookbook author and what the “most popular” cookbooks in any given decade can tell us about American life at the time.

For more great posts on cookbooks, check out the best cookbooks for your cookbook club; 15 Funny Cookbooks; and 12 Essential Southern Cookbooks.

The First Cookbook

Get ready, y’all: we’re going back to tablets. The oldest recorded recipes—so, what we could call the oldest cookbook on record—are the Yale Tablets. This is a set of four clay tablets written in 1700 BC. They contain a recipe for meat stew, and actually a team replicated the recipe at an exhibition at NYU in 2018. The recipe uses meat, vinegar, smoked wood, and herbs, and is reminiscent of sikbāj, a meat stew that Dan Jurafsky describes in his book, The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu. “Sikbāj must have been amazingly delicious,” Jurafsky writes, “because it was a favorite of kings and concubines for at least 300 years, and celebrated in story after story.” Does this mean that modern-day pot roast or braised meat has its roots in ancient Mesopotamia? In a sense, yes. Jurafsky delineates a tradition from sikbāj (made with meat) to a form of sikbāj made with fish. The first recipe for that fish sikbāj comes in a 13th century medieval Egyptian cookbook, but by then the fish was dredged in flour, fried, and “sauced with vinegar and honey and spices” (Jurafsky, 2014). From here the recipe moves west, and the fried fish of sikbāj evolves into what we have come to know as fish and chips. From clay tablets with hearty meat stews in ancient Mesopotamia, to fried fish and chips, we can see that recipes take on a life of their own as people move them from place to place, as technology develops for new cooking methods, and as different ingredients become more or less readily available.The First Cookbook In English

The first cookbook in English was Forme of Cury, which was written by the chefs of King Richard II in 1390 (Jurafsky, 2014). Dan Jurafsky takes us through a linguistic study of different food words that appear in that book, their translations or movements in and through different languages (English, Latin, French), and how those words eventually become the words we use today, like soup or supper.

An emphasis here is interesting: clay tablets made up the world’s first cookbooks, and the stew contained therein was a favorite of kings for hundreds of years. The first English cookbook was written for King Richard II. As time went on, however, cookbooks switched from a record of the nobility to instruction for the common man.

The first cookbook in English was Forme of Cury, which was written by the chefs of King Richard II in 1390 (Jurafsky, 2014). Dan Jurafsky takes us through a linguistic study of different food words that appear in that book, their translations or movements in and through different languages (English, Latin, French), and how those words eventually become the words we use today, like soup or supper.

An emphasis here is interesting: clay tablets made up the world’s first cookbooks, and the stew contained therein was a favorite of kings for hundreds of years. The first English cookbook was written for King Richard II. As time went on, however, cookbooks switched from a record of the nobility to instruction for the common man.

Early American Cookbooks

Which brings us to the first cookbook written by an American, American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons in 1796. Now, the inscription here says that this cookbook has been “adapted to this country and all grades of life.” But let’s be clear: in 1796, all grades of life were not purchasing cookbooks. However, it continued to be printed and reprinted for more than 30 years before it fell off the radar. It has been reclaimed and studied now as a foundation text in American history (SmithsonianMag.com, 2018).

While this early history is great, it’s important that we jump forward a bit. You may have noticed a very distinct difference in the format and appearance of say, American Cookery, and one of this year’s top cookbooks, Indian-ish.

Which brings us to the first cookbook written by an American, American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons in 1796. Now, the inscription here says that this cookbook has been “adapted to this country and all grades of life.” But let’s be clear: in 1796, all grades of life were not purchasing cookbooks. However, it continued to be printed and reprinted for more than 30 years before it fell off the radar. It has been reclaimed and studied now as a foundation text in American history (SmithsonianMag.com, 2018).

While this early history is great, it’s important that we jump forward a bit. You may have noticed a very distinct difference in the format and appearance of say, American Cookery, and one of this year’s top cookbooks, Indian-ish.

It’s obvious that with the progression forward in publishing, printing, mass production, and diversity, we are now in a very different culinary publishing landscape. So let’s move on from the early, foundational texts, into the cookbooks that formed our modern understanding, and expectation, of cookbooks.

It’s obvious that with the progression forward in publishing, printing, mass production, and diversity, we are now in a very different culinary publishing landscape. So let’s move on from the early, foundational texts, into the cookbooks that formed our modern understanding, and expectation, of cookbooks.

The Cookbook Format

Before cookbooks lined our shelves, cooks learned by observation. Watching older relatives cook provided the necessary education for how to manage a hearth, an oven, how to prepare food to feed a family. Now, I must pause here because an important part of American history is deeply rooted in food. Slaves in America were the purveyors of food, so much so that after the Civil War ended and Reconstruction was underway, white women found that they had no idea how to prepare food because that skill bank and that knowledge base had moved away. While not all cooks in America prior to the Civil War were slaves, it’s crucial that we recognize that the need for culinary education came not just from people wanting to learn to cook, but from people needing to do so, and that necessity was a result of the subjugation of an entire race of people. When we talk of an American cuisine, and specifically Southern cuisine, we are talking about a way of eating that was developed and prepared by African slaves. The first cookbook authored by an African American was A Domestic Cookbook: Containing a Careful Selection of Receipts for the Kitchen by Mrs. Malinda Russell, published in 1866. It’s interesting that American Cookery specifies the author is “an orphan,” where Mrs. Malinda Russell is specifically characterized as “an experienced cook.” She came from a family of freed slaves, and her experience as a cook no doubt comes from that family history. She worked as a cook, later kept a boarding house and a pastry shop, and then left the South for Michigan, where she learned even more in her cooking. Her cookbook focuses primarily on pastries.

The format of her recipes follows the common format of many 19th century recipes in that the cookbook author assumes a certain amount of competence on the part of the reader (McLoone, 2016). Take a look at this recipe for Cream Cake from Russell’s book:

The first cookbook authored by an African American was A Domestic Cookbook: Containing a Careful Selection of Receipts for the Kitchen by Mrs. Malinda Russell, published in 1866. It’s interesting that American Cookery specifies the author is “an orphan,” where Mrs. Malinda Russell is specifically characterized as “an experienced cook.” She came from a family of freed slaves, and her experience as a cook no doubt comes from that family history. She worked as a cook, later kept a boarding house and a pastry shop, and then left the South for Michigan, where she learned even more in her cooking. Her cookbook focuses primarily on pastries.

The format of her recipes follows the common format of many 19th century recipes in that the cookbook author assumes a certain amount of competence on the part of the reader (McLoone, 2016). Take a look at this recipe for Cream Cake from Russell’s book:

The title is followed by the ingredients in the order that they should be followed. Here, however, we also see that the author leaves certain matters to the cook: the number of eggs, the amount of lemon flavor. This was common in cookbooks of the time, but it lays the groundwork for the recipe format to come just 30 years later.

Moving into the 20th century, access to education and the written word; ability to mass produce books; and a shift in the balance of who cooks, for whom, and with what agency all affected how Americans ate. Advances in technology also played a huge part in our culinary history. Consider that at one point, we didn’t have standard measuring spoons or cups. Stoves were lit by fire, which is hard to regulate, followed (thankfully) by gas and then electric. All of which helped to standardize the logistics of cooking, but we needed a cookbook that accomplished the same thing.

The title is followed by the ingredients in the order that they should be followed. Here, however, we also see that the author leaves certain matters to the cook: the number of eggs, the amount of lemon flavor. This was common in cookbooks of the time, but it lays the groundwork for the recipe format to come just 30 years later.

Moving into the 20th century, access to education and the written word; ability to mass produce books; and a shift in the balance of who cooks, for whom, and with what agency all affected how Americans ate. Advances in technology also played a huge part in our culinary history. Consider that at one point, we didn’t have standard measuring spoons or cups. Stoves were lit by fire, which is hard to regulate, followed (thankfully) by gas and then electric. All of which helped to standardize the logistics of cooking, but we needed a cookbook that accomplished the same thing.

Fannie Mae Farmer’s The Boston Cooking School Cookbook was published in 1896 and exhibits the modern recipe format that we know today. Farmer’s goal was to create recipes that could be consistently replicated in any home kitchen. She was well-known also for her radio show about cooking, and she ran The Boston Cooking School. Her cookbook was the first of many of its kind, and its format is one we have built on.

Fannie Mae Farmer’s The Boston Cooking School Cookbook was published in 1896 and exhibits the modern recipe format that we know today. Farmer’s goal was to create recipes that could be consistently replicated in any home kitchen. She was well-known also for her radio show about cooking, and she ran The Boston Cooking School. Her cookbook was the first of many of its kind, and its format is one we have built on.

The classic format we see here is title, a list of ingredients, and the steps to follow. You can see, however, that even Ms. Farmer assumes a certain level of competence in her reader. The recipe for Forest Hall Corn Sticks asks you to add hominy, to which you have already added butter, milk, and egg. Modern recipes would likely tell you to add the butter, milk, and egg to the hominy, then set aside and continue until it’s needed again.

I’m going to skip ahead here, but a study of early- and mid-20th century cookbooks is an interesting endeavor to pursue. It should be noted, however, that in researching cookbooks, it’s important to consider the gender and race of the cookbook author and what the “most popular” cookbooks in any given decade can tell us about American life at the time.

The classic format we see here is title, a list of ingredients, and the steps to follow. You can see, however, that even Ms. Farmer assumes a certain level of competence in her reader. The recipe for Forest Hall Corn Sticks asks you to add hominy, to which you have already added butter, milk, and egg. Modern recipes would likely tell you to add the butter, milk, and egg to the hominy, then set aside and continue until it’s needed again.

I’m going to skip ahead here, but a study of early- and mid-20th century cookbooks is an interesting endeavor to pursue. It should be noted, however, that in researching cookbooks, it’s important to consider the gender and race of the cookbook author and what the “most popular” cookbooks in any given decade can tell us about American life at the time.

Cookbooks and the Food Blog

This is where I have a bone to pick with everybody. You’ve likely seen gifs that dunk on food bloggers: “I don’t want to read about how your study abroad in Italy changed your life, just tell me how to make a balsamic reduction!” Just, everybody: chill. Here’s the thing: when food blogging started, it was revolutionary. We had been watching food happen on TV for years at that point, but that was on TV. Those people were professionals. But people like Ree Drummond and Molly Wizenberg and Deb Perelman? They were like us! (Okay, Ree Drummond is a stretch in the “just like us” category.) The point is, the lay person was writing about food in a way that was engaging and helpful. It’s important to note something that Deb Perelman pointed out earlier this year: food blogging was mostly done by women. To silence those stories, to actively grumble about having to listen to a woman’s story, is insulting. If you just want a recipe, open a cookbook or a recipe app.Now, I want to point out a stylistic shift that happened because of food bloggers. This is my un-researched but possibly solid theory: the Pioneer Woman changed the game on cookbook photography. What she was able to do on her blog—with control over photography, format, and editing—was show a home cook the step by step process of how a dish is made. What it looks like at each step. Close-up photography that holds the reader’s hand is a far cry from Fannie Farmer or Mrs. Malinda Russell, who both assumed some culinary literacy on the part of their reader. But Ree Drummond, with The Pioneer Woman Cooks—and like her, Deb Perelman, of Smitten Kitchen—anticipated a generation of home cooks who didn’t instinctively know how to mince garlic or whether the sauce is supposed to look like that. On the topic of photography, one of the other big departures from our early recipes is the presence of photography. Even in cookbooks that just use a stylized photo of the end result, there is nice color photography to entice you to attempt a recipe.2. It's mostly women telling these stories. Congratulations, you've found a new, not particularly original, way to say "shut up and cook." [I just don't see don't see the same pushback when male chefs write about their wild days or basically anything. Do you?] /4

— deb perelman (@debperelman) February 16, 2019

Cookbooks and Story

A final note about format: the headnote. The headnote is that little paragraph at the beginning of a recipe in a cookbook. An author might share a preparation tip, or tell you what they adapted it from. Indeed, they might go all food blogger on you and tell you about the birth of their child and why this dish mattered to them. But the headnote marks a change in cookbooks that I think is worth paying attention to: the headnote introduces story. Perhaps the biggest change in cookbook publishing is that we are a people who had the option to walk away from cooking as our ancestors knew it. Following World War II, with the advances in mass production and food preservation, the American family had many more options when it came to cooking. Shortcuts were manufactured: some good, some not. But when we choose cooking—whole food cooking—despite the shortcuts available, we’re choosing the old way. The storied way. And the stories behind the recipes we choose, the ways that we eat, matter. They mattered in ancient Mesopotamia, they mattered in the the Antebellum and Reconstruction South, they mattered after World War II, and they matter now.For more great posts on cookbooks, check out the best cookbooks for your cookbook club; 15 Funny Cookbooks; and 12 Essential Southern Cookbooks.