8 Courtly Medieval Female Writers

It’s safe to say that most readers have grown up with a healthy dose of the legends of King Arthur, the great British king who went on an epic quest for the Holy Grail and was eventually laid to rest in Avalon. But where did King Arthur live in the time between? Well, it was none other than the famous court of Camelot, where he and his knights conferred at the Round Table.

Courtly intrigue is fascinating to modern audiences. It is far more romantic than the machinations of Washington played out on C-SPAN. At least medieval courts had knights, wizards, and fealty, which are far more romantic than congressional hearings and pardoning turkeys.

Medieval Courts Through the Eyes of Women

That said, almost all the legends of King Arthur are male-centric, with the two key female characters—Morgan le Fay and Queen Guinevere—being pigeon-holed as evil sorceress and adulteress, respectively. To be frank, their stories have almost always been told by men.

Unfortunately, despite his iconic status, King Arthur’s life is simply a legend, meaning that we’ll never know the true nature of the women at his court. Fortunately, there were plenty of (real) female courtiers who lived in various medieval courts and penned everything from histories to poems. Thanks to them, we can at least have a female perspective of court life beyond the male gaze.

Female Writers From Medieval Japan

Medieval Japan saw the rise of feudalism and is generally broken into two major periods: Kamakura (1185–1333) and Muromachi (1336–1573). The Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1600) is sometimes included.

Medieval Japanese literature continued the classical tradition of monogatari (court fiction) and waka poetry, which is court poetry from the 6th century to 14th century. Many female writers were noblewoman who were acclaimed poets with their own merits. However, much of their lives went unrecorded, hence the ambiguity surrounding their respective births and deaths.

Ben no Naishi (possibly 1228–1270)

Ben no Naishi (possibly 1228–1270)

Notable work: Sacred Rites in Moonlight: Ben No Naishi Nikki

Ben no Naishi was a naishi (female courtier) who served in the court of Emperor Go-Fukakusa, the 89th emperor of Japan. She is famous for her memoir Sacred Rites in Moonlight: Ben No Naishi Nikki but is also regarded as an accomplished poet.

Kenreimon-in Ukyō no Daibu (possibly 1157–1233)

Notable work: Kenreimon-in Ukyō no Daibu Shū

Kenreimon-in Ukyō no Daibu served Taira no Tokuko, the Empress-consort of Emperor Takakura, from 1173 to ~1178. Twenty-three of her poems were included in chokusen wakashū (imperial Japanese anthologies of waka poetry), and she also completed her personal anthology Kenreimon-in Ukyō no Daibu Shū.

Princess Shikishi (1149 –1201*)

Princess Shikishi (1149 –1201*)

Notable work: String of Beads: Complete Poems of Princess Shikishi

Princess Shikishi was the thirrd daughter of Emperor Go-Shirakawa, the 77th Emperor of Japan. She never married, and served at Kamo Shrine, a Shinto sanctuary complex in Kyoto. She eventually left the shrine and became a Buddhist nun. Most of Princess Shikishi’s poems are in a form called tanka, which groups syllables in a set of 5-7-5-7-7. Her talent led to her poetry being included in 15 of 21 imperial anthologies. A prolific poet, 399 of her poems are recognized today.

*Although Princess Shikishi is regarded as a classical poet, I am including her in our list of medieval writers since her life extended well into the early Kamakura period (which began in 1185).

Kaki Mon’in (unknown–1380s)

Notable work: Kaki Mon’in Go-shū

Kaki Mon’in was a noblewoman, Buddhist nun, and waka poet of the Nanboku-chō period (1336–1392), which occurred at the very beginning of the wider Muromachi period (1336–1573). At court, she served as the concubine of Emperor Go-Murakami, the 97th emperor of Japan and was the mother of Emperor Go-Kameyama, the 99th emperor of Japan (some sources suggest that she was also the mother of Emperor Chōkei, the 98th emperor of Japan).

Her private collection of waka poetry, Kaki Mon’in Go-shū, is regarded as a valuable resource on the accession of Emperor Chōkei. Seventeen poems from this private collection were included in the Shin’yō Wakashū, an important 14th century anthology.

Female Writers From Medieval Europe

The time period of medieval Europe, known as the Middle Ages, generally begins with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ends at the Renaissance. Traditionally, the Middle Ages are broken into 3 periods: Early (i.e. the Dark Ages) from the 5th century to 10th century; High from 1000 to ~1300; and Late from 1250 to 1500. Like medieval Japan, much of medieval Europe was ensconced in feudalism.

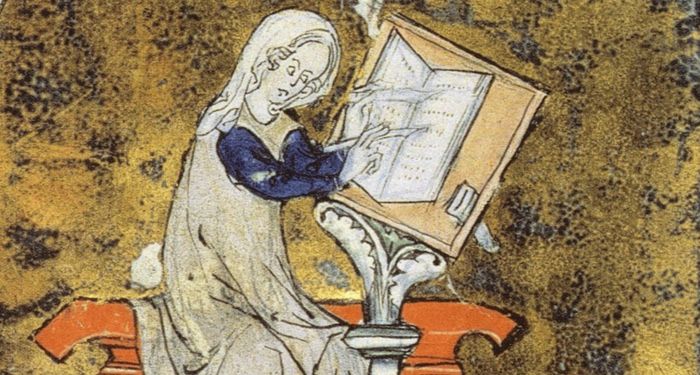

During the Middle Ages, literature was primarily composed of religious works along with some secular works. The reason religious work was so prominent (and well preserved) is because clerics ran intellectual life; therefore, it was clerics who produced most of the writing. A good amount of secular works, at least those still preserved, were written by nobles and courtiers who provided accounts of life at court, histories, and even some translations.

Marie de France (1160–1215)

Marie de France (1160–1215)

Notable work: Lais of Marie de France

Country: England (but possibly born in France)

Marie de France was a poet who lived in England and was most likely born in France. Almost nothing is known about her life; historians are even unsure which court she lived and wrote at. However, she was known in the royal court of King Henry II of England.

Marie de France is regarded as the first woman to write in francophone, a Romance language of the Indo-European family. She also knew Latin, Middle English, and (possibly) Breton. Her claim to fame is being the author of the Lais of Marie de France, which strongly influenced romantic and heroic literature.

Leonor López de Córdoba (1362–1420)

Leonor López de Córdoba (1362–1420)

Notable work: Memorias

Country: Spain

Leonor López de Córdoba was a Spanish noblewoman best known for her autobiography aptly names Memorias. Her parents were Martin López de Córdoba and Sancha Carrillo, who were well-connected to the Spanish royal family.

In 1403, Leonor López de Córdoba resided in the court of Henry III of Castile and became an advisor to his queen Catherine of Lancaster; however, de Córdoba was banished from the court after falling out of favor. Her writing has a place in history because Memorias is the believed to be the earliest autobiography written in Spanish. That said, there is evidence to suggest that she dictated the work to a notary.

Christine de Pizan (1364–1430)

Christine de Pizan (1364–1430)

Notable work: Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (The Book of the City of Ladies)

Country: France (but born in Venice, Italy)

Christine de Pizan was a poet and writer in the court of King Charles VI of France. She was born in Venice, Italy, but moved to France after her father accepted an appointment as an astrologer in the court of Charles V.

Christine de Pizan is famous for her defense of women in Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (The Book of the City of Ladies), which is actually her formal response to Roman de la Rose (The Romance of the Rose) by Jean de Meun. His sensual language and imagery drew criticism from de Pizan. In Le Livre de la Cité des Dames, she describes an allegorical city of “Dames” who each served as its building blocks.

Anna Comnena (1083–1153)

Anna Comnena (1083–1153)

Notable work: The Alexiad

Country: Byzantine Empire (born in Constantinople, which is modern-day Istanbul, Turkey)

Anna Comnena had a pretty eventful life. Born on December 1, 1083 to none other than Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and his wife Irene Doukaina, she is infamous for her failed attempt to usurp her brother John II Komnenos.

Growing up, she was well-educated in Greek literature, history, philosophy, theology, mathematics, and medicine. The reason for her comprehensive education was that she and her fiancé were next in line for the Byzantine throne…until her brother, John II Komnenos, was born. When her father died in 1118, Anna Comnena and her mother failed to usurp the throne from John II Komnenos, who exiled his sister to a monastery. It was there that she wrote The Alexiad, an account of her father’s reign as emperor.

Also In This Story Stream

- 10 of the Best Medieval Romance Stories

- 10 Books With Our Favorite Fictional Knights

- 10 Great Medieval (and Medieval-ish) Mystery Books

- Get Spellbound By These Magical Medieval Fantasy Books

- 8 Great Medieval History Reads From East to West

- 8 Fascinating Characters From Arthurian Legend

- 9 Medieval Poets You Will Actually Enjoy Reading

- 6 of the Best Medieval Young Adult Books

- 3 of the Best Comics for Fans of Arthurian Legend