Our Stories to Tell: Reflections on Nadja Spiegelman’s Memoirs

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Each person has a story to tell, and their side. Our memories prove unreliable alone. We need to talk to people, to gather facts and sources. Ultimately, we grasp parts of the truth when discussing the past.

We need this perspective to approach Nadja Spiegelman’s memoirs, I’m Supposed to Protect You from All This. Nadja is Art Spiegelman’s daughter, and Art wrote Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, a comic memoir of his parents surviving the Holocaust.

Each person has a story to tell, and their side. Our memories prove unreliable alone. We need to talk to people, to gather facts and sources. Ultimately, we grasp parts of the truth when discussing the past.

We need this perspective to approach Nadja Spiegelman’s memoirs, I’m Supposed to Protect You from All This. Nadja is Art Spiegelman’s daughter, and Art wrote Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, a comic memoir of his parents surviving the Holocaust.

First an Asterisk

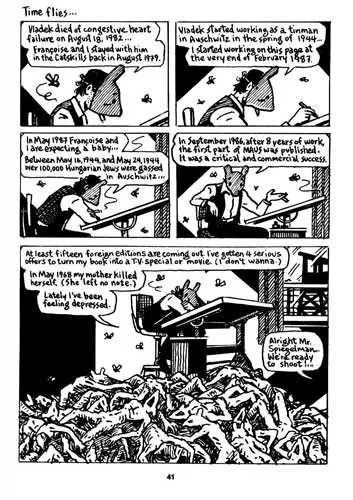

In Maus, Nadja wasn’t even born. Art refers to her in a footnote, after he talks to the press about Maus. She lampshade this in her memoirs. Art later added her thoughts in the MetaMaus edition Maus tells Vladek’s story of surviving the Holocaust, and Art’s attempts to survive his father, whose miserly ways appear more irritating than whimsical. Francoise in the story appears as one of the sane people because she and her parents exist peripherally to Art’s stress. She discusses the flaws in Art’s portrayal of animals as allegories for different nationalities, due to her being French and Jewish. Art also uses Francoise to embody the hope that their generation can make happiness out of the ashes of their past.

Maus tells Vladek’s story of surviving the Holocaust, and Art’s attempts to survive his father, whose miserly ways appear more irritating than whimsical. Francoise in the story appears as one of the sane people because she and her parents exist peripherally to Art’s stress. She discusses the flaws in Art’s portrayal of animals as allegories for different nationalities, due to her being French and Jewish. Art also uses Francoise to embody the hope that their generation can make happiness out of the ashes of their past.

Another Side

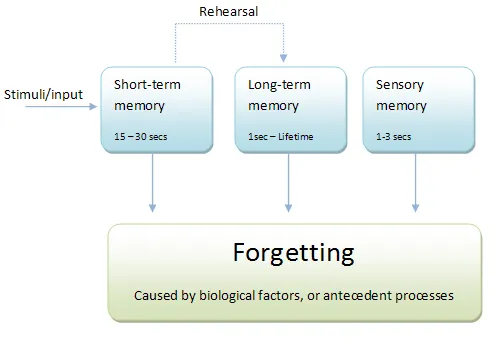

Nadja’s memoirs tell a different story. She adds depths to her mother, showing Francoise’s flaws, virtues, and a cycle that Francoise inadvertently passed on to her daughter. Nadja’s words hope to break that cycle by chronicling it. She verifies the truth in what she and her family remembers. Telling stories seems important for the Spiegelman family. They want to capture people on the page as they are, not as flat cardboard cutouts. Nadja, for example, discusses how her great-grandmother Mina was jailed for collaboration with the Nazis but always protected her child. Her grandmother Josee was nasty to Francoise, but also rescued her daughter from a suicide attempt. Josee also protests when Nadja describes Mina as a collaborator. The women flit through different worlds, contained within Paris and New York. Nadja’s story also concerns itself with truth. She acknowledges that memory is unreliable, and that it’s possible to make mistakes about what happened and who was at a certain place. Using oral history of her mother’s side of the family proves interesting, for example. Francoise tends to contradict what she sees as wrong. Nadja has to fight against this unintentional gaslighting. Arguments with her mother didn’t help. It’s almost like reading a prose version of Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoirs, where she discusses how her narrative appears unreliable, and that she uses photographs and diary entries to confirm what was real or not real.

Nadja’s story also concerns itself with truth. She acknowledges that memory is unreliable, and that it’s possible to make mistakes about what happened and who was at a certain place. Using oral history of her mother’s side of the family proves interesting, for example. Francoise tends to contradict what she sees as wrong. Nadja has to fight against this unintentional gaslighting. Arguments with her mother didn’t help. It’s almost like reading a prose version of Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoirs, where she discusses how her narrative appears unreliable, and that she uses photographs and diary entries to confirm what was real or not real.