A Tiny History of Miniature Books

In 2013, Japanese publisher Toppan printed Shiki no Kusabana, flowers of season, a 22-page book that was 0.03 inches (or 0.75 mm) tall. According to the 2013 Telegraph article, it “contains names and monochrome illustrations of Japanese flowers such as the cherry and the plum.” This wasn’t the publisher’s first miniature book — they’ve been printing small books since 1964. Per the article, they are planning on approaching the Guinness Book of World Records to get the designation of smallest printed book. The book is part of a long tradition of printmaking of miniature books going as far back as the birth of printing.

I had the opportunity to talk with three experts about the history and use of these marvelous creations: Anne Bromer, president of Bromer Booksellers and author of Miniature Books: 4,000 Years of Tiny Treasures; Jill Gage, Custodian of the John M. Wing Foundation on the History of Printing and Bibliographer of British Literature and History at the Newberry Library; and Angel Aribal, the proprietor of Miniature Books USA. This is just a taste of the longer history.

What is a Miniature Book?

A miniature book is defined as a book about three inches tall, Bromer explained, noting that they can generally be read with the naked eye. There are even smaller books called micro-minatures that can be one and one-fourth inches but require a magnifying glass. They can be made in a variety of processes including printing, handprinting, or even using nanotechnology. Per the Telegraph, the smallest book as of 2013 was Teeny Ted from Turnip Town that “was .007mm x 0.010mm and the letters were carved into 30 microtablets on a polished piece of crystalline silicon.”

For this article, I’m focusing on printed copies including letterpress, since while nanotechnology and hi-tech is great, it’s fascinating to see how printing could go so small.

The Age of Printing Through the 18th Century

Miniature printed books have been around almost as long as the first printed books (miniature books have existed many centuries before printing came to the West). Bromer noted that there were miniature incunables (something printed before 1500) that were made only 20 years after the famous Gutenberg Bible. One of the earliest uses of miniature books was a learning activity for printers to give to their apprentices. It was a test of skills that they could set type, print the page, and then bind it. These books tended to be a little bigger than three inches, sometimes three and one-half to four and one-half inches tall, but given the technology at the time, it’s still very impressive.

Many of the earliest miniature books were religious in nature, Gage of the Newberry noted, like prayer books, Bibles, and psalters. “You might want to think about them as literally portable books or pocket books. Books that you could actually put in your pocket and walk around with,” Gage said, “What kind of thing might you want to have around you all of the time?” There were also religious books printed in Hebrew for Jewish faithful.

She also noted that italics was used in the 16th century to make books smaller, not for emphasis as we do today (also used in poetry), and thinner paper.

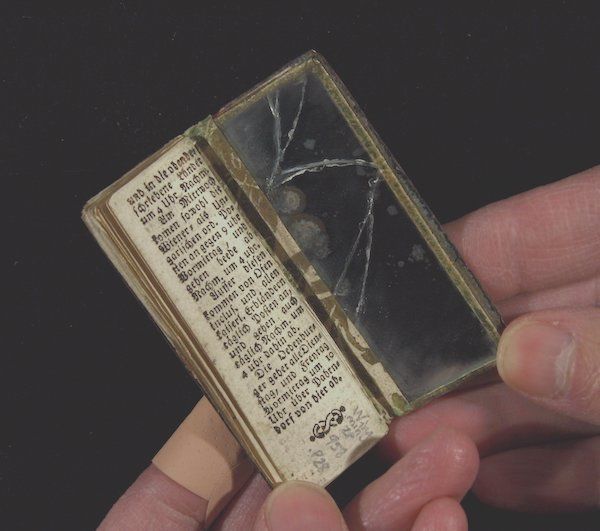

Gage further mentioned that people didn’t have as many books as we are accustomed to today. So these small books weren’t just collected because of curiosity, they were likely used. She does note that sometimes the books were to be shown off. One 1799 almanac for women, pictured below, has a nice enameled cover and a mirror. She explained: “I think it’s about seeing and being seen. Being able to pull out a book in public and what that means and kind of a show of your literary niche. The fact that you can just pull a book out of your pocket.”

That portability is key. Bromer said that Napoleon traveled with a miniature library of histories and classics while he went out conquering nations. Hard to pack light for a military campaign if you have massive volumes of books in your luggage!

Miniature books also were used by children. Bromer noted the printing of thumb Bibles for children: “these were very important in children being able to hold their own little abbreviated Bible” for church and learning how to read in the 17th century. These thumb Bibles were printed up through the 19th century. At the end of the 18th century, books started to be made and marketed towards children. That also brought about a boom in the classics read in school like Horace and Ovid.

The 19th Century

The 19th century is considered to be the real Golden Age of Miniature Books, Gage noted. It was more about technique, cutting type, and making plates. “A lot of it is kind of technology driven,” Gage said. Sets of children’s books were printed. Bromer noted that one of the first books on birth control was a miniature book called 1832 Fruits of Philosophy; or, the Private Companion of Young Married People by Charles Knowlton.

She also noted that tiny books of the Emancipation Proclamation were printed and given to Union soldiers to give out to enslaved African Americans. Madeline Zehnder in History Today explained that white abolitionist John Murray Forbes printed them in the hopes of using them as a recruitment tool.

Miniature Books in the 20th Century

In the 20th century, miniature books continued to be made and used. I was over the moon when I found out that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a famous collector of miniature books, amassing 750 of them, some gifts from Eleanor Roosevelt. They were eventually sold by auction. LiveAuctioneers sold an FDR Signed Miniature Book, “Little book of English History,” for $450 in 2020.

He’s not the only president to have engaged with little books. There was a miniature book for Theodore Roosevelt when he was campaigning, Bromer said. Many years later, President Gerald Ford worked with a printer in California, Bromer noted, to make two miniature books of his speeches, which he signed.

Even Marvel got into the act. According to BoingBoing, in 1966, they printed ⅝” by ⅞” mini books (think postage stamp sized) about your favorite superheroes: Spider-Man, Thor, Captain America, the Hulk, Nick Fury…and Millie the Model. Abrams is releasing them in a larger format to be enjoyed.

Even Buzz Aldrin brought mini books to the moon. Per the Clark University website, the books were called Robert Hutchings Goddard — Father of the Space Age, an autobiography of the man. Publisher Achille St. Onge, based in Worcester, sent them to Aldrin, hoping he could take both up and leave one on the moon. Alas, he could not leave anything behind, per protocol, so he brought both back. He gave one to Onge’s widow, who donated the book to Clark University, where it can be seen today.

However, in the 20th century, there became more of a trend of making miniature books not for use but as objects or for marketing purposes, Gage says, like printing them so small that they cannot be seen with the naked eye (or without a microscope). Bromer calls the trend “quirky” and “fun” but noted “I think this is sometimes why miniature books don’t get the respect that I think that they deserve. They were travel souvenirs. They were fables. There’s erotica in miniature, [cook books] and almost as many subjects as you can think of in full size books have been done in intimate format.”

Miniature Books Today

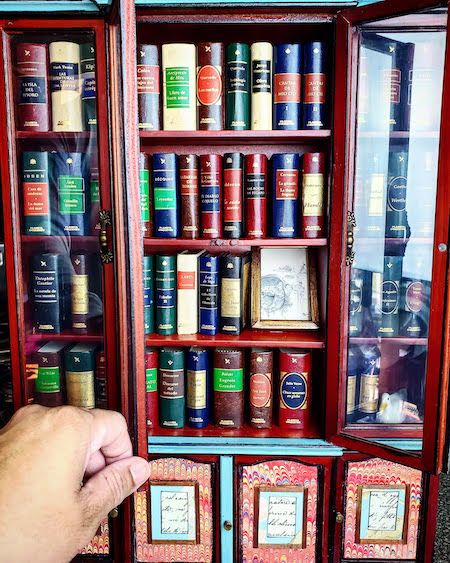

Miniature books are still being printed today. Miniature Books USA distributes miniature books based in Chicago. When asked why miniature books, Angel Aribal, proprietor of the company, he said, “I have been a collector of miniature books for more than a decade now and I have been friends with the owners of the biggest miniature book publishers and also some of the most talented minibook makers around the world. Eventually, I became their distributing partner as well.” They print everything from Alice in Wonderland, prayer books, and even a book of vintage erotic photography.

Aribal also offers an explanation for why these books remain popular: “Miniature stuff always fascinates us because it appeals to our inner child, raising our curiosity and immediately setting our minds into an imaginative and playful mood no matter how old or young you are.”

When asked the challenges of printing these books, Aribal said, “The fact that the tools you need to make a book needs to be miniaturized as well. So everything has to be custom made and learned on the fly. Formatting a book to fit into tiny pages also presents quite a difficult and tedious task.”

Bromer also commissioned some miniature books on a variety of subjects. They printed letterpress on handmade paper, bound, with illustrations/etchings and more. She explained: “The focus was not only to produce a miniature book, but to produce a miniature book that reflected the Book Beautiful, which is the main part of what we deal in.”

It’s nice to know that this incredible tradition of printed books continues to the present day.

This is meant to be a tiny history with a few highlights on some cool printed miniatures. Hopefully this whets your appetite for these tiny books.

For folks interested in seeing them in person, there are a few places. The Newberry Library in Chicago has miniature books, but not as a singular collection — they are part of other collections in their stacks. The Morgan Library, Boston Public Library, and Yale University Beinecke Rare Book Library are a few places to find more books though each place may have their own rules and regulations for how to look at them.

Want more about special and unique books? Here’s an essay about what I learned about the antiquarian book trade. Here’s another on how to become a rare book collector.