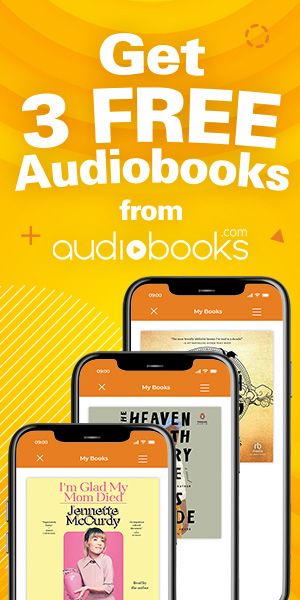

50 Must-Read Modern Classics in Translation

Did you know that only about 3% of books published in the U.S. each year are translations? The number varies from year to year, but regardless, it’s low. And yet reading literature from countries and languages other than one’s own has never been more important. Reading books in translation can offer us a different way of looking at the world. It can teach us about other cultures and their histories. It can help us understand ourselves better.

And it can also be fun. Missing out on translations is missing out on great art and great reading experiences. So below I’ve compiled a list of 50 must-read modern classics in translation. For the purposes of this post, I’ve defined a “modern classic” as a great book published within the last fifty years, so from 1968 on. My first pick has some stories from earlier than that date—and some from later—but otherwise, everything here was released in the last 50 years. The books are arranged by publication date, with the author’s country of origin noted as well. Book descriptions come from Goodreads.

Do you have a favorite book in translation I missed?

The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector, Translated by Katrina Dodson

The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector, Translated by Katrina Dodson

“Now, for the first time in English, are all the stories that made her a Brazilian legend: from teenagers coming into awareness of their sexual and artistic powers to humdrum housewives whose lives are shattered by unexpected epiphanies to old people who don’t know what to do with themselves.” (Brazil, 1960s–1970s)

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson, Translated by Thomas Teal

“In The Summer Book Tove Jansson distills the essence of the summer—its sunlight and storms—into twenty-two crystalline vignettes. This brief novel tells the story of Sophia, a six-year-old girl awakening to existence, and Sophia’s grandmother, nearing the end of hers, as they spend the summer on a tiny unspoiled island in the Gulf of Finland.” (Finland, 1972)

The Box Man by Kōbō Abe, Translated by E. Dale Saunders

“In this eerie and evocative masterpiece, the nameless protagonist gives up his identity and the trappings of a normal life to live in a large cardboard box he wears over his head.” (Japan, 1973)

Fatelessness by Imre Kertész, Translated by Tim Wilkinson

“At the age of 14 Georg Koves is plucked from his home in a Jewish section of Budapest and without any particular malice, placed on a train to Auschwitz. He does not understand the reason for his fate. He doesn’t particularly think of himself as Jewish. And his fellow prisoners, who decry his lack of Yiddish, keep telling him, ‘You are no Jew.’ In the lowest circle of the Holocaust, Georg remains an outsider.” (Hungary, 1973)

History by Elsa Morante, Translated by Lily Tuck

History by Elsa Morante, Translated by Lily Tuck

“History was written nearly thirty years after Elsa Morante and Alberto Moravia spent a year in hiding among remote farming villages in the mountains south of Rome. There she witnessed the full impact of the war and first formed the ambition to write an account of what history…does when it reaches the realm of ordinary people struggling for life and bread.” (Italy, 1974)

Terra Nostra by Carlos Fuentes, Translated by Margaret Sayers Peden

“[The novel] covers 20 centuries of European and American culture, and prominently features the construction of El Escorial by Philip II. The title is Latin for ‘Our earth.’ Modeled on James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, Terra Nostra shifts unpredictably between the sixteenth century and the twentieth, seeking the roots of contemporary Latin American society in the struggle between the conquistadors and indigenous Americans.” (Mexico, 1975)

Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, Translated by Michael Henry Heim

“Too Loud a Solitude is a tender and funny story of Hant’a—a man who has lived in a Czech police state—for 35 years, working as compactor of wastepaper and books. In the process of compacting, he has acquired an education so unwitting he can’t quite tell which of his thoughts are his own and which come from his books.” (Czechoslovakia, 1976)

Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter by Mario Vargas Llosa, Translated by Helen R. Lane

“Mario Vargas Llosa’s brilliant, multilayered novel is set in the Lima, Peru, of the author’s youth, where a young student named Marito is toiling away in the news department of a local radio station. His young life is disrupted by two arrivals.” (Peru, 1977)

If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler by Italo Calvino, Translated by William Weaver

“Italo Calvino’s novel is in one sense a comedy in which the two protagonists, the Reader and the Other Reader, ultimately end up married, having almost finished If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. In another, it is a tragedy, a reflection on the difficulties of writing and the solitary nature of reading.” (Italy, 1979)

So Long A Letter by Mariama Bâ, Translated by Modupé Bodé-Thomas

So Long A Letter by Mariama Bâ, Translated by Modupé Bodé-Thomas

“The brief narrative, written as an extended letter, is a sequence of reminiscences—some wistful, some bitter—recounted by recently widowed Senegalese schoolteacher Ramatoulaye Fall. Addressed to a lifelong friend, Aissatiou, it is a record of Ramatoulaye’s emotional struggle for survival after her husband betrayed their marriage by taking a second wife.” (Senegal, 1979)

The name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, Translated by William Weaver

“The year is 1327. Franciscans in a wealthy Italian abbey are suspected of heresy, and Brother William of Baskerville arrives to investigate. When his delicate mission is suddenly overshadowed by seven bizarre deaths, Brother William turns detective.” (Italy, 1980)

The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende, Translated by Magda Bogin

“Here is patriarch Esteban, whose wild desires and political machinations are tempered only by his love for his ethereal wife, Clara, a woman touched by an otherworldly hand. Their daughter, Blanca, whose forbidden love for a man Esteban has deemed unworthy infuriates her father, yet will produce his greatest joy: his granddaughter Alba.” (Chile, 1982)

The Post-Office Girl by Stefan Zweig, Translated by Joel Rotenberg

“The logic of capitalism, boom and bust, is unremitting and unforgiving. But what happens to human feeling in a completely commodified world? In The Post-Office Girl, Stefan Zweig, a deep analyst of the human passions, lays bare the private life of capitalism.” (Austria, 1982)

The Piano Teacher by Elfriede Jelinek, Translated by Joachim Neugroschel

The Piano Teacher by Elfriede Jelinek, Translated by Joachim Neugroschel

“Erika Kohut is a piano teacher at the prestigious and formal Vienna Conservatory, who still lives with her domineering and possessive mother. Her life appears to be a seamless tissue of boredom, but Erika, a quiet thirty-eight-year-old, secretly visits Turkish peep shows at night to watch live sex shows and sadomasochistic films.” (Austria, 1983)

The City and the House by Natalia Ginzburg, Translated by Dick Davis

“This powerful novel is set against the background of Italy from 1939 to 1944, from the anxious months before the country entered the war, through the war years, to the Allied victory with its trailing wake of anxiety, disappointment, and grief.” (Italy, 1984)

The Lover by Marguerite Duras, Translated by Barbara Bray

“Set in the prewar Indochina of Marguerite Duras’s childhood, this is the haunting tale of a tumultuous affair between an adolescent French girl and her Chinese lover. In spare yet luminous prose, Duras evokes life on the margins of Saigon in the waning days of France’s colonial empire.” (France, 1984)

The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera, Translated by michael Henry Heim

“In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera tells the story of a young woman in love with a man torn between his love for her and his incorrigible womanizing and one of his mistresses and her humbly faithful lover.” (Czechoslovakia, 1984)

Fantasia: An Algerian Cavalcade by Assia Djebar, Translated by Dorothy S. Blair

“Assia Djebar intertwines the history of her native Algeria with episodes from the life of a young girl in a story stretching from the French conquest in 1830 to the War of Liberation of the 1950s. The girl, growing up in the old Roman coastal town of Cherchel, sees her life in contrast to that of a neighboring French family, and yearns for more than law and tradition allow her to experience.” (Algeria, 1985)

Love in the time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez, Translated by Edith Grossman

Love in the time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez, Translated by Edith Grossman

“In their youth, Florentino Ariza and Fermina Daza fall passionately in love. When Fermina eventually chooses to marry a wealthy, well-born doctor, Florentino is devastated, but he is a romantic. As he rises in his business career he whiles away the years in 622 affairs—yet he reserves his heart for Fermina.” (Colombia, 1985)

The Sand Child by Tahar Ben Jelloun, Translated by Alan Sheridan

“In this lyrical, hallucinatory novel set in Morocco, Tahar Ben Jelloun offers an imaginative and radical critique of contemporary Arab social customs and Islamic law. The Sand Child tells the story of a Moroccan father’s effort to thwart the consequences of Islam’s inheritance laws regarding female offspring.” (Morocco, 1985)

Death in Spring by Mercé Rodoreda, Translated by Martha Tennent

“The novel tells the story of the bizarre and destructive customs of a nameless town—burying the dead in trees after filling their mouths with cement to prevent their soul from escaping, or sending a man to swim in the river that courses underneath the town to discover if they will be washed away by a flood—through the eyes of a fourteen-year-old boy who must come to terms with the rhyme and reason of this ritual violence.” (Spain, 1986)

The Door by Magda Szabó, Translated by Len Rix

“A busy young writer struggling to cope with domestic chores, hires a housekeeper recommended by a friend. The housekeeper’s reputation is one built on dependable efficiency, though she is something of an oddity. Stubborn, foul-mouthed and with a flagrant disregard for her employer’s opinions she may even be crazy.” (Hungary, 1987)

Before by Carmen Boullosa, Translated by Peter Bush

“Part bildungsroman, part ghost story, part revenge novel, Before tells the story of a woman who returns to the landscape of her childhood to overcome the fear that held her captive as a girl.” (Mexico, 1989)

LIke Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel, Translated by Thomas Christensen and CArol Christensen

LIke Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel, Translated by Thomas Christensen and CArol Christensen

“A sumptuous feast of a novel, it relates the bizarre history of the all-female De La Garza family. Tita, the youngest daughter of the house, has been forbidden to marry, condemned by Mexican tradition to look after her mother until she dies. But Tita falls in love with Pedro, and he is seduced by the magical food she cooks.” (Mexico, 1989)

A Quiet Life by Kenzaburō Ōe, Translated by Kunioki Yanagishita William Wetherall

“A Quiet Life is narrated by Ma-chan, a twenty-year-old woman. Her father is a famous and fascinating novelist; her older brother, though severely brain damaged, possesses an almost magical gift for musical composition; and her mother’s life is devoted to the care of them both.” (Japan, 1990)

A Heart So White by Javier Marias, Translated by Margaret Jull Costa

“Javier Marías’s A Heart So White chronicles with unnerving insistence the relentless power of the past. Juan knows little of the interior life of his father Ranz; but when Juan marries, he begins to consider the past anew, and begins to ponder what he doesn’t really want to know.” (Spain, 1992)

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami, Translated by Jay Rubin

“In a Tokyo suburb a young man named Toru Okada searches for his wife’s missing cat. Soon he finds himself looking for his wife as well in a netherworld that lies beneath the placid surface of Tokyo.” (Japan, 1994)

Blindness by José Saramago, Translated by Giovanni POntiero

Blindness by José Saramago, Translated by Giovanni POntiero

“A city is hit by an epidemic of ‘white blindness’ that spares no one. Authorities confine the blind to an empty mental hospital, but there the criminal element holds everyone captive, stealing food rations and assaulting women. There is one eyewitness to this nightmare who guides her charges…through the barren streets, and their procession becomes as uncanny as the surroundings are harrowing.” (Portugal, 1995)

The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald, Translated by Michael Hulse

“The Rings of Saturn is his record of these travels, a phantasmagoria of fragments and memories, fraught with dizzying knowledge and desperation and shadowed by mortality. As in The Emigrants, past and present intermingle: the living come to seem like supernatural apparitions while the dead are vividly present.” (Germany, 1995)

Voices from Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexievich, Translated by Keith Gessen

“On April 26, 1986, the worst nuclear reactor accident in history occurred in Chernobyl and contaminated as much as three quarters of Europe. Voices from Chernobyl is the first book to present personal accounts of the tragedy. Journalist Svetlana Alexievich interviewed hundreds of people affected by the meltdown…and their stories reveal the fear, anger, and uncertainty with which they still live.” (Belarus, 1997)

The Savage Detectives by Robert Bolaño, Translated by Natasha Wimmer

“New Year’s Eve, 1975: Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima, founders of the visceral realist movement in poetry, leave Mexico City in a borrowed white Impala. Their quest: to track down the obscure, vanished poet Cesárea Tinajero. A violent showdown in the Sonora desert turns search to flight; twenty years later Belano and Lima are still on the run.” (Chile, 1998)

Delirium by Laura Restrepo, Translated by Natasha Wimmer

“In this remarkably nuanced novel, both a gripping detective story and a passionate, devastating tale of eros and insanity in Colombia, internationally acclaimed author Laura Restrepo delves into the minds of four characters.” (Colombia, 2000)

An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter by César Aira, Translated by Chris Andrews

“An astounding novel from Argentina that is a meditation on the beautiful and the grotesque in nature, the art of landscape painting, and one experience in a man’s life that became a lightning rod for inspiration.” (Argentina, 2000)

The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón, Translated by Lucia Graves

The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón, Translated by Lucia Graves

“The international literary sensation, about a boy’s quest through the secrets and shadows of postwar Barcelona for a mysterious author whose book has proved as dangerous to own as it is impossible to forget.” (Spain, 2001)

Snow by Orhan Pamuk, Translated by Maureen Freely

“Following years of lonely political exile in Western Europe, Ka, a middle-aged poet, returns to Istanbul to attend his mother’s funeral. Only partly recognizing this place of his cultured, middle-class youth, he is even more disoriented by news of strange events in the wider country: a wave of suicides among girls forbidden to wear their head scarves at school.” (Turkey, 2002)

A Tale of Love and Darkness by Amos Oz, Translated by Nicholas de Lange

“A family saga and a magical self-portrait of a writer who witnessed the birth of a nation and lived through its turbulent history. A Tale of Love and Darkness is the story of a boy who grows up in war-torn Jerusalem, in a small apartment crowded with books in twelve languages and relatives speaking nearly as many.” (Israel, 2002)

The Yacoubian Building by Alaa Al Aswany, Translated by Humphrey Davies

“All manner of flawed and fragile humanity reside in the Yacoubian Building…a fading aristocrat and self-proclaimed ‘scientist of women’; a sultry, voluptuous siren; a devout young student, feeling the irresistible pull toward fundamentalism; a newspaper editor helplessly in love with a policeman; a corrupt and corpulent politician, twisting the Koran to justify his desires.” (Egypt, 2002)

The Housekeeper and the Professor by Yoko Ogawa, Translated by Stephen Snyder

The Housekeeper and the Professor by Yoko Ogawa, Translated by Stephen Snyder

“He is a brilliant math Professor with a peculiar problem—ever since a traumatic head injury, he has lived with only eighty minutes of short-term memory. She is an astute young Housekeeper, with a ten-year-old son, who is hired to care for him. And every morning, as the Professor and the Housekeeper are introduced to each other anew, a strange and beautiful relationship blossoms between them.” (Japan, 2003)

The Ministry of Pain by Dubravka Ugrešić, Translated by Michael Henry Heim

“Abandoning literature, Tanja encourages her students to indulge their ‘Yugonostalgia’ in essays about their personal experiences during their homeland’s cultural and physical disintegration. But Tanja’s act of academic rebellion incites the rage of one renegade member of her class—and pulls her dangerously close to another—which, in turn, exacerbates the tensions of a life in exile that has now begun to spiral seriously out of control.” (Yugoslavia, Netherlands, 2004)

Broken Glass by Alain Mabanckou, Translated by Helen Stevenson

“Alain Mabanckou’s riotous new novel centers on the patrons of a run-down bar in the Congo. In a country that appears to have forgotten the importance of remembering, a former schoolteacher and bar regular nicknamed Broken Glass has been elected to record their stories for posterity. But Broken Glass fails spectacularly at staying out of trouble.” (Republic of the Congo, 2005)

The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery, Translated by Alison Anderson

“We are in the center of Paris, in an elegant apartment building inhabited by bourgeois families. Renée, the concierge, is witness to the lavish but vacuous lives of her numerous employers. Outwardly she conforms to every stereotype of the concierge: fat, cantankerous, addicted to television. Yet, unbeknownst to her employers, Renée is a cultured autodidact who adores art, philosophy, music, and Japanese culture.” (France, 2006)

The Proof of the Honey by Salwa Al Neimi, Translated by Cal Perkins

“The Proof of the Honey is a superb celebration of female pleasure. A Syrian scholar working in Paris is invited to contribute to a conference on the subject of classic erotic literature in Arabic. The invitation provides occasion for her to evoke memories from her own life, to exult in her personal liberty, her lovers, her desires, and to revisit moments of shared intimacy with other women as they discuss life, love, and sexual desire.” (Syria, 2007)

The Vegetarian by Han Kang, Translated by Deborah Smith

“Before the nightmare, Yeong-hye and her husband lived an ordinary life. But when splintering, blood-soaked images start haunting her thoughts, Yeong-hye decides to purge her mind and renounce eating meat. In a country where societal mores are strictly obeyed, Yeong-hye’s decision to embrace a more ‘plant-like’ existence is a shocking act of subversion.” (South Korea, 2007)

To the End of the Land by David Grossman, Translated by Jessica Cohen

To the End of the Land by David Grossman, Translated by Jessica Cohen

“Ora, a middle-aged Israeli mother, is on the verge of celebrating her son Ofer’s release from army service when he returns to the front for a major offensive. In a fit of preemptive grief and magical thinking, she sets out for a hike in the Galilee, leaving no forwarding information for the ‘notifiers’ who might darken her door with the worst possible news.” (Israel, 2008)

The Hunger Angel by Herta Müller, Translated by Philip Boehm

“It was an icy morning in January 1945 when the patrol came for seventeen-year-old Leo Auberg to deport him to a camp in the Soviet Union. Leo would spend the next five years in a coke processing plant, shoveling coal, lugging bricks, mixing mortar, and battling the relentless calculus of hunger that governed the labor colony: one shovel load of coal is worth one gram of bread.” (Romania, Germany, 2009)

My Struggle: Book One by Karl Ove Knausgård, Translated by Don Bartlett

“Almost ten years have passed since Karl O. Knausgaard’s father drank himself to death. He is now embarking on his third novel while haunted by self-doubt. Knausgaard breaks his own life story down to its elementary particles, often recreating memories in real time, blending recollections of images and conversation with profound questions in a remarkable way.” (Norway, 2009)

Three Strong Women by Marie NDiaye, Translated by John Fletcher

“This is the story of three women who say no: Norah, a French-born lawyer who finds herself in Senegal, summoned by her estranged, tyrannical father to save another victim of his paternity; Fanta, who leaves a modest but contented life as a teacher in Dakar to follow her white boyfriend back to France, where his delusional depression and sense of failure poison everything; and Khady, a penniless widow put out by her husband’s family with nothing but the name of a distant cousin” (France, 2009)

Touch by Adania Shibli, Translated by Paula Haydar

“Touch centers on a girl, the youngest of nine sisters in a Palestinian family. In the singular world of this novella, this young woman’s everyday experiences resonate until they have become as weighty as any national tragedy.” (Palestine, 2010)

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante, Translated by Ann Goldstein

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante, Translated by Ann Goldstein

“My Brilliant Friend is a rich, intense and generous hearted story about two friends, Elena and Lila. Ferrante’s inimitable style lends itself perfectly to a meticulous portrait of these two women that is also the story of a nation and a touching meditation on the nature of friendship.” (Italy, 2011)

The Last Lover by Can Xue, Translated by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen

“In Can Xue’s extraordinary book, we encounter a full assemblage of husbands, wives, and lovers. Entwined in complicated, often tortuous relationships, these characters step into each other’s fantasies, carrying on conversations that are ‘forever guessing games.’ Their journeys reveal the deepest realms of human desire.” (China, 2014)

Want even more translation in your life? Check out this list of 100 must-read classics in translation—books from 50 up to thousands of years ago.