Love, Independence, Punishment, Murder: Summer Camp in YA Fiction

I went to day camp from about 2nd grade through 8th grade. It was a religious summer camp, despite the fact then — and now —I’m areligious, but it was a way for me to socialize with other kids, get outside, and free my grandparents from a few hours of watching me. I loved it wholeheartedly, and though the option to stay overnight was one, I never took it. Instead, I stuck to singing Jesus songs, enjoying afternoon swims in the pool (including going off the diving board and conquering a fear as soon as I passed the advanced swimming test in 4th grade), and playing camp-wide games of capture the flag and red rover before heading home, sun-battered and chlorine-covered. I read my fair share of tween and teen summer camp stories during that time, and while summer camp in YA has definitely changed since the ’90s, one thing remains the same: camp is a killer setting and remains a popular spot for teens to fall in love, to experience heartbreak, and maybe to help solve a murder or two.

What is camp, anyway? It might involve camping or the wilderness, or it might not. Camp is less about hiking and biking and getting into the lake (like camping) and more about an organized summer program that’s supervised by older teens and adults. Camp has often served as a bridge for childcare during the months when young people are out of school but parents are still working. While it once was fairly focused on being set outdoors in some capacity, whether it was a day camp or a sleep away camp, it’s common now to see a million different types of camp. Some may never include being outside at all and instead focus entirely on a specific skill or craft for a designated period of time.

Camp Before YA Became YA

YA did not become a category until the ’60s, with the publication of The Outsiders. But that didn’t mean there were not books for teens being published prior — in fact, the first “real” YA book for teens is commonly cited as Maureen Daly’s Seventeenth Summer, a romantic read that is still in publication today.

Because scouting was popular among young people in the early 1900s through the 1940s, it isn’t a surprise that some of the fiction written for this demographic would involve camp. Often it was camping, as opposed to summer camp, but summer camp showed up as well.

Early camp-set stories of this era include The High School Boys in Summer Camp by H. Irving Hancock (part of a longer series of stories featuring main character Dick Prescott), The Meadow-Brook Girls Under Canvas; or Fun and Frolic in the Summer Camp by Janet Aldridge, and Scatter: Her Summer at Girls Camp by Leslie Warren (dedicated to a real summer camp). All three are adventure-focused, with young teens at the helm. The themes and topics addressed align with what the literature of the time for this demographic looked like.

The Campfire Girls was a long-running and popular series of books about scouting written from the mid 1910s through the mid 1930. The books rotated among a number of authors and several took place at camp (and the Girls took part in plenty of camping as well). Campfire Girls targeted female readers and was a precursor to popular series like Nancy Drew. Again, these were primarily adventure stories, and camp provided a perfect avenue to allow girls to seek out just enough challenges to tell a story without breaking them of their gender roles.

Camp Independence and Responsibility and Camp Don’t-Wanna-Be-Here

Camp counseling was once a coveted gig in the teen world, if the fiction of the ’80s and ’90s is any indication. Books like the Camp Counselors series by Diana Ames played into the same romantic ideals that Nickelodeon shows like Hey Dude and Salute Your Shorts of the time did. Ames’s series offered tweens and teens the opportunity to imagine falling in love and breaking hearts. It harkened back to some of the camp books of the ’80s, including titles like Camp Girl-Meets-Boy by Caroline B. Cooney, and what made this era of YA camp books stand apart from earlier camp-themed series like the late-’80s Camp Sunnyside Friends by Marilyn Kaye was that teens were the ones in charge — not the ones being led.

Being a camp counselor, in addition to offering the opportunity for love, is indicative of maturity and independence. Where cars have always been symbolic of freedom, camp counseling offered an even broader arena of possibility: there is little adult oversight, there is money to be made, and it’s not always limited to the financial privilege of transportation.

Camp counseling, much like camp itself, is the adolescent experience in a microcosm. It’s time away from home, away from school, and away from everyone who knows you. Camp lets you enter a chrysalis, with the hope of emerging as a newer, better person at the end.

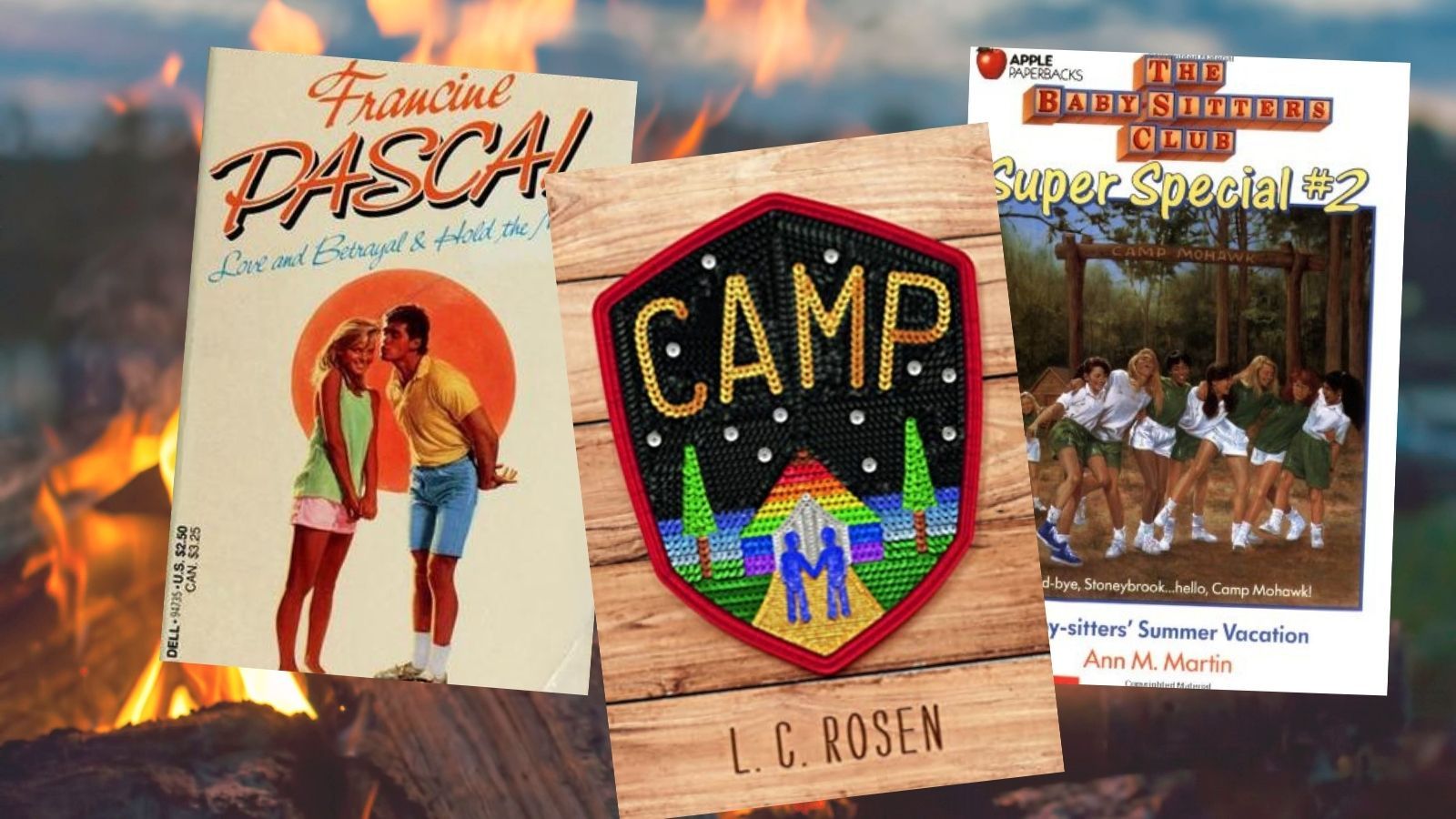

Not all of the camp jobs were as counselors, though. Francine Pascal entered the camp sphere with a story about Victoria in Love and Betrayal and Hold the Mayo, who works as a camp waitress 200 miles from home. She’s excited for the job, but it turns out the gig isn’t what she expected, and she might be falling for someone who is entirely unavailable.

Sometimes, the reasons teens took jobs at camp was because of their life experiences. Lurlene McDaniel, mother of the so-called “sick lit” category of fiction, did just this. Dawn, in So Much to Live For, is a two-time cancer survivor and agrees to take a job at the summer camp she and her best friend attended. She wants to be an inspiration for the younger campers who are struggling with their own health challenges. The problem is camp is not the same without her best friend who died.

For Marcy, the main character in Paula Danziger’s There’s a Bat in Bunk Five, being invited to be a counselor for a teacher’s creative arts camp seems like the perfect chance to let go of the shy and insecure girl she once was. It’s unfortunate, though, that the campers will be a challenge and more, that she can’t get rid of some of the fundamental parts of herself, even in a new setting. She’ll have to instead learn to embrace and honor who she is, as she is.

The summer camp experience changed quite a bit during the ’80s and ’90s, too. No longer were the stories primarily about adventure. Certainly, adventures happened, but now camp meant the possibility of not only love, but also death, betrayal, and other darkness.

Brock Cole’s 1987 cult classic The Goats is an example of when camp goes wrong — very wrong. Following a boy and a girl who are stripped and sent to a small island by a group of campers who are participating in “just a tradition,” the two stranded teens are unable to get help. . . and maybe, as it turns out, they quite like life on their own. Another dark tale from the ’80s is Steven Kroll’s Breaking Camp, a The Chocolate War-esque story of cruel initiation.

Other camp stories in the ’80s and ’90s not as easy to connect thematically included Hail, Hail Camp Timberwood by Ellen Conford, about a teen who doesn’t want to be shipped off to summer camp and dreads being forced to be around such young kids, especially as she begins to fall for the cute guy. The Summer War by Harry W. Paige took a teen through a horrifying experience of discovering buried skeletons at a camp in the Adirondacks, and when the ’00s rolled around, things got supernatural at camp with Beth Goobie’s Before Wings.

Camp Adventures in Series

One of the staples of book series in the ’80s and ’90s in particular was the volume that would take our beloved characters to camp. Whatever series you loved, somehow, they found their way to camp or camp found their way to them.

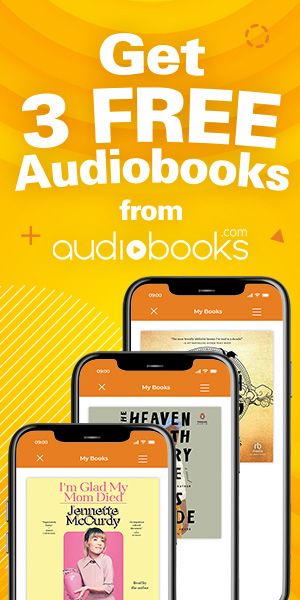

The members of The Baby-Sitters Club experienced both, first going to camp in The Baby-Sitters Summer Vacation — a super special edition — and then brought camp to Stoneybrook with Mary Anne and Camp BSC. The Pen Pals, a series of the early ’90s by Sharon Dennis Wyeth, also had their own super special dedicated to a coed camp in Summer Sizzle. It followed many of the same paths of other camp stories of the time, with romance, bravery, and (friendly) rivalry at the center. For the horse girls, Virginia Vail’s Riding Home took to a summer riding camp, and for readers who wanted a Christian lens for summer camp, there was Robin Jones Gunn’s Christy Miller in Seventeen Wishes. Preferred a pick-your-own adventure through summer camp? Elizabeth Carroll delivered in Summer Love, part of the “Dream Your Own Romance” line.

There was plenty to fear, as well, when it came to camp stories in beloved series books. Lights Out, the 12th book in RL Stine’s classic Fear Street series took us Camp Nightwing, where the body of a counselor was found and a junior counselor is determined to find the killer. Kate Clancy, the 14-year-old namesake of Lisa Eisenberg’s series, experiences an array of scary things at Camp Windingo (so close to Wendigo!) until she confronts a thief in Mystery at Camp Windingo.

And Meg Cabot, writing under her pseudonym Jenny Carroll, took her supernaturally-powered Jess Mastriani (nickname: Lightning Girl) to camp. Jess worked a camp for musically-talented kids — not her dream gig — but she may not have been anticipating her role in helping solve the disappearance of a young girl. Code Name Cassandra is the second in the 1-800 Series.

Fat Camp

Not all teens want to be at camp, as seen in several of the titles above, but worse, teens being forced into camps that actively harm them was not uncommon in older YA titles. What’s disturbing is how 30 years ago, fat camp was a popular theme in camp stories and in a way that didn’t depict fat camp as a humiliating and dangerous experience.

It’s hard not to read these book descriptions and wonder how much they impacted an entire generation’s perceptions on body image and fatness. The ’90s and ’00s were rife with diet culture, thanks to the since-discredited CDC report that opened the floodgates to the “obesity epidemic,” but even prior to that, young children were taught to equate thinness with worthiness (and, to be sure, these stories only seemed to feature good white kids at the center).

I Was a 15-Year-Old Blimp, published in 1985, is Gabby’s story. She becomes obsessed with her weight, trying on some of the fad diets she’s heard about, including the “Stewardess diet” of grapefruit and hard-boiled eggs. In her pursuit of thinness, she develops an eating disorder and — this is not a joke and taken directly from the book’s cover flap — gets sent to fat camp to better manage her weight. It is, reportedly, very funny that she’s there and loses weight, only to come home and realize there’s more to life than being thin.

Abigail doesn’t fare a whole lot better in Joyce St. Peter’s Always, Abigail, where she finds herself expelled from fat camp in the summer between her 12th and 13th birthday. She ends up at a dude ranch instead in this 1981 book.

1983 also brought Slim Down Camp by Stephanie Manes. This one, which the reviews all call hilarious, is about Sam and Belinda, who meet at Camp Thin-na-Yet. The goal: a summer of weight loss. But what the two of them want is escape, not a Saturday night dance with celery sticks. Even if it undermines the premise, the book’s cover is enough to leave a sour taste in the mouths of contemporary readers who see the way in which a fat teen is villainized.

Maybe he didn’t go to fat camp, per se, but when the fat kid gets out of camp, it’s a story, too. Robert Lipsyte’s One Fat Summer features Bobby, who is depicted as out of control at 200 pounds, get out of summer camp for the first time this year because summer camp has always been torture (he’s fat, you know?). But it’s no better not at camp, when he’s forced to deal with a bully. This book was, remarkably, made into a film in 2018.

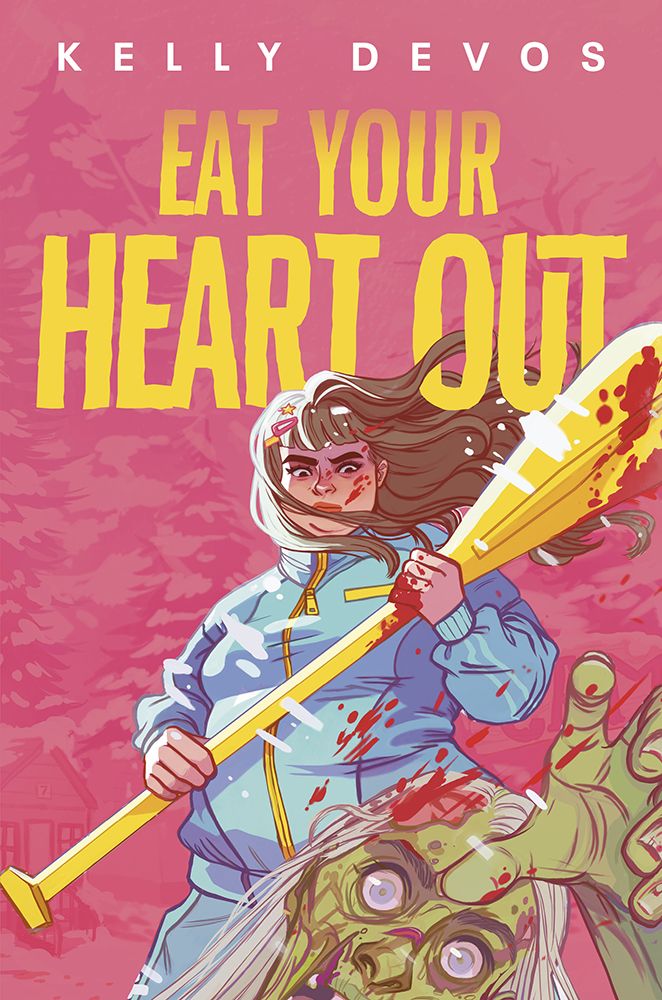

Fat camp has petered out as a setting in the last few decades, though Kelly DeVos’s Eat Your Heart Out gives teens the chance to battle the zombies at Camp Featherlite in 2021. It’s a take on the genre that’s part Shaun of the Dead and part Dumplin‘. And damn, if Vivian gets to wield the power on the cover.

Although not fat camps, another deeply hurtful style of camp emerged in YA during the last 15 years: queer conversion camps. But I’m a Cheerleader may have been a forerunner to stories that dismantle the philosophies and groups behind such camps, but for today’s teen readers, there are even more stories that explore this traumatic experience. Among them are The Miseducation of Cameron Post by emily m. danforth and The Summer I Wasn’t Me by Jessica Verdi.

Do Diverse Camps Exist?

If it seems like camp stories feature a lot of white kids, that’s because camp stories feature a lot of white kids. Camp stories historically also feature a lot of straight kids. Fortunately, as YA continues to offer more diverse voices, so, too, do the stories and settings within the category.

Longtime writer for young adults and middle grade readers, Tanita S. Davis, wrote the Camp Chronicles. The two book series, published in 1999 and 2000 respectively, followed 16-year-old Danni at her first job at a summer camp. Danni, depicted as white on the cover, does seem to engage with a diverse group of teens, particularly in her second year at camp. The short-lived series allowed a Black author to pen a camp story and though it was not starring a character of color, it did not fall into the poor Black kids trope.

Cynthia Leitich Smith’s 2001 YA book Rain Is Not My Indian Name was also a forerunner in diverse camp settings. Rain is encouraged by her brother to attend her aunt’s Indian Camp (the terminology used in the book). While reluctant at first, she finds herself wanting to get more involved and better understand her own heritage, especially when the local city counsel threatens to end funding for the program.

First published in the Netherlands in 1999, the beloved queer romance story The Days of Bluegrass Love by Edward van de Vendel just hit shelves in the U.S. (translated by Emma Rault). The book follows Tycho, a boy who has mostly drifted through his life. He’s decided to make a change. His plan? Work as a camp counselor in the U.S. for international kids. Tycho meets Oliver, another counselor, and the two find their hearts filled with one another. Why it took over 20 years for the book to make it to the country where it’s set can only be assumed, but likely, a small market for translated works, paired with an under-marketed, under-funded, and unsafe environment for openly queer love stories until recent history meant teens who had similar experience had to wait. And wait. And, eventually, become 30 year olds.

Lev Rosen brings queer camp to the forefront in his recent and aptly named Camp, another contemporary read bringing LGBTQ+ love stories to the forefront in camp lit.

In her novel Not Now, Not Ever, Lily Anderson not only offers space for a girl of color to attend camp — a nerdy academic one – but throughout the book, the lack of inclusive camps is actively questioned and pursued. That book, like Sandhya Menon’s When Dimple Met Rishi offer hope for not only a diverse array of camps (Menon’s characters are taking part in a coding camp) but more camp stories starring and populated by Black, Brown, Indigenous, Latine, and other people of the global majority.

Contemporary Camp

Much like YA as a whole has become more diverse, so, too, have camp stories. But in addition to becoming more diverse, camp stories have become much more complex, nuanced, and — perhaps — more authentic to the contemporary teen experience. The stories are often darker or unravel deep secrets, or they put teens into wholly new and potentially uncomfortable territory. Camps have also become more mysterious in and of themselves, offering what might be an incredible opportunity for escape or a terrifying journey into the unknown.

Sunny Song Will Never Be Famous by Suzanne Park gives us a teen sent to a tech detox camp, while Emma Lord’s You Have A Match uses camp as a place for two sisters who discovered one another via DNA to meet. Readers itching for murder, deception, and mystery will find plenty to keep the pages turning in camp-set books like The Counselors by Jessica Goodman, Dig Two Graves by horror mistress Gretchen McNeil, Camp So-and-So by Mary McCoy, and Julia Lynn Rubin’s Primal Animals.

And, of course, there’s still plenty of love and romance in contemporary camp, too. Swoon along with those first fluttery feelings, those first kisses, and (sometimes) first heartbreaks in titles like Serena Kaylor’s Long Story Short, Sunkissed by Kasie West, and The Matchbreaker Summer by Annie Rains.

Summer Camp Never Goes Cold

Though this look at summer camp in YA doesn’t dig into comics, certainly graphic novels and graphic memoirs for teens feature plenty of camp stories (think Lumberjanes or Honor Girl, among others). It is impossible to explore every book or nuance, every format or title that has come, gone, or will remain staples. But much like summer itself, camp stories never get old, as they offer teens a space to explore who they are, to take on new leadership roles, to escape adult supervision, and to become the hero/ines of their own stories.