THIRTEEN DOORWAYS, Wolves, and The Power of Place

I can’t get enough YA books set in Chicago. It’s where I grew up, and it’s always and forever the city of my heart, even if my only time spent living within the city limits was a short stint in college. I grew up in the south burbs, during the time when they were but cornfields, and at various times in my life have called Evanston and areas northwest of the city home.

Chicago is a city of neighborhoods. Neighborhoods that, when colonized from Natives including the Miami, Peoria, Potawatomi, and others, organized themselves around their similar immigrant communities. These communities and their ethnic heritage are proud and thriving, even today. It’s these tight-knit communities that fascinate me and which make me especially fond of Chicago-set YA books that are historical. Seeing how those enclaves add so much depth to the characters and story showcases research and passion for the setting in a way that depicts an authenticity and understanding of the power of place.

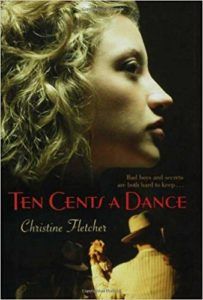

Christine Fletcher’s Ten Cents a Dance was the first book that introduced me to this idea in YA. Set in the Back of the Yards neighborhood in the 1940s, the story follows a young Ruby Jacinski, who is responsible for helping keep her family afloat. Her mother’s ill and things are made especially complicated for her because she is Polish. This is grounds for discrimination in the city, particularly for someone from her particular neighborhood. She’s able to get a job in the meat packing plants, but, that’s no where good for a 15-year-old girl.

Christine Fletcher’s Ten Cents a Dance was the first book that introduced me to this idea in YA. Set in the Back of the Yards neighborhood in the 1940s, the story follows a young Ruby Jacinski, who is responsible for helping keep her family afloat. Her mother’s ill and things are made especially complicated for her because she is Polish. This is grounds for discrimination in the city, particularly for someone from her particular neighborhood. She’s able to get a job in the meat packing plants, but, that’s no where good for a 15-year-old girl.

But through a chance meeting, Ruby’s given another opportunity. She’s introduced to the glitzy world of taxi dancing, where she learns the art of working her male patrons for gifts and money. Ethics are questionable, but the pay is something Ruby could never have imagined before. That’s why she does it—and also why she keeps it from her mother.

This book captures such a perfect historical moment, offering some necessary and powerful context to why Ruby needs this job and why it is people like her—white, for all intents and purposes—could be subject to discrimination, even with the skin color that equals power.

Thirteen Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All by Laura Ruby took me back to that reading experience, with a timely and timeless reminder about discrimination and the ways it reaches deep.

But first, an interlude.

I come from a divorced family, and I’ve been out of touch with my father for the majority of my life. This is by choice. Prior to marriage, though, I carried his last name. It’s unusual, unique, and exceptionally of a particular ethnic heritage. One need not do more than look at the letters and know a lot about my family’s background and where they came from.

It wasn’t, however, until I lived in Evanston that I learned where half of me came from.

I lived on the Northwestern University campus for a summer, in their un–air conditioned dorm rooms, while being a teaching assistant at a camp for gifted kids. The dorm room had no kitchen and no internet, so on top of being extremely hot, I had no way to feed myself except by ready-made items or going out and I had no entertainment except to read. There were just a handful of us living on campus in the spartan accommodations which we did, indeed, pay to stay in.

One night, one of the women invited a couple of us to her room for a traditional dinner from her culture. She was Muslim, and though I wish I could remember what else she told me about her heritage, I don’t remember much more than that. What I remember is this: she told me the story of mine, pulling history through my last name.

“You’re Sicilian. Like I am, partially. And look”—she pointed at her eye shape, the color of her hair, her ears and eyebrows— “you can see some of our traits written on our skin.”

She was, of course, right. A cursory internet search with the last name I had will not only show that my family came from Sicily, but that there are tours on the island of where they came from.

A year later, living in Chicago proper while taking a course on Chicago history at the Newbery Library, I stole away free pockets of time to peruse their subscription to Ancestry.com. Lo and behold: my father’s father’s family immigrated from Sicily and landed in Chicago.

Laura Ruby’s book is set in 1940s Chicago. This is the same era of Fletcher’s book, evoking some similar feelings of war fear, of poverty, of a world of working class meat packers and hard luck. But Frankie, the main character in Ruby’s book, isn’t Polish.

Laura Ruby’s book is set in 1940s Chicago. This is the same era of Fletcher’s book, evoking some similar feelings of war fear, of poverty, of a world of working class meat packers and hard luck. But Frankie, the main character in Ruby’s book, isn’t Polish.

Nor, as Kirkus’s Review incorrectly states, is she Italian.

Ruby is Sicilian, and her first words at the orphanage where she’s been sent to live are in Sicilian. Sicily, that little island off the coast of Italy, is where her family is from. And it’s not the same as Italy—not even a little bit.

Kirkus points this out because of their commitment to highlighting race in books. It’s important and laudable work, particularly as we know how literature favors stories of white people. How too often, people of color who get to be heroes in the story are often victims, struggling, or in positions of suffering or injustice.

Italy, in this case, codes white. This in and of itself isn’t incorrect (except the part where Frankie is Sicilian and not Italian), but it misses a load of important context. Sicily, as well as portions of southern Italy, in the cultural moment of this book, however, was not a place of power, prestige, or privilege, and immigrants from these regions experienced deplorable acts of discrimination.

Sicilian and southern Italian immigrants endured housing discrimination, police brutality, and a whole host of negative stereotypes leveraged against them in their every day lives, as well as in the media. They weren’t seen as “white” like their Nordic immigrant counterparts. Sicily, in particular, is a cultural hodgepodge, including a significant population from Greece and northern Africa. Peak Italian immigration population in Chicago hit in 1930, with the bulk of those coming from peasant classes in Sicily, Basilicata, and Campania.

In other words, about the time Frankie was born was the time immigration from Sicily hit its peak in Chicago.

It’s well documented and known that in today’s world, it’s people of color who experience loss of their homes and communities in cities. Gentrification, along with construction of highways, divides the spaces that were once theirs, further pushing them to the margins.

This was also the Sicilian experience in Chicago. The building of Cabrini-Green, along with various highways and interstates in the city, pushed Sicilian immigrants from their enclaves to the margins.

When I was younger and had little choice in the matter, I spent every other weekend with my father. After he and my mother divorced, he got remarried—to the woman he was cheating on my mother with. My stepmother was Polish, and her family was proud of that heritage. It was with them I first heard the antiquated ethnic slur used against (Southern) Italians and Sicilians: dago. It took me years to understand what it meant: people from these parts of the world were paid “as the day goes,” meaning that they took low-wage jobs, ones that weren’t seen as prestigious enough for other immigrant groups. Those same immigrants took jobs in factories that didn’t give them the opportunity to move up in social class until well after the second World War. (This same family called themselves the ethnic slur related to being from Poland, though it’s hard not to think about that name being used toward me when I was young and growing up without a lot of money because of the choices my father made).

Frankie, in Thirteen Doorways, takes a low-wage job when she’s kicked out of the orphanage and forced to live in a too-small apartment with an ever-growing family, comprised of a father who left her mother for another woman. It’s not glamorous, but it is something she does day after day in order to survive. It was here, especially, I saw my heritage and my own experiences unfold simultaneously. Frankie works because she has to. Frankie works because it’s an escape. But, like with the main character in Fletcher’s book, her options are exceptionally limited because of her ethnicity.

Pain can’t and shouldn’t be ranked. But pain seeps through Ruby’s book, both through Frankie and her situation, as well as that of Pearl, the ghost narrating the book. There’s the story of an interracial relationship here, as well as an interracial friendship, both of which are significant parts of Frankie and Pearl’s experiences. Both of which are exceptionally realistic to Chicago and its history, as well as the history of immigration to the city at this time. And, ultimately, Thirteen Doorways is about female pain and what it means to come up to every doorway and discover a wolf: a choice that’s not a choice, not really, all because you’re female in a society that does not allow real opportunities for you.

These same false doorways existed for Sicilians at this moment in time, in this place in time.

Ruby’s book ends with an author’s note about how this story was inspired by her mother-in-law, who casually dropped stories about her time in an orphanage in her youth. Casually, as in, that was a funny adventure. Not, necessarily, as we’ve come to see the orphan experience, particularly as it relates to this time period and how utterly poor and desperate families had to be to make such a choice for themselves. But this pain-turned-humor is also part of that Sicilian mentality—the dago spirit, if you will. The day will eventually go, as will you. You do what you can to make it so.

I don’t know a lot about my heritage, nor much about the wheres and hows of my father’s Sicilian family. I’ve dug into the archives, pulled out ancestral records. But Frankie’s story connected with mine deeply, in the way that those who have a shared history, even if it’s one that’s not necessarily well-known, can. I saw the wolves behind our doors because of being female, but I also saw the wolves behind our doors because we’ve got a Sicilian heritage. Because we both come from immigrants who sought out life in Chicago for better opportunities, even if it meant being discriminated against, physically and mentally abused, treated as little more than a scourge on the city.

The ways, too, that heritage became a point of pride and honor.

Sicily is part of Italy, but it’s not Italy. That’s what kept them separate, down, at this point in history.

But it’s this distinction that remains important even today, and wrapping up that experience under one clean description fails to capture the depth of that particular experience and reality at that particular time—as well as how it can, and does, resonate today with people who, like me, desperately seek a pin to connect to our own stories.