100 Must-Read Classics by People of Color

Classic literature can teach us so much about the past—how people lived, what they thought, and what they wanted to change. But the literary canon tends to be dominated by white men. I have nothing against Charles Dickens, Nathaniel Hawthorne, George Orwell, and the like, but there’s so much more for lovers of classics to read. We can expand the canon to include classics by people of color from all over the world, and I’ve assembled this list to help us all do just that.

For the purposes of this list, I’ve defined a classic as a book that’s at least 50 years old. Some of these classics by people of color are well-known and others are known only to scholars of the period they’re from. There are novels, plays, poetry, and nonfiction from around the world—something for everyone. If you’re doing the Read Harder Challenge, you’ll find lots of options for a classic by a person of color.

If you’re looking for classics by women, check out my previous list, and you’ll find more classics by people of color on Rebecca’s list for the Read Harder Challenge. There is some overlap between the three lists, but I’ve tried to keep this to a minimum. I’ve also avoided giving authors more than one slot on this list.

Books on this list are arranged in chronological order, and descriptions are from Goodreads. Take a look. See any of your favorites? Any classics by people of color that you’d add?

The Analects by Confucius (476). “A collection of Confucius’ sayings, compiled by his pupils shortly after his death in 497 B.C., and they reflect the extent to which Confucius held up a moral ideal for all men.”

One Thousand and One Nights by Anonymous (800). “These are the tales that saved the life of Shahrazad, whose husband, the king, executed each of his wives after a single night of marriage.”

The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon (1002). “Moving elegantly across a wide range of themes including nature, society, and her own flirtations, Sei Shōnagon provides a witty and intimate window on a woman’s life at court in classical Japan.”

The Diary of Lady Murasaki by Murasaki Shikibu (1008-1010). “The Diary recorded by Lady Murasaki (c. 973 c. 1020), author of The Tale of Genji, is an intimate picture of her life as tutor and companion to the young Empress Shoshi.”

Theologus Autodidactus by Ibn Al-Nafis (1277). “This work, written sometime between 1268 and 1277, is one of the first Arabic novels, may be considered an early example of a science fiction, and an early example of a coming of age tale and a desert island story.”

The Confessions of Lady Nijō by Lady Nijō (1307). “A tale of thirty-six years (1271-1306)in the life of Lady Nijō, starting when she became the concubine of a retired emperor in Kyoto at the age of fourteen and ending, several love affairs later, with an account of her new life as a wandering Buddhist nun.”

On Love and Barley by Bashō Matsuo (late 1600s). “Bashō’s haiku are the work of an observant eye and a meditative mind, uncluttered by materialism and alive to the beauty of the world around him.”

Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio by Pu Songling (1740). “In his tales of shape-shifting spirits, bizarre phenomena, haunted buildings, and enchanted objects, Pu Songling pushes the boundaries of human experience and enlightens as he entertains.”

Phyllis Wheatley, Complete Writings by Phyllis Wheatley (1761). “This volume collects both Wheatley’s letters and her poetry: hymns, elegies, translations, philosophical poems, tales, and epyllions—including a poignant plea to the Earl of Dartmouth urging freedom for America and comparing the country’s condition to her own.”

Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano by Olaudah Equiano (1789). “The first slave narrative to attract a significant readership reveals many aspects of the eighteenth-century Western world through the experiences of one individual.”

The Golden Days (The Story of the Stone, part 1) by Cao Xueqin (1791). “This rich, magical work sets worldly events—love affairs, sibling rivalries, political intrigues, even murder—within the context of the Buddhist understanding that earthly existence is an illusion and karma determines the shape of our lives.”

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas (1845). “Dumas’ epic tale of suffering and retribution, inspired by a real-life case of wrongful imprisonment, was a huge popular success when it was first serialised in the 1840s.”

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass (1845). “Douglass’ own account of his journey from slave to one of America’s great statesmen, writers, and orators is as fascinating as it is inspiring.”

Narrative of Sojourner Truth by Sojourner Truth (1850). “Truth recounts her life as a slave in rural New York, her separation from her family, her religious conversion, and her life as a traveling preacher during the 1840s.”

Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup (1853). “Perhaps the best written of all the slave narratives, Twelve Years a Slave is a harrowing memoir about one of the darkest periods in American history.”

Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter by William Wells Brown (1853). “A fast-paced and harrowing tale of slavery and freedom, of the hypocrisies of a nation founded on democratic principles, Clotel is more than a sensationalist novel.”

Biography of an American Bondman, By His Daughter by Josephine Brown (1855). “Josephine Brown (1839-?).was the youngest child of the abolitionist and author William Wells Brown (1814-1862).and his wife Elizabeth. She was moved to finish the book when she discovered that her father’s autobiography was out of print.”

Our Nig by Harriet E. Wilson (1859). “The tale of a mixed-race girl, Frado, abandoned by her white mother after the death of the child’s black father.”

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs (1861). “A rare firsthand account of a courageous woman’s determination and endurance, this inspirational story also represents a valuable historical record of the continuing battle for freedom and the preservation of family.”

The Curse of Caste, or The Slave Bride by Julia C. Collins (1865). “The first novel ever published by a black American woman, it is set in antebellum Louisiana and Connecticut, and focuses on the lives of a beautiful mixed-race mother and daughter.”

Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House by Elizabeth Keckley (1868). “Traces Elizabeth Keckley’s life from her enslavement in Virginia and North Carolina to her time as seamstress to Mary Todd Lincoln in the White House during Abraham Lincoln’s administration.”

Life Among the Paiutes: Their Wrongs and Claims by Sarah Winnemucca (1883). “Sarah Winnemucca, daughter of a Paiute chief, presents in her autobiography a Native American viewpoint on the impact of whites settling in the West.”

Wynema: A Child of the Forest by S. Alice Callahan (1891). “The first novel known to have been written by a woman of American Indian descent. … it tells the story of a lifelong friendship between two women from vastly different backgrounds—Wynema Harjo, a Muscogee Indian, and Genevieve Weir, a Methodist teacher from a genteel Southern family.”

Iola Leroy by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1892). “The story of the young daughter of a wealthy Mississippi planter who travels to the North to attend school, only to be sold into slavery in the South when it is discovered that she has Negro blood.”

A Chinese Ishmael and Other Stories by Sui Sin Far (1896). “Fictional stories about Chinese Americans, first published in 1896, were a reasoned appeal for her society’s acceptance of working-class Chinese at a time when the United States Congress maintained the Chinese Exclusion Act.”

Hawai’i’s Story by Hawai’i’s Queen by Queen Lili’uokalani (1898). “Possibly the most important work in Hawai’ian literature, Hawai’i’s Story is a poignant plea from Hawai’i’s queen to restore her people’s kingdom.”

Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South by Pauline Hopkins (1900). “Like Harriet Beecher Stowe, Pauline Hopkins writes of the injustices suffered by blacks at the hands of whites. But her novel penetrates deeper than Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Up From Slavery by Booker T. Washington (1900). “Washington reveals his inner most thoughts as he transitions from ex-slave to teacher and founder of one of the most important schools for African Americans in the south, The Tuskegee Industrial Institute.”

The Heart of Hyacinth by Onoto Watanna (1903). “The coming-of-age story of Hyacinth Lorrimer, a child of white parents who was raised from infancy in Japan by a Japanese foster mother and assumed to be Eurasian.”

The Souls of Black Folk by WEB Du Bois (1903). “Du Bois penned his epochal masterpiece … in 1903. It remains his most studied and popular work; its insights into life at the turn of the 20th century still ring true.”

I Am a Cat by Natsume Sōseki (1905). “The chronicle of an unloved, unwanted, wandering kitten who spends all his time observing human nature—from the dramas of businessmen and schoolteachers to the foibles of priests and potentates.”

The Soul of the Indian by Charles Alexander Eastman (1911). “Brings to life the rich spirituality and morality of the Native Americans as they existed before contact with missionaries and other whites.”

The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson (1912). “Narrated by a man whose light skin allows him to ‘pass’ for white, the novel describes a pilgrimage through America’s color lines at the turn of the century.”

The Home and the World by Rabindranath Tagore (1916). “Set on a Bengali noble’s estate in 1908, this is both a love story and a novel of political awakening. The central character, Bimala, is torn between the duties owed to her husband, Nikhil, and the demands made on her by the radical leader, Sandip.”

The Plays of Georgia Douglas Johnson by Georgia Douglas Johnson (1920s). “This volume collects twelve of Georgia Douglas Johnson’s one-act plays. … As an integral part of Washington, D.C.’s, thriving turn-of-the-century literary scene, Johnson hosted regular meetings with Harlem Renaissance writers and other artists, including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, May Miller, and Jean Toomer, and was herself considered among the finest writers of the time.”

American Indian Stories by Zitkala-Sa (1921). “One of the most famous Sioux writers and activists of the modern era, Zitkala-Sa (Gertrude Bonnin) recalled legends and tales from oral tradition and used experiences from her life and community to educate others about the Yankton Sioux.”

A Dark Night’s Passing by Naoya Shiga (1921). “Tells the story of a young man’s passage through a sequence of disturbing experiences to a hard-worn truce with the destructive forces within himself.”

The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China by Lu Xun (1921). “Lu Xun is arguably the greatest writer of modern China, and is considered by many to be the founder of modern Chinese literature. Lu Xun’s stories both indict outdated Chinese traditions and embrace China’s cultural richness and individuality.”

Selected Poems of Gabriela Mistral by Gabriela Mistral (1922). “Poems by the late Chilean poet who, in 1945, became the first Latin American author to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.”

Cane by Jean Toomer (1923). “A literary masterpiece of the Harlem Renaissance, Cane is a powerful work of innovative fiction evoking black life in the South.”

The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran (1923). “A collection of poetic essays that are philosophical, spiritual, and, above all, inspirational.”

There Is Confusion by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1924). “Traces the lives of Joanna Mitchell and Peter Bye, whose families must come to terms with an inheritance of prejudice and discrimination as they struggle for legitimacy and respect.”

Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey Or, Africa for the Africans by Marcus Garvey (1924). “The most famous collection of Garvey’s speeches and essays.”

The New Negro edited by Alain Locke (1925). “From the man known as the father of the Harlem Renaissance comes a powerful, provocative, and affecting anthology of writers who shaped the Harlem Renaissance movement and who help us to consider the evolution of the African American in society.”

Chaka by Thomas Mofolo (1925). “Tells the classic story of the Zulu hero Chaka.”

The Weary Blues by Langston Hughes (1926). “Hughes spoke directly, intimately, and powerfully of the experiences of African Americans, at a time when their voices were newly being heard in our literature.”

Rashomon and Other Stories by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (1927). “Writing at the beginning of the twentieth century, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa created disturbing stories out of Japan’s cultural upheaval.”

Quicksand by Nella Larsen (1928). “Larsen’s powerful first novel has intriguing autobiographical parallels and at the same time invokes the international dimension of African American culture of the 1920s.”

Some Prefer Nettles by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (1928). “It is a tale of sexual passion and disorientation that explores modern Japan’s conflict between the values of Western culture and Occidental tradition.”

Home to Harlem by Claude McKay (1928). “With sensual, often brutal accuracy, Claude McKay traces the parallel paths of two very different young men struggling to find their way through the suspicion and prejudice of American society.”

My People the Sioux by Luther Standing Bear (1928). “A landmark in Indian literature, among the first books about Indians written from the Indian point of view by an Indian.”

The Blacker the Berry by Wallace Thurman (1929). “One of the most widely read and controversial works of the Harlem Renaissance, The Blacker the Berry was the first novel to openly explore prejudice within the Black community.”

My Soul’s High Song: The Collected Writings of Countee Cullen by Countee Cullen (1920s-1940s). “A generous introduction to new readers of Countee Cullen and a more than generous offering to those of us who hold the poet dear.”

Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells by Ida B. Wells (1930s). “This engaging memoir tells of her private life as mother of a growing family as well as her public activities as teacher, lecturer, and journalist in her fight against attitudes and laws oppressing blacks.”

Black No More by George S. Schuyler (1931). “What would happen to the race problem in America if black people turned white? Would everybody be happy? These questions and more are answered hilariously in Black No More, George S. Schuyler’s satiric romp.”

Jonah’s Gourd Vine by Zora Neale Hurston (1934). “Tells the story of John Buddy Pearson, ‘a living exultation’ of a young man who loves too many women for his own good.”

Native Son by Richard Wright (1940). “Tells the story of a young black man caught in a downward spiral after he kills a young white woman in a brief moment of panic.”

Love in a Fallen City by Eileen Chang (1943). “Written when Chang was still in her twenties, these extraordinary stories combine an unsettled, probing, utterly contemporary sensibility, keenly alert to sexual politics and psychological ambiguity, with an intense lyricism that echoes the classics of Chinese literature.”

Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges (1944). “The seventeen pieces in Ficciones demonstrate the whirlwind of Borges’s genius and mirror the precision and potency of his intellect and inventiveness, his piercing irony, his skepticism, and his obsession with fantasy.”

Where There’s Love, There’s Hate by Silvina Ocampo and Adolfo Bioy Casares (1946). “Both genuinely suspenseful mystery fiction and an ingenious pastiche of the genre, the only novel co-written by two towering figures of Latin American literature.”

The Street by Ann Petry (1946). “The poignant, often heartbreaking story of Lutie Johnson, a young black woman, and her spirited struggle to raise her son amid the violence, poverty, and racial dissonance of Harlem in the late 1940s.”

The President by Miguel Ángel Asturias (1946). “A story of a ruthless dictator and his schemes to dispose of a political adversary in an unnamed Latin American country usually identified as Guatemala.”

The Living Is Easy by Dorothy West (1948). “One of only a handful of novels published by black women during the forties, the story of ambitious Cleo Judson is a long-time cult classic.”

The Tunnel by Ernesto Sabato (1948). “Sabato’s first novel is framed as the confession of the painter Juan Pablo Castel, who has murdered the only woman capable of understanding him.”

No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai (1948). “The poignant and fascinating story of a young man who is caught between the breakup of the traditions of a northern Japanese aristocratic family and the impact of Western ideas.”

Nisei Daughter by Monica Sone (1952). “A Japanese American woman tells how it was to grow up on Seattle’s waterfront in the 1930s and to be subjected to ‘relocation’ during World War II.”

The Palm-Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola (1952). “Drawing on the West African (Nigeria), Yoruba oral folktale tradition, Tutuola described the odyssey of a devoted palm-wine drinker through a nightmare of fantastic adventure.”

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1952). “As he journeys from the Deep South to the streets and basements of Harlem, from a horrifying ‘battle royal’ where black men are reduced to fighting animals, to a Communist rally where they are elevated to the status of trophies, Ralph Ellison’s nameless protagonist ushers readers into a parallel universe that throws our own into harsh and even hilarious relief.”

Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin (1953). “With lyrical precision, psychological directness, resonating symbolic power, and a rage that is at once unrelenting and compassionate, Baldwin chronicles a fourteen-year-old boy’s discovery of the terms of his identity as the stepson of the minister of a storefront Pentecostal church in Harlem one Saturday in March of 1935.”

The Dark Child by Camara Laye (1954). “A distinct and graceful memoir of Camara Laye’s youth in the village of Koroussa, French Guinea.”

The Sound of Waves by Yukio Mishima (1954). “A timeless story of first love. It tells of Shinji, a young fisherman and Hatsue, the beautiful daughter of the wealthiest man in the village.”

Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz (1956). “The first novel in Nobel Prize-winner Naguib Mahfouz’s magnificent Cairo Trilogy, an epic family saga of colonial Egypt that is considered his masterwork.”

The Waiting Years by Fumiko Enchi (1957). “In a series of colorful, unforgettable scenes, Enchi brilliantly handles the human interplay within the ill-fated Shirakawa family.”

Memoirs of a Woman Doctor by Nawal El Saadawi (1958). “Rebelling against the constraints of family and society, a young Egyptian woman decides to study medicine, becoming the only woman in a class of men.”

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe (1958). “Tells two overlapping, intertwining stories, both of which center around Okonkwo, a ‘strong man’ of an Ibo village in Nigeria.”

Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids by Kenzaburō Ōe (1958). “Recounts the exploits of 15 teenage reformatory boys evacuated in wartime to a remote mountain village where they are feared and detested by the local peasants.”

The Guide by R. K. Narayan (1958). “Formerly India’s most corrupt tourist guide, Raju—just released from prison—seeks refuge in an abandoned temple. Mistaken for a holy man, he plays the part and succeeds so well that God himself intervenes to put Raju’s newfound sanctity to the test.”

Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall (1959). “This beloved coming-of-age story set in Brooklyn during the Depression and World War II follows the life of Selina Boyce, a daughter of Barbadians immigrants.”

A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry (1959). “Hansberry’s award-winning drama about the hopes and aspirations of a struggling, working-class family living on the South Side of Chicago connected profoundly with the psyche of black America—and changed American theater forever.”

Down Second Avenue by Es’kia Mphahlele (1959). “A landmark book that describes Mphahlele’s experience growing up in segregated South Africa. Vivid, graceful, and unapologetic, it details a daily life of severe poverty and brutal police surveillance under the subjugation of an apartheid regime..”

God’s Bits of Wood by Ousmane Sembène (1960). “In 1947-48 the workers on the Dakar-Niger railway came out on strike. This novel is an imaginative evocation of how those long days affected the lives of people who lived along the hundreds of miles of track.”

The Ambiguous Adventure by Cheikh Hamidou Kane (1961). “This long-unavailable classic tells the tale of young Samba Diallo, a devout pupil in a Koranic school in Senegal whose parents send him to Paris to study philosophy.”

A House for Mr Biswas by V.S. Naipaul (1961). “When he marries into the domineering Tulsi family on whom he indignantly becomes dependent, Mr. Biswas embarks on an arduous–and endless–struggle to weaken their hold over him and purchase a house of his own.”

The Woman in the Dunes by Kōbō Abe (1962). “After missing the last bus home following a day trip to the seashore, an amateur entomologist is offered lodging for the night at the bottom of a vast sand pit. But when he attempts to leave the next morning, he quickly discovers that the locals have other plans.”

Selected Poems by Gwendolyn Brooks (1963). “Showcases an esteemed artist’s technical mastery, her warm humanity, and her compassionate and illuminating response to a complex world.”

A Backward Place by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (1965). “Six colourful, comic characters inhabit A Backward Place. All but one are Westerners who have come to Delhi to experience an alternative way of life.”

The Interpreters by Wole Sowinka (1965). “The Nobel Laureate’s first novel spotlights a small circle of young Nigerian intellectuals living in Lagos.”

The Autobiography of Malcolm X by Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley (1965). “In this riveting account, he tells of his journey from a prison cell to Mecca, describing his transition from hoodlum to Muslim minister.”

The River Between by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1965). “Christian missionaries attempt to outlaw the female circumcision ritual and in the process create a terrible rift between the two Kikuyu communities on either side of the river.”

Efuru by Flora Nwapa (1966). “Efuru, beautiful and respected, is loved and deserted by two ordinary undistinguished husbands.”

A Handful of Rice by Kamala Markandaya (1966). “The novel depicts the hard struggle of life in a modern city and its demoralization. Ravi , son of a peasant, joins in the general exodus to the city, and, floating through the indifferent streets, lands into the underworld of petty criminals.”

The Doctor’s Wife by Sawako Ariyoshi (1966). “This novel is really two stories: on the one hand, the successful medical career of Hanaoka Seishu, the first doctor in the world to perform surgery for breast cancer under a general anesthetic; on the other hand, the lives of his wife and his mother, who supported him with stoic resignation, even to the extent of finally volunteering to be used as guinea pigs in his experiments.”

Jubilee by Margaret Walker (1966). “Tells the true story of Vyry, the child of a white plantation owner and his black mistress. Vyry bears witness to the South’s antebellum opulence and to its brutality, its wartime ruin, and the promises of Reconstruction.”

The Time of the Hero by Mario Vargas Llosa (1966). “Set among a community of cadets in a Lima military school, it is notable for its experimental and complex employment of multiple perspectives.”

Black Rain by Masuji Ibuse (1966). “The story of a young woman who was caught in the radioactive ‘black rain’ that fell after the bombing of Hiroshima.”

Houseboy by Ferdinand Oyono (1966). “Toundi Ondoua, the rural African protagonist of Houseboy, encounters a world of prisms that cast beautiful but unobtainable glimmers, especially for a black youth in colonial Cameroon.”

Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih (1966). “A rich and sensual work of deep honesty and incandescent lyricism. In 2001 it was selected by a panel of Arab writers and critics as the most important Arab novel of the twentieth century.”

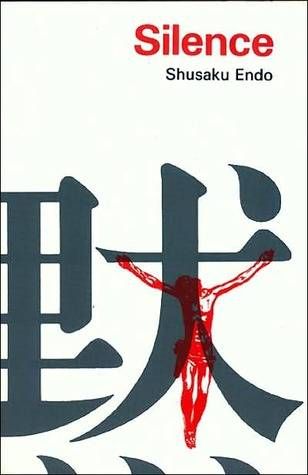

Silence by Shūsaku Endō (1966). “Father Rodrigues is an idealistic Portuguese Jesuit priest who, in the 1640s, sets sail for Japan on a determined mission to help the brutally oppressed Japanese Christians and to discover the truth behind unthinkable rumours that his famous teacher Ferreira has renounced his faith.”

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Márquez (1967). “Tells the story of the rise and fall, birth and death of a mythical town of Macondo through the history of the Buendia family.”

Thousand Cranes by Yasunari Kawabata (1967). “While attending a traditional tea ceremony in the aftermath of his parents’ deaths, Kikuji encounters his father’s former mistress, Mrs. Ota. At first Kikuji is appalled by her indelicate nature, but it is not long before he succumbs to passion.”

What are your favorite diverse classic books?