A GAME FOR SWALLOWS and Anne Frank: Narratives of Hidden Children

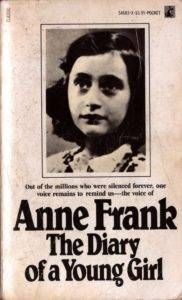

My stepdaughter and I started reading Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl when she was in fourth grade, but we had to stop every other page in order for me to explain the finer details of religion, world history, and human reproduction, and then the book disappeared from my nightstand. Now that she’s in seventh grade, she has a wider knowledge base, and it turned out the book had been jammed between the bed and the wall all that time, so we started over again.

My stepdaughter and I started reading Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl when she was in fourth grade, but we had to stop every other page in order for me to explain the finer details of religion, world history, and human reproduction, and then the book disappeared from my nightstand. Now that she’s in seventh grade, she has a wider knowledge base, and it turned out the book had been jammed between the bed and the wall all that time, so we started over again.

Around the same time we returned to “Sunday, 14 June, 1942,” recounting Anne’s thirteenth birthday, I picked up A Game for Swallows: To Die, to Leave, to Return by Zeina Abirached, which takes place over a single night in 1984, inside an apartment foyer in East Beirut. Zeina and her younger brother have never known a world that wasn’t fractured by war. In her memory, the bombings, snipers, bullet holes and barricades have always existed. A visit to their grandmother’s house, a few blocks away, has always involved running, sneaking, dodging bullets, and the possibility of death.

The family’s once-spacious apartment has effectively shrunk; the building’s residents have determined that that only truly safe space is the family’s foyer, which is where everyone congregates, especially when the bombardment begins. On the evening in question, the children’s parents have undertaken the treacherous journey to grandmother’s house, and, as the hour grows late and the parents do not return, the other adults in the building gather around, doing their best to create an atmosphere in which the children can feel safe.

Anne Frank, of course, had no such comfort. Although young, she had sufficient understanding of the political situation that she could not have been distracted from concern for her parents’ safety by the baking of a cake, as Zeina and her brother are. The adults around her are of no use when it comes to soothing, and Anne’s previous experience of the world makes her well aware of how much she’s less. With only limited contact from outside her Secret Annex, Anna was constantly peeking out from behind curtains, trying to catch a beam of sunlight or a breath of fresh air or a glimpse of those who still walked freely through the streets of Amsterdam. She recounts how important nature has become to her, and how the study of botany and the occasional glimpse of a tree must replace her natural longing to enjoy the outdoor world.

Anne Frank, of course, had no such comfort. Although young, she had sufficient understanding of the political situation that she could not have been distracted from concern for her parents’ safety by the baking of a cake, as Zeina and her brother are. The adults around her are of no use when it comes to soothing, and Anne’s previous experience of the world makes her well aware of how much she’s less. With only limited contact from outside her Secret Annex, Anna was constantly peeking out from behind curtains, trying to catch a beam of sunlight or a breath of fresh air or a glimpse of those who still walked freely through the streets of Amsterdam. She recounts how important nature has become to her, and how the study of botany and the occasional glimpse of a tree must replace her natural longing to enjoy the outdoor world.

Zeina uses the graphic medium to reconstruct the world outside, as it appeared to her during this period: a simple maze of safe and unsafe corners, of barricades that provided safety from the sniper, of dangerous crossing that must be made at top speed. Over and over again, the adults assure her that she is safe as long as she stays within the defined parameters. Anne is somewhat less assured that the Secret Annex is unassailable: her parameters include utter silence when strangers are in the building, periodic burglary scares, and the constant fear of betrayal. Her sense of the world outside the annex is even more fragmented. She hears the clock bells floating through the air and the bombs exploding, and she hungrily devours the news, and she peeks through the curtains, when no one can see.

At the end of Zeina’s story, the safety of the foyer is breached by a bomb; most of the people in her story are inspired to relocate immediately. Anne’s story ends when the annex is raided and its occupants send to concentration camps.

As the hidden children of World War II grew older, they added their narratives to Frank’s. For decades, most of these individuals maintained the silenced they had been taught during the war. Stay inside, make no noise, they learned. For the youngest readers, Patricia Polacco’s The Butterfly, presents the narrative of a girl learning that her mother has been hiding Jews when she meets a little girl who cannot resist the temptation of peeking out the window. Hidden: A Child’s Story of the Holocaust by Loic Dauvillier, Greg Salsedo, and Marc Lizano, presents a hidden child graphic narrative from the point of view of a grandmother who survived the war and shares her history with her grandchild. Today, we can read dozen of stories of children who survived World War II because they were hidden by brave and kind people, and even more written by children who more recently saw their homelands destroyed by war while they watched helplessly and without understanding, as Zeina did.

Meanwhile, my stepdaughter makes just as much noise as she feels like making, and returns to her room and her apps, never twitching the curtain to peek outside unless she’s expecting a car in the driveway. She can go outside whenever she wants, but she rarely wants to, even as she hears Anne’s fervent, unrewarded desires.