At the Heart of the Tale: What Makes Stories Poised for Retelling

Many times, when my family has gathered for big events — birthdays, holidays, and other celebrations — there’s been an abundance of retellings. We know these stories in and out; we can map the punchlines and surprises from a mile away. And yet we still ask for them until someone takes the helm and tells the story again. And again. After years, these stories have become their own adaptations and retellings. Maybe we adjust the dialogue a little bit, or omit parts that are no longer relevant or memorable. We’ll adjust the story to match the tone of the group attending, or the mood of the event. But the core events stay the same.

Arguably, any good story is poised for retelling. Great stories, though, can be retold across the ages, molded to fit its listeners/readers in the times they’re in.

A Recipe for Retellings

But what makes a great story worth retelling? There are some influencing factors.

I’ve been reading The Penguin Book of Mermaids for research lately, and the introduction touched on how fairytales and mythologies are similar across cultures:

Since ancient times, humans have notes that stories from discrete cultures around the world can be remarkably similar, and have tried to account for why the same motifs and themes occur globally…What bears keeping in mind is that the value of stories is not the degree to which they are authentically native, but the ways that they reflect the concerns or values of the group who tells and retells them.

Cristina Bacchilega and Marie Alohalani Brown Brown, from The Penguin Book of Mermaids

The last line really gets at the core of what stories are good for retelling; they can be molded to fit the topics of the times, adjusted, and even improved upon.

Additionally, I believe retellings have the ability to perfect the original fairytale, myth, or legend, especially if the original’s first message is clearly outdated. In Marie-Louise Von Franz’s book The Interpretation of Fairy Tales, she writes, “we can see that in being handed on, fairytales need not necessarily degenerate but may just as well improve.”

The examples I include below are such contemporary improvements. The authors take a fairytale and sculpt it be a fleshed out, glowing entity of our day and age. These examples may very well become inspiration for retelling in their own right, 25, 50, and 75 years from now.

Extracting Content for Retelling

For the sake of specificity and clarity, I’d like to focus on one of my favorite fairytales that has been retold time and time again and will showcase its contemporary retellings.

“Bluebeard” is arguably the most famous fairytale of Charles Perreault, published in the late 1600s. For those unfamiliar, it tells the tale of a wealthy man who is in the habit of murdering his wives. The latest wife attempts to avoid the fate of her predecessors. There are other iterations to this tale, such as “The Robber Bridegroom.” Some folklorists describe “Bluebeard” as a tale about the dangers of female curiosity. Others have also said that it’s about rebelling against patriarchal systems (i.e. the wives do not obey their husband, and the last wife is able to overcome and end his murderous cycle).

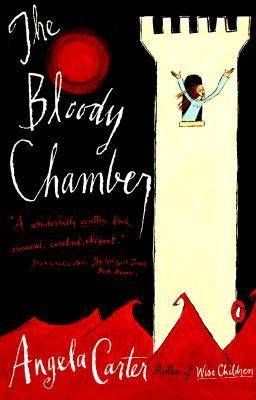

One of the most famous retellings of “Bluebeard” (and my favorite of all time) comes in the form of Angela Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber.” It’s found in her collection under the same title, The Bloody Chamber. The story follows a budding young woman who marries a mysterious wealthy man. She’s swept away to his castle, where she is given keys but told not to use a particular one. My favorite character in Carter’s story is the woman’s mother, who senses her daughter’s distress and arrives in the magnificent ending of justice and female power. Carter wrote the collection in 1979, in the midst of Second Wave Feminism. Carter said of her collection:

My intention was not to do ‘versions’ or, as the American edition of the book said, horribly, ‘adult’ fairytales, but to extract the latent content form the traditional stories and to use it as the beginnings of new stories.

From Novelists in Interview by John Haffenden (1985)

Carter’s intention, to me, really nails what an effective retelling can do: extracts content poised for development and making something new with it. Carter gave the curious wife a history and a concerned mother. Perhaps even more importantly, the concerns and values Carter had writing the story played an important role in what made “The Bloody Chamber” the successful and timeless retelling that it is.

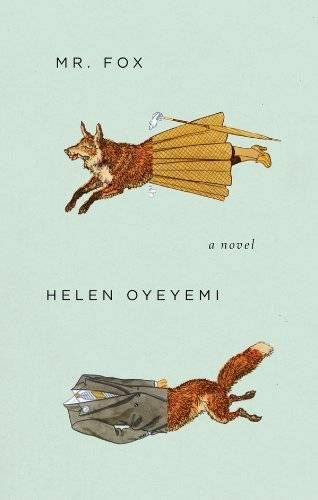

Another excellent retelling of Bluebeard is Helen Oyeyemi’s captivating novel, Mr. Fox, which was published in 2011. Bluebeard can be found in the titular character. He is a writer who is in the habit of killing off his heroines in gruesome fashion. However, Mr. Fox’s muse Mary accuses him of avoiding real connection by killing his heroines and challenges him to explore further.

Mr. Fox is wonderfully told in stories within stories and stories reacting to stories. Whereas Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber” is gothic and atmospheric, Oyeyemi’s Mr. Fox is game-like and charming. Yet they are essentially retellings of the same story. (If you’re interested in more of Helen Oyeyemi’s wonderful writing, I’d love to point you to my Reading Pathway on her work.)

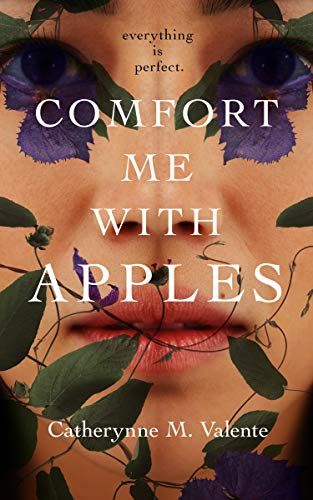

Predictions for Future Bluebeard Retellings

The story of Bluebeard is one that is going to be retold time and time again. It was just retold in the recent November 2021 release Comfort Me With Apples by Catherynne M. Valente, a novella that is a mix of Bluebeard and biblical retellings. It’s a quick, cutthroat novella that is its own animal of retelling. The way the story’s rules are set and the setting reflect much of today’s wealthy, gated communities. It also constantly toys with the definition of perfection, of happiness, and what one deserves.

I can see Bluebeard retold far into the future, molded in new ways to fit the values and concerns of the time. I can see the above contemporary titles being retold as they become new fixtures in the fairytale canon.

In the future, I’d love to see a Bluebeard retelling told in climate crisis, or perhaps a retelling focusing more on body autonomy, the effects of capitalism, etc. Regardless, I will be ready to devour each retelling in all its glory.

The Future of Retellings

In addition to classic fairytales like Bluebeard continuing to being retold, there are popular contemporary stories that may experience have their own retellings far into the future. Books that captured our imagination in the past decade may be altered and retold to fit the current times, especially in regards to climate crisis, capitalism, and the brittle political landscape. From YA series to to award-winning books, here are a couple types of stories I can see being retold in the upcoming generations:

Stories like The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

I chose The Hunger Games as an example, but I any think arena/competition stories where violence is used as a means of entertainment and/or monetary success will always be dissected. As we continue to dive into the digital age, the question of how far we’re willing to go — how much we’re willing to sacrifice — to achieve monetary success or simply being entertained will always be explored and retold. Other stories in this category might include the show Squid Game, the YA books Caraval and Where Dreams Descend, among others.

Stories like Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler

Parable of the Sower is part of the solarpunk genre, which is explained in Emily Wenstrom’s brilliant introduction. In short, Wenstrom writes “the spirit of solarpunk is one of craftsmanship, egalitarianism, and optimism where technology can be put to work to solve our greatest problems.” This is the other side of the coin to The Hunger Games retellings, where stories will be retold with optimism for technology, solutions to our growing climate crisis (or, in the event climate crisis is irreversible, solution by means of space exploration), and a better future for humanity.

The Opportunity for Retellings

Be it popular YA series or mainstays of genres like solarpunk, many stories have the opportunity to be retold, depending on the author’s values and the values of society at the time. Stories will be will be retooled and retold to better predict our future, and reflect our hardships. They’ll reignite interest in the original stories, and create new paths, new angles, for more retellings by new generations of writers.

Also In This Story Stream

- Why Romance Will Never Stop Retelling Cinderella and Beauty and the Beast

- The Best Gender-Flipped Retellings

- Retellings That Haven’t Happened But Should

- Retellings Keep the Classics Relevant

- How ELLA ENCHANTED by Gail Carson Levine Helped Teach Me to Read

- A More Inclusive Happy Ending: Romance Novels That Diversify the Classics

- Retellings of Asian Myths, Epics, and Folklore

- Dark Retellings of Children’s Classics

- Why Retellings of Classics From Authors of Color and Queer Authors Matter